Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit, BWV 106

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Rumah Sakit MersingHospital MersingGeografiLokasiMersing, Johor, MalaysiaKoordinat2°25′44.0″N 103°50′44.4″E / 2.428889°N 103.845667°E / 2.428889; 103.845667Koordinat: 2°25′44.0″N 103°50′44.4″E / 2.428889°N 103.845667°E / 2.428889; 103.845667OrganisasiJenisrumah sakit Rumah Sakit Mersing (Melayu: Hospital Mersingcode: ms is deprecated ) adalah sebuah rumah sakit di Mersing, Johor, Malaysia. Sejarah Rumah Sakit Mersing didi...

Film Indonesiaberdasarkan tahun 1920-an 1926 1927 1928 1929 1930-an 1930 1931 1932 1933 1934 1935 1936 1937 1938 1939 1940-an 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1948 1949 1950-an 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960-an 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970-an 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980-an 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990-an 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000-an 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 200...

Village in Estonia Village in Harju County, EstoniaMeremõisaVillageCountry EstoniaCountyHarju CountyParishLääne-Harju ParishPopulation (31 December 2021[1]) • Total163Time zoneUTC+2 (EET) • Summer (DST)UTC+3 (EEST) Meremõisa is a village in Lääne-Harju Parish, Harju County in northern Estonia.[2] Meremõisa is about 27 km (17 mi) west of the capital Tallinn, west of Keila-Joa, and next to Lohusalu Bay, which is part of the Gulf...

Vermont gubernatorial election 1837 Vermont gubernatorial election ← 1836 September 5, 1837 1838 → Nominee Silas H. Jennison William Czar Bradley Party Whig Democratic Popular vote 22,260 17,730 Percentage 55.65% 44.33% Governor before election Silas H. Jennison Whig Elected Governor Silas H. Jennison Whig Elections in Vermont Federal government Presidential elections 1792 1796 1800 1804 1808 1812 1816 1820 1824 1828 1832 1836 1840 1844 1848 1852 1856 1860 18...

Not to be confused with Mira Monte High School. Public high school in Orinda, California, United StatesMiramonte High SchoolMatador InsigniaAddress750 Moraga WayOrinda, CaliforniaUnited StatesCoordinates37°50′26″N 122°08′46″W / 37.8404819°N 122.1460766°W / 37.8404819; -122.1460766[1]InformationTypePublic high schoolEstablished1955; 69 years ago (1955)CEEB code052282PrincipalBen CampopianoEnrollment1,174 (2020–21)[2]Color...

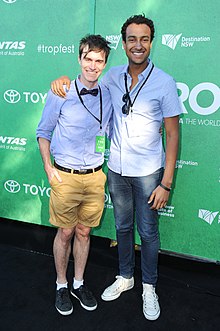

Australian radio presenter Alex DysonDyson (left) with co-host Matt Okine at Tropfest Australia in 2013BornAlexander Edward Dyson (1988-06-22) 22 June 1988 (age 35)Warrnambool, Victoria, AustraliaAlma materUniversity of MelbournePolitical partyIndependentPresenting careerStationTriple JCountryAustralia Alexander Edward Dyson (born 22 June 1988) is an Australian radio presenter who presented the breakfast show on Australian youth radio station Triple J from 2010 to 2016, alongside To...

Central Bank of Vatican City Part of a series on theRoman Curia Secretariat of State Section for Relations with States Dicasteries Evangelization Doctrine of the Faith Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors International Theological Commission Pontifical Biblical Commission Service of Charity Eastern Churches Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments Causes of Saints Bishops Pontifical Commission for Latin America Clergy Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Aposto...

Former U.S. House district in Pennsylvania Pennsylvania's 19th congressional districtObsolete districtCreated1830Eliminated2010Years active1833-2013 Pennsylvania's 19th congressional district was a congressional district that became obsolete for the 113th Congress in 2013, due to Pennsylvania's slower population growth compared to the rest of the nation. In its last incarnation, the district included all of Adams and York Counties, and parts of Cumberland County. The last representative was R...

River in Florida, United States of America The Steinhatchee River is a short river in the Big Bend region of Florida in the United States. The river rises in the Mallory Swamp just south of Mayo in Lafayette County and flows for 34.5 miles (55.5 km)[1] out of Lafayette County, forming the boundary between Dixie County and Taylor County to the Gulf of Mexico. It has a drainage basin of 586 square miles (1,520 km2). The river has also been known as the Hittenhatchee, Esteenhat...

この項目には、一部のコンピュータや閲覧ソフトで表示できない文字が含まれています(詳細)。 数字の大字(だいじ)は、漢数字の一種。通常用いる単純な字形の漢数字(小字)の代わりに同じ音の別の漢字を用いるものである。 概要 壱万円日本銀行券(「壱」が大字) 弐千円日本銀行券(「弐」が大字) 漢数字には「一」「二」「三」と続く小字と、「壱」「�...

