Submerged munitions

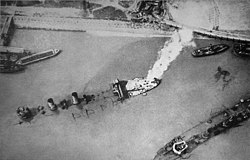

The term submerged munitions refers to situations where munitions have been lost or deliberately dumped into marine, freshwater, or brackish waters, sometimes continental or underground. These are generally effects of war or military activities. Regarding the issues, there is a dual risk: sometimes of explosion and, in all cases, in the long term, of pollution caused by munitions as well as chemical contamination of food chains (in the short or medium term). More than a century after the 1918 armistice, and over seventy years after the defeat of Nazi Germany, hundreds of thousands of tons of these submerged weapons (conventional or chemical) still rest in lakes or on the seabed and remain dangerous. In the event of leaks due to corrosion, they can poison or contaminate animals (fish, shellfish, crustaceans) consumed by humans or farm animals (in the form of fishmeal and oils). Given the high costs of addressing the problem and the lack of consensus on solutions.[1] and risk measurement, its consideration seems to have been postponed until the 2000s. Nature and origin of submerged munitions    These can be chemical or conventional munitions. Often, they were deliberately submerged to dispose of them at lower cost, to prevent them from falling into enemy hands, or because they risked exploding or leaking due to their degraded state. Another portion, which is not the most significant, was simply accidentally lost at sea following battles, shipwrecks, scuttlings, or beachings. Some areas distributed somewhat everywhere in the world were reserved for dropping heavy munitions (bombs, torpedoes, land mines) not used during aborted missions due to weather or counter-orders. It was too dangerous for aircraft to land with their munitions, or these would have excessively increased their fuel consumption, preventing them from returning safely. These munitions were therefore dropped into the sea before returning to base, sometimes quite close to the coasts. These jettison zones are theoretically prohibited for navigation (air or sea). They mainly date from World War II, which inaugurated the method of massive aerial bombings. In the OSPAR or Channel/North Sea zone, there are at least three: near the English coast, in the Thames estuary, and another in the Strait of Dover. For example, approximately 100,000 incendiary projectiles and nearly two hundred "Cookies" were reportedly dropped by a fleet of 138 Lancaster bombers of the RAF on December 15, 1944, in the Channel, following the attack on Siegen (east of Cologne), aborted due to fog.[2] A significant portion of these munitions did not explode and likely still rest on the bottom, at −35 m in this "Southern Jettison Area" ("jettison" in English refers to the act of throwing an object or waste overboard from a boat, submarine, plane, or helicopter; it can also refer to an aircraft dumping unconsumed fuel before a safe or emergency landing. In this case, predetermined jettison zones (called FJA "Fuel Jettison Area" by English speakers). The "Southern Jettison Area" lies under the current ascending lane of Channel maritime traffic, according to Michel Dehon.[3] Its center is at 50°15 N and 0°15 E, with a radius of 9 km. These three RAF aerial jettison zones were not taken into account in the inventory made for OSPAR, notes Michel Dehon.[3] Some marine and lake sites have been regularly used as target practice areas or for testing, including the special case of nuclear tests. Many unexploded ordnance have thus been lost during military tests or exercises and, in the case of misfires, not all have been recovered. Some countries (maritime or not, such as Switzerland) have used lakes and wetlands as exercise and dumping sites for obsolete munitions. In water (lake, sea, or closed wetland ...), even conventional munitions that exploded on impact can be a source of pollution by lead, mercury, or other metals. Submerged explosivesThe mention "Explosives submerged" on some nautical charts refers to underwater dump sites established since the end of World War I, but many deposits seem not to have been indicated on these charts. Since then, some deposits have also been partially dispersed by currents, tsunamis, and fishing trawls. These particular "objects" seem legally assimilable to "toxic or hazardous waste" likely to release into the environment many pollutants, including eutrophying agents and some very toxic products, in dispersed quantities (DTQD), most often and initially in low doses, but chronically. The risks of explosion or sudden and significant leakage are still poorly assessed and could vary depending on depth, salinity, currents, oxygen levels, and water temperature. The consequences encompass the domains of economy, environment, public health, civil protection, military affairs, and foresight. The impacts feared by experts in demining and ecotoxicology are mainly medium and long term and concern the entire food pyramid. FreshwaterFew data are published, but ancient munitions have been massively found, for example, in Lac de Gérardmer in France or in the Jardel sinkhole (120 m vertically) from which the springs of the Loue flow, in the Doubs. In Switzerland, one lake in two has reportedly received them, including large lakes such as Lake Thun, Lake Brienz, and Lake Lucerne. Risks and dangers Risks of direct contactA first, direct risk is that of death or injury following the spontaneous or accidentally triggered explosion of a munition. Thus, recently in 2005, 3 fishermen were killed in the southern part of the North Sea by the explosion, on their fishing boat, of a World War II bomb caught in their nets.[5] According to the OSPAR Commission, "The pressure exerted by the loud noise produced by spontaneous or controlled munition explosions can injure or kill certain marine mammals and fish. It has been reported that porpoises have been killed within a 4 km radius of explosions and others have suffered permanent hearing damage within a 30 km radius".[5] A second risk is that of exposure to mustard gas, the war toxicant that has been most massively dumped at sea. According to Andrulewicz (1996),[6] cases of capturing mustard gas in the form of viscous lumps or contamination of nets during bottom trawling have been recorded, particularly in the western part of the Polish coast, which is consistent with available data on dump sites and sea dumping routes. Some cases have been reported by the press:

