South Nahanni River

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Artikel ini bukan mengenai wafel. WaferWafer berwarna merah jambuSunting kotak info • L • BBantuan penggunaan templat ini Media: Wafer Wafer adalah sejenis biskuit yang renyah, memiliki rasa yang manis, dengan bentuk tipis, datar, dan kering,[1] sering dipakai sebagai tambahan untuk es krim. Wafer juga dapat diolah menjadi kue kering dengan lapisan krim. Wafer sering kali memiliki pola permukaan seperti wafel, tetapi juga dapat bermotif lambang produsen makanan...

Mato Jajalo Informasi pribadiTanggal lahir 25 Mei 1988 (umur 35)Tempat lahir Jajce, SFR YugoslaviaTinggi 1,81 m (5 ft 11+1⁄2 in)Posisi bermain GelandangInformasi klubKlub saat ini PalermoNomor 28Karier junior1993–1999 DJK Eiche Offenbach1999–2007 Slaven BelupoKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2007–2009 Slaven Belupo 63 (8)2009–2010 Siena 25 (0)2010–2014 1. FC Köln 90 (5)2014 → Sarajevo (pinjaman) 9 (0)2014–2015 Rijeka 18 (1)2015– Palermo 3 (0)Tim ...

لا إطار كأس العالم للأندية لكرة القدم وعرفت سابقاً باسم بطولة العالم للأندية في نسختي 2000 و2005، هي بطولة كرة قدم دولية أحدثها الاتحاد الدولي لكرة القدم لتعوض مسابقة كأس الإنتركونتيننتال. أعلنت الفيفا عام 1999 عن إنشاء بطولة جديدة يشارك فيها كل أبطال الاتحادات القارية لإضفاء ن...

Video rumahan adalah perangkat video yang berupa VHS, VCD, DVD, maupun media sejenis lainnya secara hukum internasional dilarang dipertontonkan secara umum, apalagi digunakan untuk keperluan finansial. Pada awalnya, istilah ini populer pada era VHS/Betamax. Seiring perkembangan teknologi dan berkembangnya format yang lainnya seperti DVD dan Blu-ray Disc, istilah ini masih digunakan. Sebuah DVD Video rumahan biasanya diperjualbelikan dan disewakan untuk ditonton untuk kebutuhan pribadi. Di neg...

NOAA weather satellite GOES-2Artist's impression of an SMS-series GOES satellite in orbitMission typeWeather satelliteOperatorNOAA / NASACOSPAR ID1977-048A SATCAT no.10061Mission duration24 years Spacecraft propertiesSpacecraft typeSMSManufacturerFord AerospaceLaunch mass295 kilograms (650 lb) Start of missionLaunch date16 June 1977, 10:51:00 (1977-06-16UTC10:51Z) UTCRocketDelta 2914Launch siteCape Canaveral LC-17BContractorMcDonnell Douglas End of missionDisposalDecommissioned...

Chronologies La place des Pyramides - Giuseppe De Nittis, 1875. Le bâtiment couvert d’échafaudages est le pavillon de Marsan (incendié pendant la Commune), alors en cours de reconstruction.Données clés 1872 1873 1874 1875 1876 1877 1878Décennies :1840 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900Siècles :XVIIe XVIIIe XIXe XXe XXIeMillénaires :-Ier Ier IIe IIIe Chronologies géographiques Afrique Afrique du Sud, Algérie, Angola, Bénin...

American actor (1908–1969) For the California politician, see Bud Collier. This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Bud Collyer – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Bud CollyerCollyer in 1962BornClayton Johnson Heermance, J...

Salvador Cabañas Cabañas pada tahun 2016Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Salvador Cabañas OrtegaTanggal lahir 5 Agustus 1980 (umur 43)Tempat lahir Asunción, ParaguayTinggi 173 m (567 ft 7 in)Posisi bermain Penyerang, sayapKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)1998–2001 12 de Octubre 28 (14)1999 → Guaraní (pinjaman) 20 (6)2001–2003 Audax Italiano 53 (29)2003–2006 Chiapas 103 (59)2006–2010 América 115 (96)2012 12 de Octubre 14 (0)Total 337 (174)Tim nasional‡199...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant l’Écosse. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. CaithnessNoms locaux (gd) Gallaibh, (ga) CataibhGéographiePays Royaume-UniNation constitutive ÉcosseSubdivision HighlandÎle Grande-BretagneChef-lieu WickSuperficie 1 600,61 km2Coordonnées 58° 25′ 00″ N, 3° 30′ 00″ ODémographiePopulation 26 486...

Шалфей обыкновенный Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:РастенияКлада:Цветковые растенияКлада:ЭвдикотыКлада:СуперастеридыКлада:АстеридыКлада:ЛамиидыПорядок:ЯсноткоцветныеСемейство:ЯснотковыеРод:ШалфейВид:Шалфей обыкновенный Международное научное наз...

