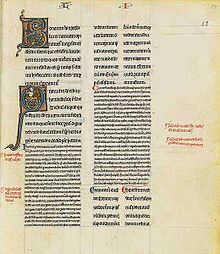

Condemnations of 1210–1277

|

Read other articles:

Sayap Cinta TerindahGenre Drama Keluarga Roman SkenarioAviv ElhamSutradaraKiky ZkrPemeran Rayn Wijaya Jeff Smith Sandy Pradana Davina Karamoy Devi Permatasari Nicole Parham Aditya Suryo Randy Martin Josephine Firmstone Dinda Annisa Mala Barbie Penggubah lagu temaAhmad DhaniLagu pembukaSatu — Dewa 19Lagu penutupSatu — Dewa 19Penata musikJoseph S DjafarNegara asalIndonesiaBahasa asliBahasa IndonesiaJmlh. musim1Jmlh. episode38ProduksiProduser eksekutif Filriady Kusmara Rista Ferina And...

Sampul CD single I Turn To You I Turn To You adalah single ketiga dari album Christina Aguilera. I Turn To You merupakan lagu re-cover yang pernah dipopulerkan oleh R. Kelly sebagai soundtrack untuk film animasi Space Jam. Penggarapan video tersebut disutradarai oleh Rupert C. Almond dan dibuat dalam 2 versi, yaitu versi internasional dan versi latin dengan judul Por Siempre Tu. Single tersebut kurang begitu sukses dibanding dengan 2 single sebelumnya yaitu Genie In A Bottle dan What A Girl W...

Soothing children's song For other uses, see Lullaby (disambiguation). Cradle song redirects here. For other uses, see Cradle Song (disambiguation). Lullaby by François Nicholas Riss [fr] A lullaby (/ˈlʌləbaɪ/), or a cradle song, is a soothing song or piece of music that is usually played for (or sung to) children (for adults see music and sleep). The purposes of lullabies vary. In some societies they are used to pass down cultural knowledge or tradition. In addition, lullab...

Australian islands in the Indian Ocean Cocos Islands redirects here. For other uses, see Cocos Islands (disambiguation). Place in AustraliaCocos (Keeling) IslandsAustralian Indian Ocean TerritoryExternal territory of AustraliaTerritory of Cocos (Keeling) IslandsPulu Kokos (Keeling) (Cocos Islands Malay)Wilayah Kepulauan Cocos (Keeling) (Malay) FlagMotto: Maju Pulu Kita (Cocos Islands Malay)(English: Onward our island)Anthem: Advance Australia FairLocation of the Cocos (Kee...

هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالات أخرى قليلة جدًا. فضلًا، ساعد بإضافة وصلة إليها في مقالات متعلقة بها. (سبتمبر 2015) يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها...

TosariDesaNegara IndonesiaProvinsiJawa TimurKabupatenPasuruanKecamatanTosariKode pos67177Kode Kemendagri35.14.24.2004 Luas... km²Jumlah penduduk... jiwaKepadatan... jiwa/km² Tosari di akhir abad ke-19 Tosari adalah sebuah desa di wilayah Kecamatan Tosari, Kabupaten Pasuruan, Provinsi Jawa Timur. Referensi (Indonesia) Keputusan Menteri Dalam Negeri Nomor 050-145 Tahun 2022 tentang Pemberian dan Pemutakhiran Kode, Data Wilayah Administrasi Pemerintahan, dan Pulau tahun 2021 (Indonesia) P...

Si ce bandeau n'est plus pertinent, retirez-le. Cliquez ici pour en savoir plus. Cet article ne cite pas suffisamment ses sources (juillet 2020). Si vous disposez d'ouvrages ou d'articles de référence ou si vous connaissez des sites web de qualité traitant du thème abordé ici, merci de compléter l'article en donnant les références utiles à sa vérifiabilité et en les liant à la section « Notes et références » En pratique : Quelles sources sont attendues ? Co...

Japanese baseball player Baseball player Takehiro IshikawaIshikawa with the Yokohama DeNA BayStarsFree Agent InfielderBorn: (1986-07-10) July 10, 1986 (age 37)Suntō District, Shizuoka, JapanBats: LeftThrows: RightNPB debutOctober 12, 2006, for the Yokohama BayStarsCareer statistics (through 2020 season)Batting average.256Home runs23Runs batted in224 Teams Yokohama BayStars/Yokohama DeNA BayStars (2005–2020) Takehiro Ishikawa (石川 雄洋, Ishikawa Takehiro, born July ...

Guru Sohalompoan Sibagariang adalah generasi ke-4 dalam silsilah garis keturunan marga Sibagariang. Keturunan Donda Hopol Artikel utama: SibagariangDonda Hopol merupakan generasi pertama marga Sibagariang, selanjutnya anak Donda Hopol dihitung sebagai generasi kedua, cucu Donda Hopol sebagai generasi ketiga dan demikian seterusnya. Penyebutan nomor generasi ini sering dilakukan ketika sesama keturunan Donda Hopol bertemu untuk mengetahui letak hubungan kekerabatan dalam silsilah. Diperkirakan...

Niemcy Ten artykuł jest częścią serii:Ustrój i politykaNiemiec Ustrój polityczny Ustrój polityczny Niemiec Konstytucja Konstytucja Niemiec Władza ustawodawcza Bundestag Przewodniczący: Bundesrat Przewodniczący: Władza wykonawcza Prezydent federalny Kanclerz federalny Rząd federalny Niemiec Władza sądownicza System prawny Federalny Trybunał Konstytucyjny Federalny Trybunał Sprawiedliwości Federalny Sąd Administracyjny Federalny Sąd Pracy Federalny Trybunał Finansowy Prokura...