Toxic leaksIt takes about 80 years for a munition to start leaking. The corrosion of munitions is a source of delayed toxic leaks in time and space, still poorly assessed, first because the situation is somewhat "new" in environmental history, but also because in Europe, secrecy has long surrounded marine munitions dumps; it was not until 2005 that the English public learned that the Beaufort's Dyke contained more than a million tons of munitions submerged there over more than 40 years. Concerning France, which seems to be one of the countries most affected in the world by munitions immersions, it was only in 2005 that a first official map, imprecise and without quantitative data, was published (with a five-year delay since these maps were to be published before 2000, in application of the London Convention and in accordance with the commitments of the member countries of the OSPAR Commission). The authorities responsible for these immersions seem to have long thought that there would be degradation followed by dilution of chemical toxins. However, at least in cold waters, most of the toxins from munitions have remained perfectly active after 80 years, some are neither degradable nor biodegradable (mercury, for example), and they can be quickly reconcentrated by filter-feeding organisms and the food chain. Several types of indirect risks must be taken into account, sometimes adding their effects in the form of contaminations of the ecosystem and/or marine materials (gravel pits, sand extraction) likely to be used.

An environmental assessment and concerning maritime safety is in Germany followed by the Ministry of Agriculture, Environment, and Rural Areas of Schleswig-Holstein[22] where, for reconstruction needs, significant quantities of munitions had already been recovered (in the 1950s and 1960s[22]). A study in 1996 focused on products released in this region or in the Baltic Sea by the spontaneous or induced underwater explosion of explosives or submerged munitions.[23] Two explosions of naval mines placed on the bottom were studied: the first placed at −15 m contained 100 kg of explosive (trinitrotoluene) and the other placed at −17 m contained 500 kg (TNT + RDX + aluminum). The water was sampled immediately after the explosion, in the water clouded by it up to 20 m and beyond this zone, with double sampling at three depths (at the surface, at 7.5 meters, and at 15 meters depth). In this case, the analysis (high-performance liquid chromatography) focused on the parameters TNT, (cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine or RDX), compounds of dinitrotoluene (2-amino-4,6-dinitrotoluene and 4-amino-2,6-dinitrotoluene). Tests following the DIN 32645 standard gave the following precision values:

