Hmar language

The Hmar language (Hmar: Khawsak Țawng) is a Northern Mizo language spoken by the Hmar people of Northeast India. It belongs to the Kuki-Chin branch of this language family. Speakers of Hmar often use Mizo(Duhlian) as their second language (L2).[1][2] The language has official status in some regions and is used in education to varying degrees. It possesses a rich oral tradition, including traditional sayings (Ṭawngkasuok) and festival songs like the Sikpui Hla.

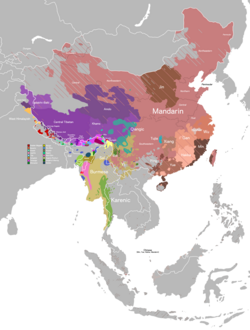

ClassificationThe Hmar language is a member of the Tibeto-Burman language family. It is specifically classified under the Zohnahtlak languages group.[8][10] The Zohnahtlak languages, including Hmar, are spoken in Mizoram, neighboring areas of Northeast India, and also in adjacent countries like Bangladesh and Myanmar.[8] The language is verb-final.[10] According to VanBik's (2007) classification of Kuki-Chin languages, Hmar is placed within the 'Central' branch.[8] This branch also includes languages like Mizo and Lai. For context, Kuki-Chin languages are broadly divided by VanBik into Central, Peripheral (Northern and Southern), and Maraic branches. Another grouping, often termed 'Northwestern Kuki-Chin' or historically 'Old Kuki' (including languages like Aimol, Anal, Kom), is also recognized and is characterized by lacking some typical features of the core Kuki-Chin group, such as verb stem alternations.[8] The broader classification of Tibeto-Burman (often referred to as Sino-Tibetan) is a subject of ongoing scholarly discussion. Some researchers, like Blench and Post (2013), propose the term Trans-Himalayan for the phylum to better reflect the geographical distribution and diversity of these languages, particularly highlighting the numerous languages in Northeast India that may represent independent branches and challenge traditional binary classifications that privilege Sinitic or well-known literary languages like Tibetan and Burmese.[11] These scholars emphasize the complexity arising from extensive language contact and the need to give equal weight to lesser-documented languages in phylogenetic considerations.[11] Hmar, like many languages in the region, is considered to be in a developing stage and requires further standardization in several linguistic areas.[10] Geographical distributionRegions and speaker numbersThe Hmar people are dispersed across several states in Northeast India, primarily Mizoram, Manipur, Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura, with significant populations often concentrated in the border regions between these states.[12] Diaspora communities also exist in Myanmar and Bangladesh (among the Bawm people tribe).[12] The Khawsak dialect of Hmar is spoken in locations including:

Population Estimates: According to the Census of India, 2001, there were approximately 83,400 Hmar speakers.[12] The total ethnic Hmar population is estimated to be higher, possibly between 200,000 and 300,000, though this is a general estimate due to factors such as their wide dispersion, the historical classification of some Hmar clans as separate tribes, and variations in census operations.[12] In Mizoram, the 2001 census recorded the Hmar population at 18,155. This figure might not include all ethnic Hmars, particularly those who may not speak the Hmar language as their primary mother tongue.[12] The 2011 Census of India recorded 98,988 speakers of Hmar as a mother tongue.[7] The significant dispersion of Hmar speakers may contribute to slight dialectal distinctions across different regions. DialectsIn Manipur, Hmar exhibits partial mutual intelligibility with the other Kukish dialects of the area including Thadou, Paite, Aimol, Vaiphei, Simte, Kom and Gangte languages.[13] The Hmar language, as it is recognized today, was previously known as the Khawsak dialect.[14] This dialect was accepted by the various Hmar groups as a common language for literary and teaching purposes, although other Hmar languages and dialects continue to be widely spoken.[10] HistoryThe Hmar people were first recognized as a distinct tribal community in the North-Eastern States of India. Prior to official recognition, they were often grouped under the term 'Kuki' or 'Old Kuki,' a label applied by outsiders to various hill tribes in the region.[10] The Government of India officially recognized the Hmar tribe by including it in the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Lists (Modification) Order, 1956 (Ministry of Home Affairs Order No. S.R.O. 2477, dated 29 October 1956).[10] This allowed different tribes, including the Hmar, to be known by their specific names rather than generic terms.[10] The Hmar people are recognized as an indigenous tribal group in Northeast India.[12] They are officially recognized as a Scheduled Tribe by the Indian constitution since 1951.[12] Early documentationThe Hmar language was first documented in written form in the early 20th century by George Abraham Grierson in his extensive Linguistic Survey of India.[10] Origins and early settlementOral traditions and historical accounts suggest the Hmar were among the earliest settlers in the region that is now the state of Mizoram. This is supported by the Hmar names of many villages and rivers, particularly in the Champhai area bordering Myanmar.[12] Over time, with the arrival of other related groups, the Hmar population spread to other parts of Northeast India.[12] Sinlung: Traditional place of originHmar tradition consistently refers to Sinlung as their ancestral homeland. Numerous songs and folktales recount their time in Sinlung and their subsequent migration.[15] The exact location of Sinlung is a subject of scholarly debate, with several theories proposed:

Reasons for leaving Sinlung are also varied in oral traditions, including the search for fertile land or escape from oppressive rulers.[15] One Hmar song evocatively states:

(From Sinlung / I jumped out like a Mithun from its captivity (Bison); / Innumerable were the encounters, / With the children of men.)[15] This suggests a departure involving overcoming obstacles and facing numerous encounters during their migration. It is believed the Hmars were part of larger waves of migration from China southwards, possibly forced out by the Ch'in Dynasty, eventually moving into Southeast Asia and then India.[15] Socio-political awakeningThe introduction of modern elementary education by Christian missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries played a significant role in awakening the socio-economic, cultural, and political consciousness of the Hmar people.[12] During the period leading up to Indian Independence and in the decades that followed, various political movements emerged in the Lushai Hills (now Mizoram). Initially, many Hmars supported broader Mizo ethnic consolidation movements.[12] Hmar political movements and organizationsDiscontent grew among the Hmars due to the perceived neglect of their specific concerns and aspirations within larger Mizo political formations, especially after the creation of Mizoram state.[12] This led to the formation of distinct Hmar political organizations.

Resentment increased due to the exclusion of some Hmar-inhabited areas from the newly formed Mizoram state and what Hmar activists described as discriminatory policies and neglect by the Mizoram government towards Hmar areas within the state. They cited lack of access to basic amenities and alleged policies of forced assimilation and Mizo chauvinism.[12]

Period of conflict and the Sinlung Hills Development Council (SHDC)Tensions escalated, leading to protests and state responses. An HPC-organized bandh (general strike) in March 1989 was met with police action.[12] This period saw the formation of the Hmar Volunteer Cell (HVC), an armed wing of the HPC, leading to armed confrontations with state forces between 1989 and 1992.[12] Negotiations between the HPC and the Government of Mizoram resulted in the signing of a Memorandum of Settlement (MoS) on July 27, 1994. This led to the surrender of HPC armed cadres.[12] The MoS aimed to grant autonomy for social, economic, cultural, and educational advancement through the creation of the Sinlung Hills Development Council (SHDC), but it was not granted political autonomy.[12] The SHDC was officially formed on August 27, 1997, covering areas with a Hmar majority population. However, disagreements over its exact demarcation and the failure to introduce Hmar as a medium of instruction in SHDC areas, coupled with alleged political interference and limited funding, rendered the council largely defunct over time.[12] Some HPC leaders and cadres rejected the 1994 MoS and formed the HPC (Democratic), continuing an armed movement for autonomy.[12] Various attempts at peace talks and Suspension of Operation (SoO) agreements occurred, notably in 2010, but faced challenges and did not lead to a lasting resolution at that time.[12] The HPC(D) demanded a Hmar Territorial Council (HTC) within Mizoram under the Indian Constitution.[12] The Hmar political movement, as articulated by its proponents, has generally aimed to preserve Hmar identity, culture, and language and ensure their socio-economic development within the framework of the Indian constitution and often in concert with broader Mizo ethnic solidarity, rather than seeking to break away from Mizoram.[12] PhonologyConsonantsVowelsTonesAlphabet (Hmar Hawrawp) and OrthographyThe Hmar alphabets, known as Hmar Hawrawp, has 25 letters: 6 vowels and 19 consonants.[16][10] It is a modified version of the Roman script with some diacritic marks to help pronounce the dialect.[17]