Programma delle Nazioni Unite per gli insediamenti umani(EN) United Nations Human Settlements Programme(FR) Programme des Nations unies pour les établissements humains(ES) Programa de Naciones Unidas para los Asentamientos Humanos Bandiera del Programma per gli Insediamenti Umani AbbreviazioneUN-HABITAT Tipoagenzia dell'Organizzazione delle Nazioni Unite Fondazione1978 Scopopromozione di un'urbanizzazione socialmente ed ambientalmente sostenibile Sede centrale Nairobi Area di azione129 Stati...

Placeholder text used in publishing and graphic design Ipsum redirects here. For the car, see Toyota Ipsum. Using Lorem ipsum to focus attention on graphic elements in a webpage design proposal One of the earliest examples of the Lorem ipsum placeholder text on 1960s advertising In publishing and graphic design, Lorem ipsum (/ˌlɔː.rəm ˈɪp.səm/) is a placeholder text commonly used to demonstrate the visual form of a document or a typeface without relying on meaningful content. Lorem ips...

University in Makhanda, South Africa Rhodes UniversityCoat of armsFormer namesRhodes University CollegeMottoWhere leaders learnTypePublicEstablished31 May 1904; 119 years ago (1904-05-31)EndowmentR429.6 million[1] (US$59.853 million as of 2008[update])ChancellorLex MpatiVice-ChancellorSizwe MabizelaAcademic staff357[2]Students7,005[2]Undergraduates5,372[2]Postgraduates1,633[2]LocationMakhanda, Eastern Cape, South Africa33°18�...

Resolusi 1432Dewan Keamanan PBBCitra satelit AngolaTanggal15 Agustus 2002Sidang no.4,603KodeS/RES/1432 (Dokumen)TopikSituasi di AngolaRingkasan hasil15 mendukungTidak ada menentangTidak ada abstainHasilDiadopsiKomposisi Dewan KeamananAnggota tetap Tiongkok Prancis Rusia Britania Raya Amerika SerikatAnggota tidak tetap Bulgaria Kamerun Kolombia Guinea Irlandia Meksiko Mauritius Norwegia Singapura Syria Resolus...

State Highway 4Route informationLength466 km (290 mi)Major junctionsFromSH 4A at JhaldaMajor intersections NH 18 at Balarampur SH 5 at Manbazar SH 2 from Hatirampur to Khatra SH 9 from Raipur Bazar to Pirolgari more NH 14 at Chandrakona Road SH 7 from Chandrakona to Khirpai NH 16 at Panskura NH 116 at Nandakumar Chandipur-Nandigram Road at Math Chandipur Egra-Bhagabanpur-Bajkul Road at Bajkul Lalat-Janka Road at Henria SH 5 at Contai Egra-Ramnagar Road at Ramnagar ToSH 57 (Odis...

Bastian StegerPersonal informationKebangsaanjERMANLahir19 Maret 1981 (umur 42)Oberviechtach, jERMANGaya bermainRight-handed, shakehand gripEquipment(s)Butterfly Innerforce Layer ZLF blade; Butterfly Tenergy 05 (Red, FH), Butterfly Tenergy 05 (Black, BH)Peringkat tertinggi18 (OKtober 2014)Peringkat sekarang35 (Agustus 2018)Tinggi1.70 mBerat65 kg Rekam medali Putra tenis meja Mewakili Jerman Olimpiade 2012 London Team 2016 Rio de Janeiro Team World Championships 2018 Halmstad Team Eu...

Biathlon World Championships 1970Host cityÖstersundCountrySwedenEvents2Opening1 February 1970 (1970-02-01)Closing9 February 1970 (1970-02-09)Main venueÖstersund Ski Stadium← Zakopane 1969Hämeenlinna 1971 → The 10th Biathlon World Championships were held in Östersund, Sweden in February 1970.[1] Men's results 20 km individual Medal Name Nation Penalties Result Alexander Tikhonov URS 5 1:22:46.2 Tor Svendsberget NOR 3 1...

Doreen BraitlingDoreen BraitlingPersonal detailsBornDoreen Rose Crook1904Colchester, EnglandDied2 February 1979(1979-02-02) (aged 74–75)Alice Springs, AustraliaNationalityAustralianSpouseWilliam BraitlingChildrenWilliamOccupationPastoralist and Advocate Doreen Rose Braitling (nee Crook) (1904 – 5 February 1979) was a pioneering pastoralist and heritage advocate of Central Australia. After moving from Mount Doreen Station to Alice Springs in 1959, Braitling became involved in the ...

River in Idaho, United StatesSelway RiverSelway River at the Goat Creek rapidCourse of the riverLocation of the mouth of the Selway River in IdahoShow map of IdahoSelway River (the United States)Show map of the United StatesLocationCountryUnited StatesStateIdahoCountyIdahoPhysical characteristicsSourceSoutheast of Stripe Mountain • locationBitterroot National Forest, Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, Bitterroot Mountains • coordinates45°29′49″N 114°44′...

Герої Соціалістичної Праці, починаючи з літери Т: До списку не включено осіб, удостоєних двох і більше медалей «Серп і Молот». Табачний Геннадій Матвійович Тазеєва Міннесагіра Тазеївна Таїров Сеїт Меметович Тамм Ігор Євгенович Танк Максим Танченко Степан Дмитрович Тара...