In this case (TNT explosion), none of the molecules sought were found in the water samples taken, suggesting that TNT-based explosives decompose almost completely during the explosion. When there is no explosion but slow degradation underwater, it is unknown what processes are at work. It is known that TNT (which is almost insoluble in water) can nevertheless contaminate sediments (in 2007, up to 7.1 mg of trinitrotoluene (TNT) per kg of sediment was measured in this area, although TNT levels are usually undetectable). But there are no standards or consensus on a threshold not to be exceeded in seawater or sediments.[22] (As an indication, the German standard for soil of children's playgrounds requires not to exceed 20 mg/kg of soil[22]). In 2007, other water samples were taken one meter below the surface and one meter above the bottom and entrusted to independent laboratories in munitions immersion areas in the regions of Kolberg, Heide, and the Kiel Fjord; they did not contain solubilized explosive molecules above the detection limit.[22] Similarly, levels in sediments were often below the detection threshold (0.02 mg/kg). In one sample, TNT reached 7.1 mg/kg of sediment.[22] FranceIn France thousands of tons of munitions were recovered after World War 1914–18. Some were dismantled, others were brought to ports from the eleven departments of the "Red Zone" or from arsenals located further south, to be dumped at sea, despite a major risk of local and global pollution of marine and coastal ecosystems. Some lakes are also affected. It also seems that wells, old mines and galleries, old wetlands, or sinkholes (e.g., Jardel sinkhole) are locally concerned. Overseas, many World War II munitions still rest, including mines, for example in the Nouméa lagoon where nearly 1,600 Mk. XIV mines (from World War II) are still present in the lagoon.[24] Trawlers often bring up shells or other types of munitions, sometimes requiring the intervention of deminers (91 contacts were declared in 2004[25]). They sometimes bring up rare objects; thus, 3 shells of 280 mm, 50 cm long, and weighing about 100 kg were brought up on November 30, 2007, by the Breton trawler l'Alcatraz from Lorient, 11 km from Groix island, which justified the displacement of 4 diver-deminers.[26] The latter re-submerged these shells to destroy them underwater 2.5 kilometers east of the Gâvres point where there is a test center of the General Delegation for Armament (former Ballistics, Weapons, and Munitions Research and Study Group (GERBAM)). This type of munition, unusual, was only used by small German "pocket battleships" (Deutschland, Sheer, and Admiral Graf Spee) and the battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau which stayed in Brest from March 22, 1941, to February 11, 1942, before returning to Germany via the Strait of Dover (Operation Cerberus). In France, the neutralization of submerged explosive devices on the maritime domain (up to the high tide mark) is the responsibility of the Navy. Thus, each year since the end of World War II, diver-deminers neutralize nearly 2,000 devices found at sea by fishermen or on beaches by walkers. The Agence des aires marines protégées and the NGO Robin des Bois alerted the Grenelle de la mer in 2009 and proposed that inventories of underwater dumps of chemical munitions and nuclear waste be completed, with an assessment of possible impacts on sedentary fauna and flora and sediments. This proposal was accepted.[25] United KingdomMunitions were probably submerged as early as 1920 in Beaufort's Dyke, and about one million tons were submerged there after World War II, including munitions containing phosphorus. Under the authority of Douglas Haig, the United Kingdom (with the United States) also supervised the destruction or elimination of unexploded munitions collected in northern France at the time of reconstruction after the Armistice of 1918, while Andrew Weir (1st Baron Inverforth) was Minister of Munitions in Great Britain. NorwayAccording to Doyle in 2004, in areas appreciated by fishermen, Norway was still trying to locate or assess the state of 15 or even 36 wrecks of ships sunk at sea after being loaded with more than 168,000 tons of German army munitions[27] ProblemsUsed, stored, or lost, munitions (including chemical shells) or their contents constitute a lasting threat[28].