Austrian philosopher of science (1924–1994) Paul FeyerabendFeyerabend at BerkeleyBorn(1924-01-13)January 13, 1924Vienna, AustriaDiedFebruary 11, 1994(1994-02-11) (aged 70)Genolier, Vaud, SwitzerlandEducationUniversity of Vienna (PhD, 1951)Era20th-century philosophyRegionWestern philosophySchoolAnalytic philosophy[1]InstitutionsUniversity of California, BerkeleyETH ZurichThesisZur Theorie der Basissätze (A Theory of Basic Statements) (1951)Doctoral advisorVictor KraftOther...

UNESCO World Heritage Site in Tamil Nadu, India Great Living Chola TemplesUNESCO World Heritage SiteScenes from the three templesLocationTamil Nadu, IndiaIncludesThe Brihadisvara Temple Complex, ThanjavurThe Brihadisvara Temple Complex, GangaikondacholapuramThe Airavatesvara Temple Complex, KumbakonamCriteriaCultural: (ii), (iii)Reference250bisInscription1986 (10th Session)Extensions2004Area21.88 ha (54.1 acres)Buffer zone16.715 ha (41.30 acres)Coordinates10°46′59″N ...

Armed border guard of the Soviet Union This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Soviet Border Troops – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Soviet Border TroopsПограничные войска СССРPograníchnyye Voiská SSSRPatch...

Component which maintains a setpoint temperature This article is about the temperature regulating device. For the French cooking oven temperature scale, see Gas Mark § Other cooking temperature scales. This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Thermostat – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JS...

Andraž Kirm Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Andraž KirmTanggal lahir 6 September 1984 (umur 39)Tempat lahir Ljubljana, SFR YugoslaviaTinggi 183 m (600 ft 5 in)[1]Posisi bermain Midfielder / WingerInformasi klubKlub saat ini GroningenNomor 17Karier junior1991–2002 ŠmartnoKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2002–2003 Slovan 17 (1)2004–2005 Svoboda 38 (4)2005–2009 Domžale 127 (22)2009–2012 Wisła Kraków 83 (16)2012– Groningen 10 (0)Tim nasional‡2007�...

Swiss event construction company NussliCompany typePrivateIndustryEvent and Exhibition Construction, Temporary Structures, Stadium ConstructionFounded1941 in Hüttwilen, SwitzerlandFounderHeini NüssliHeadquartersHüttwilen, SwitzerlandArea servedWorldwideKey peopleAndy Böckli (CEO)[1]ProductsEvent construction: Grandstands · Bleachers · Seating · Stages · Stadium Construction // Trade Fair Stand Construction · Pa...

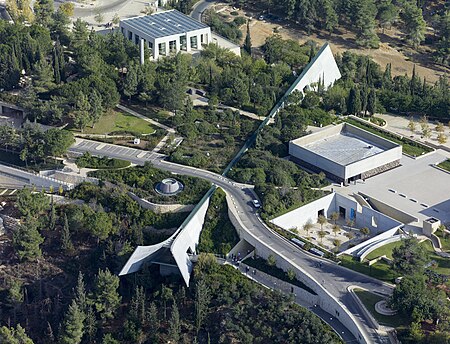

Israel's official memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust Yad Vashemיָד וַשֵׁםAerial view of Yad VashemEstablished19 August 1953LocationOn the western slope of Mount Herzl, also known as the Mount of Remembrance, a height in western Jerusalem, IsraelCoordinates31°46′27″N 35°10′32″E / 31.77417°N 35.17556°E / 31.77417; 35.17556TypeIsrael's official memorial to the victims of the HolocaustVisitorsabout 925,000 (2017),[1] 800,000...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento centri abitati del Piemonte non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Tortonacomune Tortona – VedutaFacciata superiore del duomo LocalizzazioneStato Italia Regione Piemonte Provincia Alessandria AmministrazioneSindacoFederico Chiodi (Lega) dal 27-5-2019 TerritorioCoordinate44°53′39�...

Meri Kuri or Merry-ChriSingel oleh BoAdari album Best of SoulDirilis Jepang dan Korea Selatan:1 Desember 2004FormatCDDirekam?GenrePopDurasi Labelavex traxProduser? Meri Kuri atau Merry-Chri adalah album solo Jepang ke-14 BoA dan album solo Korea ke-3 BoA. Dua versi singel ini dirilis di Jepang dan Korea. Lagu Versi Jepang メリクリ (Meri Kuri) MEGA STEP THE CHRISTMAS SONG メリクリ (Instrumental) (Meri Kuri - Instrumental -) MEGA STEP (Instrumental) Versi Korea 메리-크리 (...

Region of Virginia 37°36′10″N 76°39′15″W / 37.60278°N 76.65417°W / 37.60278; -76.65417 Map of Virginia with the Middle Peninsula in red. The Middle Peninsula is the second of three large peninsulas on the western shore of Chesapeake Bay in Virginia. To the north the Rappahannock River separates it from the Northern Neck peninsula. To the south the York River separates it from the Virginia Peninsula.[1] [2] It encompasses six Virginia countie...