Pronunciation

GrammarThe Hmar language exhibits several notable grammatical features, common to many Tibeto-Burman languages, but also with unique characteristics. It is an agglutinative language.[18] AgreementHmar demonstrates a rich agreement system. Agreement markers, often in the form of pronominal clitics, can appear on verbs and adjectives, indicating features like person and number of arguments (subject, object).[18] Unlike many Indo-Aryan languages where the presence of a lexical case marker (postposition) often blocks agreement, in Hmar, the presence or absence of a postposition generally does not affect agreement.[18] However, there are instances, particularly in relative clauses and passives, where the ergative case marker and the agreement marker are mutually dependent, meaning either both appear or both are absent.[18] Predicate adjectives in Hmar also exhibit agreement with the noun they modify, carrying person and number agreement features that are homophonous with those found on verbs. Hmar does not have gender agreement.[18] Pronominal cliticsHmar utilizes pronominal clitics that attach to verbs. These clitics can represent subjects, direct objects, indirect objects, and possessors.[18] For example, the object agreement markers for the first person singular is -mi and for the second person singular is -ce. The third-person singular subject agreement marker is typically -a.[18] These clitics are crucial for understanding the relationships between participants in a sentence, especially when overt pronouns are dropped (see Pro-drop language). ErgativityHmar exhibits a split ergativity system based on person. This means that the language uses ergative case marking for some noun phrases (typically third person) and accusative case marking for others (typically first and second person).[18] When a subject is marked with the ergative case (e.g., -n), it often triggers corresponding agreement on the verb. The interplay between ergative marking and agreement is a significant feature of Hmar syntax.[18] Adposition incorporationA distinctive feature of Hmar grammar is adposition incorporation. This is a process where an adposition (typically a postposition, like le meaning "with") moves from its position with a noun phrase and incorporates into the verb, often changing its form (e.g., le becomes -pui when attached to a verb).[18] This incorporation can have a transitivizing effect on intransitive verbs. When an adposition is incorporated, the verb it attaches to may then take an ergative subject and an object agreement clitic, indicating an increase in the verb's valency.[18] This phenomenon is not commonly found in other language families of the Indian subcontinent.[18] Long-distance agreementHmar also features long-distance agreement, where an argument in an embedded clause can trigger agreement on the predicate (verb or adjective) of the main or higher clause.[18] This is particularly evident in constructions involving subject-to-subject raising and Exceptional Case Marking (ECM). In ECM constructions, the pronominal agreement marker of the embedded subject can appear as a clitic on the matrix verb.[18] Pronominal strength hierarchyIn sentences with conjoined pronominal subjects, Hmar follows a pronominal strength hierarchy for agreement. The first-person subject is considered "stronger" than second- or third-person subjects, and a second-person subject is "stronger" than a third-person subject.[18] This means that if a first-person pronoun is conjoined with a third-person pronoun, the verb will show first-person plural agreement, even if the first-person pronoun itself is null (pro-dropped) and only recoverable from the verbal agreement. The hierarchy is typically: 1st person > 2nd person > 3rd person.[18] MorphologyHmar morphology is characterized by agglutination, particularly in its verb system. This involves the use of prefixes and suffixes to derive various grammatical forms, including causatives. CausativizationHmar employs both morphological and lexical strategies for forming causative verbs.[14] Morphological causativesTwo primary morphological causative affixes are productively used:

Lexical causativesLexical causatives are less common and unproductive in Hmar. They include:[14]

Verb stem alternationHmar, like other Kuki-Chin languages, exhibits verb stem alternation (Stem I and Stem II forms).[14][8] General Kuki-Chin characteristics of verb stem alternation include Stem I forms often being associated with main clauses or intransitive predicates and usually having an open syllable, while Stem II forms are often associated with subordinated clauses or transitive predicates and often have a closed syllable (e.g., Hakha Lai tsòo ‘buy.1’ and tsook ‘buy.2’).[8] In Hmar causative constructions, both Stem I and Stem II verbs can generally occur with causative morphology.[14] For example, with the root 'eat' (Stem I: fà, Stem II: fàk), both ìn-fà-tìr and ìn-fàk-tìr ('cause to eat') are possible. While `/ìn-...-tìr/` can occur with Stem I, it is more commonly associated with Stem II forms. The `/sùk-/` causative can also combine with both stems.[14] Interaction with reflexive/reciprocal markersThe verbal reflexive/reciprocal prefix `/ìn-/` (which can reduce to `n-` after a vowel with singular subjects) is crucial in causative constructions.[14]

Double causativesHmar allows for the formation of double causatives, expressing the meaning 'X CAUSES Y to CAUSE Z'. This can be achieved in two ways:[14]

Isomorphism of possessive prefixes and agreement procliticsA notable feature of Kuki-Chin languages, including Hmar, is the isomorphism (similarity in form) between nominal possessive prefixes and verbal subject agreement proclitics.[8] This suggests a historical link or shared morphological origin for markers of possession on nouns and subject agreement on verbs. SyntaxPronounsVerbsNounsCase systemBeyond ergativity, Hmar employs a system of case marking to indicate the grammatical functions of nouns within a sentence. While the nominative case marker is often null, other cases such as dative and locative are marked by postpositions.[18] The interaction between case marking and agreement is a key aspect of Hmar grammar. VocabularyWriting SystemThe Hmar language uses a Roman script-based alphabet consisting of 25 letters, as detailed in the "Phonology" section.[10] The Khawsak dialect has been adopted as the common standard for literary purposes and language teaching among the various Hmar groups.[10] Early literature and publicationsEarly efforts in Hmar literature were significantly driven by religious purposes and the desire for literacy in the native language.[10]

Since the mid-20th century, a more substantial number of books have been published, contributing to the development of Hmar as a Modern Indian Language (MIL).[10] Official Status and UsageHmar has been recognized as a language for educational purposes and as a Modern Indian Language (MIL) in several states in Northeast India. Manipur

Textbooks developed in Manipur, such as "Readers," have also been adopted by some vernacular schools in Cachar, Assam, for upper primary schooling.[10] Assam

New textbooks had to be written for all these levels according to the norms laid down by the respective educational authorities.[10] Mizoram and MeghalayaIn both Mizoram and Meghalaya, the Hmar tribe is recognized as a Scheduled Tribe (Hills).[10] There have been efforts to introduce the teaching of Hmar language at the primary level in these states, though significant progress had not been reported by the time of V.L. Bapui's 2017 article.[10] The earlier statement "Hmar is a recognised language in the School curriculum of Assam, Manipur and Mizoram..." requires nuance based on this source, particularly for Mizoram where introduction at primary level was still an ongoing effort. Preservation EffortsThe Hmar language is considered endangered due to decreasing transmission among younger generations and the increasing influence of dominant regional languages such as Mizo, Manipuri, Assamese, and Bengali.[status 1] Formal institutional support for Hmar language preservation is limited; however, grassroots efforts have emerged in recent years. Online communities on platforms such as WhatsApp and Facebook serve as important spaces where speakers and learners share resources, discuss grammar, and encourage the use of Hmar in daily communication.[status 2] These digital groups play a vital role in sustaining interest and usage of the language, especially among younger members of the community. The Hmar language is recognized in the school curricula of some regions and has been acknowledged as one of the Modern Indian Languages at Manipur University.[status 3] However, the extent of educational support varies across different areas. Linguists and community members emphasize the importance of documenting the language, developing educational materials, and raising awareness to help preserve Hmar and maintain the cultural identity of its speakers.[status 4] Challenges in language educationDespite progress in achieving recognition for Hmar in education, several challenges persist:

These challenges underscore the need for continued institutional and community efforts to ensure the vitality and transmission of the Hmar language through the education system. Cultural SignificanceṬawngkasuokṬawngkasuok (Anglicized: Trong-ka-sook) are traditional sayings or adages of the Hmar people, deeply embedded in their culture and serving as repositories of wisdom and guidance.[19] The term is a Hmar compound word: ṭawng meaning 'language' or 'dialect', ka meaning 'mouth', and suok meaning 'out of'. Thus, it literally translates to "language spoken out of the mouth."[19] The initial letter 'Ṭ' is a retroflex stop, pronounced with the tongue against the roof of the mouth, similar to a 'tr' sound as in 'tree'.[19] Hmar people use Ṭawngkasuok in conversations to offer advice, emphasize a point, or impart traditional wisdom, particularly to younger generations.[19] Below are some examples of Ṭawngkasuok:

* **Contextual Translation:** "Sometimes the north-tree flowers, at other times, the south-tree."[19] * **Explanation:** This saying conveys that everyone will have their chance to succeed or shine; if not today, their time will come. It encourages perseverance and patience. The "north-tree" and "south-tree" are metaphorical, suggesting that success is not limited by direction or current circumstances.[19]

* **Contextual Translation:** "Words once spoken are like spilled water, irretrievable once released."[19] * **Explanation:** This adage advises caution in speech, emphasizing that words, once uttered, cannot be taken back, much like spilled water. It highlights the lasting consequences of one's words. The rhyming of ṭawng inbuo (words spilled) and tui inbuo (water spilled) adds to its poetic quality.[19]

* **Contextual Translation:** "A king who was never a king before is noxious (bitter)."[19] * **Explanation:** This saying suggests that individuals unaccustomed to power may misuse it when suddenly given authority, becoming cruel or corrupt. It can also generally refer to someone who, upon gaining wealth or status they never had, becomes extravagant or spoiled.[19]

* **Contextual Translation:** "A fly sits nowhere but on an infected skin."[19] * **Explanation:** This metaphor implies that if rumors or negative things are said about someone or something, there is likely some truth to it, at least in part. It is similar to the English saying, "Where there is smoke, there is fire."[19]

* **Contextual Translation:** "A knee cannot rise to/surpass the stature/level of a head."[19] * **Explanation:** While literally true, this Ṭawngkasuok symbolizes the importance of seniority and experience. It suggests that younger individuals cannot easily attain the wisdom or standing of their elders.[19]

* **Contextual Translation:** "A lioness cannot conceal her true character."[19] * **Explanation:** Similar to idioms like "a tiger never changes his stripes," this saying means that a person's fundamental nature or ingrained traits will eventually reveal themselves, despite attempts to hide or change them.[19]

* **Contextual Translation:** "Hard work is good in all aspects, except the toll it takes on one’s waist."[19] * **Explanation:** This adage praises diligence, highly valued in Hmar culture. It suggests that hard work brings many benefits (like better food and respect), with physical strain being its only downside.[19]

* **Contextual Translation:** "The machete seller and the gong seller cross paths."[19] * **Explanation:** This saying describes a situation where two individuals with contrasting or complementary needs or desires meet. Historically, it was used to describe a hastily married couple, symbolizing the coming together of two people with different wants that the other could fulfill. It doesn't imply superiority of one item (machete or gong) over the other.[19]

* **Contextual Translation:** "If one works lazily, he eats taro leaves; if he works hard, he eats marak (firm rice)."[19] * **Explanation:** This saying emphasizes the rewards of diligence. Taro leaves represent modest food, while marak (a cherished firm rice, also known as buchangrum) symbolizes a better reward for hard work. The saying has a poetic quality due to internal rhymes.[19]