ResponsibilitiesIt seems accepted that in the case of the legacies of world wars, once negotiations on war damage are closed and peace agreements signed, the search for responsibility is no longer to be done, and it is then up to the States to subsidiarily manage the issue of legacies on their territories (which does not exclude subsequent cooperation agreements). Reflection has been underway on a European and global scale for a few years but has not led to a global cooperation program or common financing. An international convention commits its signatory countries to produce an inventory for the year 2000 and to have destroyed their stocks (of chemical weapons) by 2007. Few countries are up to date with their commitments. Speed of degradation of munition casingsLeaks occur after a very variable delay depending on the initial state of the munition, and depending on the conditions of the environment (the danger will then be linked to the level of toxicity, and bioavailability of the compounds of the munition, and their quantity. In cold water, nitrate cords degrade only slowly. In a stable environment (in the absence of current and passage of fishing trawl and in an undisturbed, non-bioturbated mud), the mustard gas lost by a corroded shell submerged after World War II remains "within a 3 cm radius around the shell".[5] It is different if this shell is moved or brought up in a trawl or by the current. It is generally estimated that shells submerged from World War I must have started to leak after about 80 years, but theoretical models do not always prove reliable (perhaps due to the acidity of certain components, such as picric acid). Thus, in Hawaii, munitions have corroded faster than expected according to an American study (published in 2009). Researchers used ROVs and manned vehicles to assess in situ the integrity or state of degradation of military munitions (conventional and chemical) sunk by the Department of Defense off Hawaii (over 69 km²) south of Pearl Harbor. 1,842 non-chemical munitions were inspected on this occasion: only 5% were slightly modified, and most (66%) were heavily corroded although apparently intact; 29% were already heavily corroded and breached (contents exposed).[30] In addition, "unusual" forms of corrosion were reported (flows that seem to have been subsequently cemented with sediment, probably due to chemical or biochemical reactions involving microbes, which could not be proven as there were no samples taken during this study); a "trapping of certain corrosion products" seems to occur in these cases.[30] Chemical weapons are supposed to be generally stronger and made with thicker casings; they should therefore leak later.[30] In the Baltic, where many dumps (of mustard gas[31] in particular) were made, fishermen are already frequently burned by mustard gas brought up in their nets, and one can wonder if contaminated fish have not already been marketed. But, except for an accident or terrorist act, the potential major problems are mainly medium and long term. Because if the deliberate immersion at sea or in lakes of military waste and unexploded ordnance began massively in the years 1919–1920, with a second wave after 1945, it is around the years 2000/2005 that the shells, naval mines, torpedoes, etc. submerged at sea should – due to their corrosion – begin to leak. Those that were submerged in freshwater or in soft, oxygen-poor sediments should leak much later. Indeed, the cast iron steel that constitutes the casing of shells is on average 5 to 6 millimeters thick; it corrodes at an average rate of 0.1 to 0.5 mm/year. Moreover, picric acid, the most common explosive in 1914–1918 shells, can accelerate this corrosion and give rise to "picrates", likely to explode at the slightest shock. In addition, since shells are often stacked in thick piles, and sometimes with other types of munitions (grenades, torpedoes, mines, cartridges, etc.), the weight of those on top can crush those that have prematurely weakened below, causing sudden and significant leaks of toxins and/or eutrophying agents. The impacts of water pressure are poorly known. Some combat toxins were protected by lead packaging or in a hermetically sealed glass bottle (e.g., arsines), whose behavior at great depth is unknown. Quantities A first problem is that, depending on the countries and periods, the tonnages cited may concern the weight of toxins or the weight of toxins and their containers. Theoretically, since 1993, we should now clearly differentiate these two notions;[32] in 1993, the meeting of the parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) requested that reference be made only to the weight of chemical agents, unless expressly mentioned that it also includes the total weight of munitions or other containers (munitions and devices).[33] Among the countries or regions that have quickly acknowledged having submerged chemical weapons are at least: Ireland, Great Britain, Scotland (Beaufort's Dyke), the Isle of Man, Australia (with notably, according to a 2003 government report, more than 21,000 tons of chemical weapons submerged off the coasts at the end of the 1940s[34][35][36]), Russia, the United States, Japan, Canada. Belgium, in the 1980s, became aware again of the famous Zeebrugge deposit (35,000 tons), and France remained very discreet about its immersion activities but, although archives are scarce, historians had traces or indications of immersion of old munition stocks in the Mediterranean and the Bay of Biscay as well as in the Casquets Trench located between Brittany and the United Kingdom. The nautical charts of the SHOM also include some marks "explosives submerged" on the Atlantic coast and that of the Channel/North Sea.[37] Controversies exist. For example, according to a documentary broadcast (2010/01/03) by the Swedish channel SVT, dangerous military waste (including perhaps radioactive waste[38]) was evacuated from a former Soviet military base in Latvia and dumped at sea by Soviet ships, at night, near the island of Gotland (Sweden's economic zone), between 1989 and 1992. ; Vil Mirzayanov (former Russian military chemist who once worked in a secret weapons laboratory, arrested for writing articles on new chemical agents, then released) believes that immersions were a common practice at that time; to get rid of toxic materials or to hide illegal chemical weapons. Swedish politicians have called for an official investigation as a pipeline is to pass through this area.[39] A trench near the island received a large quantity of munitions, which are starting to leak.[40] Millions of tons of submerged munitions are often forgottenAccording to French demining specialists, questioned by a commission on demining (chaired by Jacques Larché, senator), a quarter of the billion shells fired during World War I and a tenth of the shells fired during World War II did not explode during these conflicts. Moreover, it is known, from finding them, that large shells from World War I penetrated at least 15 m deep into relatively hard soils without exploding. It is feared that in marshes, peat bogs, mudflats, forest ponds, rivers, and canals, shells have penetrated much deeper. It is known that when falling on soft sediments, up to eight out of ten shells did not explode. Finally, according to some experts, about half of the munitions and incendiary materials used during the two world wars did not function on impact.