Bassin de LondresPrésentationType Bassin sédimentaireLocalisationLocalisation Royaume-UniCoordonnées 51° 45′ 50″ N, 0° 26′ 42″ Emodifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata Carte géologique du Sud-Est de l’Angleterre et des régions environnant la Manche, montrant le bassin de Londres et ses environs. Le bassin de Londres est un bassin allongé, grossièrement triangulaire d'environ 250 km de long sur lequel se trouve Londres et une ...

Six U.S. Army enlisted men courts-martialed for refusing orders to Vietnam in June 1970 The Fort Lewis Six arrested in June 1970 for refusing orders to Vietnam. The Fort Lewis Six were six U.S. Army enlisted men at the Fort Lewis Army base in the Seattle and Tacoma, Washington area who in June 1970 refused orders to the Vietnam War and were then courts-martialed.[1] They had all applied for conscientious objector status and been turned down by the Pentagon. The Army then ordered them ...

坐标:43°11′38″N 71°34′21″W / 43.1938516°N 71.5723953°W / 43.1938516; -71.5723953 此條目需要补充更多来源。 (2017年5月21日)请协助補充多方面可靠来源以改善这篇条目,无法查证的内容可能會因為异议提出而被移除。致使用者:请搜索一下条目的标题(来源搜索:新罕布什尔州 — 网页、新闻、书籍、学术、图像),以检查网络上是否存在该主题的更多可靠来源...

斯洛博丹·米洛舍维奇Слободан МилошевићSlobodan Milošević 南斯拉夫联盟共和国第3任总统任期1997年7月23日—2000年10月7日总理拉多耶·孔蒂奇莫米尔·布拉托维奇前任佐兰·利利奇(英语:Zoran Lilić)继任沃伊斯拉夫·科什图尼察第1任塞尔维亚总统任期1991年1月11日[注]—1997年7月23日总理德拉古京·泽莱诺维奇(英语:Dragutin Zelenović)拉多曼·博若维奇(英语:Radoman Bo...

Kepulauan SolomonKepulauan Solomon, yang terdiri dari negara Kepulauan Solomon dan daerah Bougainville (bagian dari Papua Nugini). (Tekan untuk memperbesar)GeografiLokasiPasifik SelatanPulau besarBougainville, GuadalcanalPemerintahanNegara Papua Nugini Kepulauan Solomon Kepulauan Solomon merupakan sebuah kepulauan barat Samudra Pasifik, terletak di sebelah timur laut Australia. Kepulauan Solomon termasuk ke dalam kawasan Oseania. Bagian barat lautnya masuk ke dalam Wilayah Otonomi B...

Фермион Состав может быть как фундаментальной частицей, так и составной (в т.ч. квазичастицей) Классификация для фундаментальных фермионов: кварки и лептоны. Для элементарных частиц: лептоны и барионы Участвует во взаимодействиях Гравитационное, слабое [1] (общее для ...

American professional wrestler Delmi ExoBirth nameElizabeth MedranoBorn (1996-04-16) April 16, 1996 (age 28)Providence, Rhode Island, U.S.Professional wrestling careerRing name(s)Delmi ExoBilled height5 ft 7 in (170 cm)Billed weight134 lb (61 kg)Trained byDoug SummersDebutMay 2, 2015 Elizabeth Medrano (born April 16, 1996), known under the ring name Delmi Exo, is an American professional wrestler and promoter. She is currently signed to Major League Wrestling whe...

Art museum in Place Yves Klein - Nice cedex FRANCEMusée d'art moderne et d'art contemporainLocation within NiceEstablished21 June 1990 (1990-06-21)LocationPlace Yves Klein - 06364 Nice cedex 4 FRANCECoordinates43°42′05″N 7°16′43″E / 43.7014°N 7.2785°E / 43.7014; 7.2785TypeArt museumVisitors135714 per year (2012)Websitewww.mamac-nice.orgThe MAMAC is closed as of Jan 2024 for four years of renovations. [1] The Musée d'art moderne et d...

Open sided, thatched roof, native shelter, Everglades, FL, US Mother and children at a camp on the Brighton Seminole Indian Reservation, 1949 An Indian camp with a sleep chickee, cooking chickee, and eating chickee Chikee or Chickee (house in the Creek and Mikasuki languages spoken by the Seminoles and Miccosukees) is a shelter supported by posts, with a raised floor, a thatched roof and open sides. Chickees are also known as chickee huts, stilt houses, or platform dwellings. The chickee styl...

1997 video game 1997 video game7th LegionNorth American cover artDeveloper(s)Epic MegaGamesVision SoftwarePublisher(s)MicroProseProducer(s)Robert A. AllenMichael MancusoProgrammer(s)Paul AndrewsArtist(s)Rodney SmithGrant WallisComposer(s)Blair ZuppicichPlatform(s)Microsoft WindowsReleaseSeptember 24, 1997[1]Genre(s)Real-time strategyMode(s)Single-player, multiplayer 7th Legion is a real-time strategy video game for Microsoft Windows, developed by Vision Software and Epic MegaGames and...