* **Contextual Translation:** "Do not wake a sleeping wildcat." (or leopard)[19] * **Explanation:** This is a warning against provoking unnecessary danger or trouble, similar to "Let sleeping dogs lie." It advises against challenging someone who is currently calm but could be dangerous if provoked.[19]

* **Contextual Translation:** "No other fruit grows on the gooseberry tree."[19] * **Explanation:** This adage points to the resemblance in character or behavior between parents and their children, often used in a negative context. For instance, if a child of a known thief is caught stealing, this saying might be invoked.[19]

* **Contextual Translation:** "Sweet words win a prized gayal (mithun)."[19] * **Explanation:** This metaphor signifies that respectful and kind language can win hearts or achieve difficult objectives. The siel (mithun) is a highly valued animal in Hmar culture.[19] These sayings reflect the Hmar people's values, including a strong work ethic, respect for elders, caution in speech, and resilience.[19] Sikpui Ruoi (Great Winter Festival) and its Hla (Song)Among the many festivals of the Hmar people, Sikpui Ruoi (meaning Sik = winter, Pui = Great, Ruoi = Feast/Festival) is considered the most significant.[15] It is a festival celebrated since ancient times, marking a period of abundance when the previous year's harvest is still plentiful even as the new harvest season begins. Such a year is termed fapang ralinsan.[15] Origin and celebrationThe exact origin of Sikpui Ruoi is debated, with theories suggesting it began:

Preparations for Sikpui Ruoi begin months in advance, with young men and women winnowing the previous year's rice, which is then distributed among households for brewing Zu (rice beer).[15] The festival typically lasts for seven days, though it can extend longer. During the celebration, families bring their Zu to a common venue to share, feast, and make merry.[15] Sikpui Ruoi is primarily a celebration of nature's bounty and the community's symbiotic relationship with it. It is a highly inclusive festival where social distinctions of wealth or status are minimized, and the rich are encouraged to show magnanimity. It signifies the collective prosperity of the community rather than individual achievements.[15] Sikpui Hla and the HlapuiThe songs accompanying the various Sikpui dances are collectively known as Sikpui Hla. The most sacred among these is the Sikpui Hlapui (Main Sikpui Song), which must be sung before the dances can commence.[15] One version of its lyrics translates as:

This song has generated considerable discussion due to its striking resemblance to the Exodus narrative of the Israelites, including references to a divided sea (possibly the Red Sea), guidance by a cloud and pillar of fire, and miraculous provision of quail and water from a rock.[15] This has led to various interpretations:

Regardless of its ultimate origin, the Sikpui Hlapui is a significant cultural artifact, preserving collective memories and narratives. Social cohesion and conflict resolutionFeasting plays a crucial role in Hmar society for fostering unity and resolving conflicts. The Sikpui Ruoi, with its communal feasting, serves this purpose. It was traditionally considered taboo to participate in the feast with grudges. Any enmity had to be resolved before the festival, promoting harmony.[15] The act of Tleng hmunkhata bufak (eating off the same plate) symbolizes oneness and peace.[15] An essential part of conflict resolution is the Inremna ruoi (Feast of Reconciliation), and the Sikpui Ruoi often facilitates such processes.[15] The communal dances, where men and women hold hands, also signify mutual acceptance and joy.[15] Other traditional songs and oral traditionsBesides the Sikpui Hla, the Hmar community has a rich repertoire of other traditional songs and oral literature that reflect their history, beliefs, and social customs. These are integral to ceremonies, other festivals, and communal gatherings, serving to preserve the language and cultural heritage. Notable examples include:

These songs, along with others, function as vessels of history, culture, and identity for the Hmar people. Efforts to document and preserve these songs contribute to maintaining the linguistic and cultural heritage of the Hmar language. See AlsoReferences

Status references

Traditional songs references

External Links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||