These problems have, in France, motivated a resolution proposal (No. 331, 2000–2001), aimed at creating an inquiry commission on the presence on national territory of munition deposits from the two world wars, the storage conditions of these munitions, and their destruction (presented by MM. Jacques Machet, Philippe Arnaud, Jacques Baudot, and Rémi Herment, senators), and there is a study group on civil security and defense in the Senate. According to available data and recently provided by the respective States to the European Union and the OSPAR Commission or HELCOM, etc. Since the 1920s, more than 1 million tons of munitions (mainly conventional) have been deliberately sunk just in Beaufort's Dyke, 200 to 300 m (656 to 984 feet) deep between Scotland and Northern Ireland. A 1996 study showed no contamination of fish, but nothing guarantees the long-term harmlessness of this solution or that the fauna will not concentrate the toxins thus stored. In this region, Scottish and Irish fishermen are, by derogation, authorized to throw back into the sea munitions brought up in their nets, although the law invites them to bring them back for elimination on land when it can be done safely.[41] Just in the Baltic, and after World War II, it would be 30,000 to 40,000 tons of chemical weapons that were submerged.[42] At sea, dozens of major sites for immersion of waste and munitions and hundreds (thousands?) of other smaller sites exist. Many of them seem to have been forgotten or recently rediscovered by local and national elected officials. Several tens of thousands of tons (including chemical shells) are stored in each of the largest of these sites. They can sometimes be located at shallow depths (Frisian Islands) and a few cables from a coast or an industrial port (for example, for the Paardenmarkt bank where tens of thousands of tons of old munitions rest in Zeebrugge in Belgium,[43] where a recent administrative report concluded that it was better for now not to touch this deposit[44]),[45][46] and where a pentagon[47] is prohibited for fishing and any anchoring,[48][49] but partly in an SPA (special protection area for birds) and close to fishing areas or spawning grounds or marine currents irrigating areas of essential biological productivity... Some ships during battles sank with their toxic cargo without being located. There does not seem to be a map listing these risks and dangers. Management by countryUnder the auspices of the UN or other bodies, the immersion of munitions was banned in the last quarter of the 20th century by the laws of countries that ratified certain agreements and conventions.[50] Operations for sharing information and environmental assessment are underway, including under the aegis of conventions (OSPAR, HELCOM, European directives, or resolutions of networks of communities (e.g., KIMO).[51] NATOOn April 27, 1995, a NATO study on "Cross-border environmental problems caused by defense-related facilities or activities" was presented at the annual meeting of the CCMS (Committee on the Challenges of Modern Society) of NATO, opened for the first time to observers from PfP countries (Austria, Finland, Slovenia, and Sweden).[52] Regarding radioactive and chemical contamination of the environment, this study notably concludes that:[52]

The Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation (CMRE) has set up an underwater laboratory and test site at the SACLANT Undersea Research Centre (SACLANTCEN, SACLANT being the acronym for Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic) in La Spezia, Italy, allowing work on submerged unexploded munitions. This military research center, led by Stefano Biagini (2019), offers its users the possibility to compare various robotic systems and algorithms on site, to test, in a known environment, robotic interventions intended to protect divers in potentially dangerous or contaminated environments, among other things.[53][54] The CMRE considers itself one of the world leaders in oceanography, anti-mine countermeasures, underwater autonomy, acoustic signal processing, and automatic target recognition, and it had a site in La Spezia.[54] Experiments lasting several weeks can be conducted there, benefiting from CMRE's experience as well as services (engineering specialized, laboratory spaces, mechanical workshops, and deployment support). These services will be open to external participants and end-users, encouraging international collaboration. The CMRE claims to be impartial and "independent of NATO".[54] It says it wants to build a "transatlantic American-European UXO Hub" in La Spezia[54] and "establish itself as a provider of controlled experiments in the Mediterranean Sea".[54] It says (in 2021) that it is preparing a workshop on the first feedback from the use of the CMRE UXO test bench; then a conference on the detection, classification, and identification of UXO. But the CMRE announces that it will distribute the proceedings only within NATO and the military community.[54] United StatesThrough its SERDP (Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program), the Department of Defense (DoD) financially supports, in a more targeted manner, advanced technologies and research (fundamental and applied) that can improve the treatment of the problem of submerged unexploded military munitions (UXO).[55] The objective is to reduce costs, environmental risks, and the time required to address these war waste, via three paths:[55]

Within the Naval Research Laboratory, Dr. Shawn Mulvaney and his team have thus successfully tested a system of advanced, high-power geophysical-class electromagnetic induction (EMI) sensors, integrated into a towed platform (MTA) to map and classify UXO while remaining at safe distances, allowing for optimized recovery.[56] A resource center (Munitions Response Library or MRL, managed by Dr. Penko)[57] includes a repository of software, data, and models useful for managing sites contaminated by submerged munitions;[56] it should become an online portal, partly public.[57] In 2021, ESTCP funded several munitions response demonstration projects tested on test bench sites, and other funding is planned for the coming years through calls for tenders or project grants.[55] EuropeAlmost all Western European countries have signed the conventions prohibiting immersion, but they must manage the legacies of immersions prior to the convention, including munitions or forgotten deposits that reappear with port works, cable immersions, pipeline laying (including the one that is to cross the Baltic[58]), underwater gravel pits, wind turbine projects, or offshore drilling.[59] It also appears that, even in Europe and in geographically close areas, depending on salinity, metals, shell contents (picric acid...), and the nature of the muds that may cover the shells, their corrosion rate varies considerably. The "immersion can lead to undesirable situations, and governments are then no longer able to control the munitions", recalls the OSCE.[29] For munitions landfilled (below the water table, in contact with runoff water, or submerged in lakes), the OSCE adds:

Among the countries concerned are notably, around the Baltic, Sweden, which produced an assessment in 1998,[60] Denmark,[61] and Poland,[62] Northern Germany, with, for example, the immersion of chemical weapons about 5 miles off the coast of Lübeck.[58] In Western Europe, France is the country most affected, but Scotland[63] and the United Kingdom are not spared by this type of legacy, on land[64] or at sea.[65] GermanyIn the north of the country, a site is dedicated to this activity with two chemical shell dismantling and soil decontamination facilities. This is a former production and testing site that suffered at least two major accidents: in 1919, the explosion of a munitions train spread nearly a million shells in the surroundings. At the end of World War II, when the Americans and the British arrived at this site, they destroyed facilities without sufficient precautions, leaving serious pollution legacies. A fully automated installation was put into service in 1995 to treat soils polluted by arsenic derivatives and chemical munitions with difficulties that caused two years of delay and called into question certain technical principles. In 2023, Germany launches an immediate munition recovery program, aimed at recovering the 1.6 million tons of munitions and 5,000 tons of combat gas submerged off its coasts during and after the two wars. Preliminary studies had noted a high rate of cancers in the marine fauna of munition immersion areas. Recovery operations benefit from a context where investors wishing to install wind turbines at sea have an interest in demining; knowledge of deposits has progressed; and the appointment of Steffi Lemke to the Ministry of Ecology. The program has started, and it is currently in the learning phase in the easiest areas.[66] BelgiumIn 1993, the principle of mechanical dismantling was retained; it has been operational since October 1999, with two years of delay. The shells are transported by hand, but cutting and slicing are done remotely before technicians in diving suits empty the shell, recover the toxin, clean the explosive, and destroy it elsewhere. This "artisanal" process requires highly qualified personnel and allows the destruction of certain types of munitions, but it is very limited in capacity (10 to 20 munitions/day), a capacity just sufficient to destroy the flows discovered and not to absorb their terrestrial stocks of 250 tons of shells. Other installations would be under study to increase this capacity.[67] France Prefectural decreePrefectural decree No. 13/89 of the maritime prefect of the Channel and the North Sea (known as "arr. prémar 13–89") concerning the deposit of suspicious devices found at sea explains what fishermen who find munitions in their nets must do. In application of this decree, a "Guide for fishermen on the conduct to be observed in the event of discovery or recovery at sea of explosives, containers, or drums" was made in 1995, mentioning compensation for discoverers of devices under certain conditions. Nevertheless, it seems that fishermen, who are the greatest "discoverers" of suspicious devices, most often throw back into the sea the shells they pick up in their nets, sometimes on the nearest wreck and, generally in France, without notifying the CROSS. They can benefit from a mapping of wrecks made by the SHOM to reduce the risk of catching their nets on wrecks and spreading munitions lost by these wrecks (mapping available on CD Rom[69]). ImmersionMunition immersion practices ceased in 2000 according to the Navy, notably following an accident that killed five sailors and pyrotechnicians on April 30, 1997, off Cap Lévi, near Cherbourg, on the barge La Fidèle, during a transport of grenades that were about to be submerged.[70] It was the 6th campaign to destroy 1,400 expired grenades. Since then, this type of munitions is entrusted to specialized companies via a NATO agency which, for example, transferred 650 tons to a German company in 2005 (at a cost of 1,000 €/t[70]). Brought to knowledgeDue to lack of brought to knowledge, the PREDIS (Regional plans for the elimination of industrial and special waste) then the Plan national santé-environnement as well as the PRSE 2 have omitted to take into account these aspects which are usually directly managed by the State, like the nuclear risk. Coastal regions and their elected officials do not seem to have "brought to knowledge" on the nature, volume, age, or possible presence of submerged munition stocks near or not their coast. The inventories and "states of play" prior to the application of the Water Framework Directive did not integrate this issue either, nor did the databases on polluted or potentially polluted sites (BASIAS and BASOL), although they have an appropriate section. DestructionDecree No. 96-1081 of December 5, 1996, gave responsibility to the Ministry of Defense to destroy ancient chemical munitions (200 to 300 different types of munitions). This operation was entrusted within the ministry to the General Delegation for Armament and more particularly to the nuclear programs service. The destruction capacity was initially set at 100 t/year for France, with a lifespan of 30 years for the facility to be built. Estimated cost at the time: 880 million francs. This facility was planned to operate in 2 x 8 or 3 x 8, thus being able to increase the processing capacity to 200 t/year or 300 t/year. At the end of 2000, the capacity of this facility was set at approximately 25 t/year at cruising speed, which corresponds to the annual discovery flow. This capacity will be increased at the beginning of the process to 75 or even 80 t to allow the destruction of the existing terrestrial stock during the first years of operation.[67] Offshore wind turbinesA project of 156 offshore wind turbines in front of Criel and Cayeux-sur-Mer in Picardy called "Project of the Two Coasts, estimated at 1.4 billion euros, to be put into service in 2010 by the Compagnie du Vent was blocked[71] by the Maritime Prefecture of the Channel due to the presence of munitions (old minefields) on the site. This project was to require 2,000 people during the three years of construction, and 250 jobs for operation, with a tax of 8.5 million euros, paid half to local fishing committees to compensate them. The group proposes to ensure the demining of the site if the project is authorized. Similar problems have been posed in Great Britain, in the Baltic Sea during the construction of the bridge connecting Sweden to Denmark and concerning the gas pipeline project that is to cross the Baltic but without blocking these projects. DGAThe Direction générale de l'Armement (DGA) announced that, like in the northern countries, it would seek to better respect the environment with "green munitions", soil depollution, and a budget of 150 million euros to be spent before 2008 for the depollution of military land and as much for the research of "green" materials, less toxic and less noisy. However, it seems that the sites concerned are only those that belong to the army and only located on land and not under the sea. Grenelle de la merGrenelle de la mer: In mid-2009, one of the retained proposals (No. 94.d)[72] in the "commitments" of the Grenelle de la mer is to:

In its report[73] (April 2010), ComOp No. 13 marine pollutions specifies that its attention "was drawn to commitment 94.d" but that:[73]

DeminingPunctual demining missions exist: in 2008, a NATO mission destroyed about fifteen large World War II devices equivalent to 8 tons of TNT. From May 17 to 24, 2010, in the Channel, France called on NATO's mutualized means for underwater demining of an area located off the Pays de Caux (Seine-Maritime) and the Baie de Somme, site of the future Parc naturel marin des trois estuaires; 674 sailors from 9 countries[68] on ten minehunters will operate in two groups respectively coordinated by the command ships Kontradmiral Xawery Czernicki (Poland) and the Italian frigate Granatiere. They will work on "the cleanup of the seabed and the securing of maritime activities". According to the Cherbourg maritime prefecture, these are "mostly devices dating from World War II and most are German".[74] It would be the 5th operation of this type since 2007.[75] SwitzerlandIn Switzerland, where one lake in two has reportedly received them, at least 8,000 tons of shells, detonators, or bombs have been thrown into various lakes and, despite a motion from the lower house in 2005 (before the analyses),[76] the authorities decided to leave them there. After numerous analyses, nothing allows to affirm that these munitions have polluted the lakes. The majority of these munitions are covered by 25 cm to 2 m of mud, and their extraction would deeply disturb the lake bottoms and consequently the lake ecosystems.[77][78] Lake Thun contains 4,600 tons of munitions that were submerged between 1920 and 1963. Many fish, including more than 40% of whitefish (or palées), are victims of congenital and sexual anomalies without the analyses carried out being able to establish that they are induced by leaks of toxins from the thousands of munitions thrown at the bottom of the lake.[79] Lake Lucerne contains 2,800 tons deposited in the Uri lake, plus 530 tons in the Gersau basin. Lake Brienz contains 280 tons that were dumped there, part of which was cleaned up in 1991 by eliminating munitions close to the shore. The deposits of these three lakes represent 95% of the submerged stocks in Switzerland.[80][81] In various other lakes (Lake Walen, Lac d'Alpnach in Lake Lucerne, Lake Greifen, lakes at the Gotthard Pass, Lake Lauerz), ancient dumps of various military materials have been confirmed by the DDPS in 2004. According to recent data, 8,200 tons of munitions were thrown into Lakes Thun, Brienz, and Lucerne alone. And other waste such as military surplus, cooking oils, or gas masks were also thrown there[82] PerspectivesOfficial programsDespite some alerts from associations or personalities, following accidents or fortuitous discoveries, or information that remained almost confidential, the ecotoxicological and health aspect of war legacies, when not simply denied, has curiously been eluded by historians of the period. While the centenary of the 1914–18 war is being prepared, France, despite repeated injunctions from the OSPAR Commission, despite alerts from NATO (in 1995–1996), and despite pressing recommendations from the HELCOM Commission and then the European Commission, declared its underwater immersion sites – with 5 years of delay and imprecisely – only in 2005, pushed by its international obligations. Official programs target only the dismantling of chemical weapons stored on national soil or found by deminers. France, although being the country most affected by war legacies for the period 1914–1918, evoked this problem only after Germany, Belgium, the United Kingdom, the Baltic countries, and more discreetly than them. History will perhaps tell if this is explained by the weight of military secrecy or by a will to forget specific to the 1920s in France where – for the post-14-18 period – the horrors of this war were difficult to say, not to say, and to "forget", particularly about combat gases. These gases traumatized public opinion to the point that none of the belligerents in Europe or North America accepted to use them during World War II, preferring the atomic weapon, while they had accumulated considerable stocks of chemical weapons; these stocks were also partly thrown into the sea. Risk of corrosion and contaminationAs time passes, buried and submerged munitions corrode, and the risk of serious contamination increases. And to the forgotten munitions of the first, but also of the Second World War (including chemical weapons[83]), are added those that were manufactured and stored during the second half of the 20th century, which most countries have committed to destroy before 2007, an objective that does not seem achievable given the means that countries have given themselves. Finally, there are probably indirect impacts on the sea (and in freshwater). In southern France, in Germany, in Belgium, chemical shells were demilitarized after the war without officially measuring the residual impacts. Munitions were submerged in freshwater (7,000 tons of munitions coming 90% from the period 1914–1918, including 4 million hand grenades thrown into the Avrillé lake, the Jardel sinkhole), and relic pollutions may exist in unexpected places. The sea being the natural receptacle of watersheds and certain aquifers, it also receives pollutants carried by runoff or certain underground aquifers, some of which may come from unexploded munitions degrading. OSPAROSPAR has prepared a "Framework for the development of national guidelines" to be used in the event of contact with munitions by fishermen or coastal users. Cleaning up immersion sites has long been considered even riskier than letting munitions disintegrate over time, but in any case, serious risks exist for the environment and health.[5] According to OSPAR, "if there is a need to remove munitions from the seabed, consideration should be given to using new techniques that allow them to be neutralized without exploding them". Traditionally, deminers destroy dangerous munitions by exploding them, but this method then spreads the toxins they contained into the environment. OSPAR wishes to "encourage the development of techniques to safely remove or neutralize munitions without explosion and promote monitoring of the potential effects of submerged munitions in the North-East Atlantic".[5] It would also be necessary to "avoid explosions because the underwater noise and the release of hazardous substances they cause are of concern". OSPAR recommended in 2010 the publication of "national guidelines" for fishermen and coastal users in case of contact with munitions, as well as the distribution to fishermen of "subsurface marking buoys to be used in case of discovery"[5] European mutualizationIn Europe, the Belgian Minister of Defense proposed the principle of creating a "European agency for the destruction of chemical and conventional munitions". This principle was decided with a first preparatory meeting held in Brussels on May 4, 2001. However, a European munitions destruction plant raises the problem of its financing (high costs) and the risks related to the transport of these very dangerous objects. In Germany, some Länder oppose the transport of these munitions on their territory. The Marine Strategy Framework Directive, which might have to be applied in 2008, specifies (in its Annex II) that the problem of submerged munitions must be assessed and addressed, but it leaves great freedom to States on the choice of means and provides for special cases that could perhaps concern this problem. The European Union has produced a "community framework for cooperation between Member States in the field of accidental or intentional marine pollution"[84] allowing[85] to finance 100% of the "Actions promoting the exchange of information between competent authorities" on the risks related to the immersion of munitions; the areas concerned (including the establishment of maps); the taking of emergency intervention measures. See alsoReferences

Bibliography

External links

|