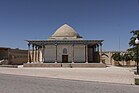

Shahrisabz

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Artikel atau sebagian dari artikel ini mungkin diterjemahkan dari Dino Zoff di en.wikipedia.org. Isinya masih belum akurat, karena bagian yang diterjemahkan masih perlu diperhalus dan disempurnakan. Jika Anda menguasai bahasa aslinya, harap pertimbangkan untuk menelusuri referensinya dan menyempurnakan terjemahan ini. Anda juga dapat ikut bergotong royong pada ProyekWiki Perbaikan Terjemahan. (Pesan ini dapat dihapus jika terjemahan dirasa sudah cukup tepat. Lihat pula: panduan penerjemahan a...

Gubernur Negara Bagian OhioLambang Gubernur OhioBendera standar Gubernur OhioPetahanaMike DeWinesejak 14 Januari 2019GelarThe HonorableKediamanMansion Gubernur OhioMasa jabatan4 tahun, bisa menjabat lagi sekali, lalu bisa menjabat lagi dengan jeda minimal 4 tahunPejabat perdanaEdward TiffinDibentuk3 Maret 1803WakilWakil Gubernur OhioGaji$148,886 (2015)[1] Halaman ini memuat daftar gubernur negara bagian Ohio, Amerika Serikat Gubernur Wilayah (Northwest Territory) Mulai Menjabat A...

Shopping mall in LondonSurrey Quays Shopping CentreLocationLondonAddressSurrey Quays, Redriff RoadOpening dateJuly 1988; 35 years ago (1988-07)[1]ManagementSurrey Quays Limited[2]OwnerBritish Land[3]No. of stores and services43Total retail floor area309,000 square feet (28,700 m2)[2]No. of floors2Parking650[4]Public transit accessCanada Water stationSurrey Quays stationWebsitewww.surreyquays.co.uk Surrey Quays Shopping Centr...

SMK Negeri 4 PadangInformasiDidirikan25 September 1965JenisNegeriAkreditasiBNomor Statistik Sekolah401086103006Nomor Pokok Sekolah Nasional10304850Kepala SekolahSahfalefi, S.Pd., M.Pd.[1]Rentang kelasX, XI, XII, XIII (Desain Interioir)KurikulumKurikulum 2013AlamatLokasiCengkeh Nan XX, Lubuk Begalung, Padang, Sumatera Barat, IndonesiaTel./Faks.0751-71654Situs webhttps://smk4-padang.sch.id/[email protected] untuk Orang Kreatif SMK Negeri 4 Padang adalah ...

Jang WooyoungInformasi latar belakangNama lahirJang Wooyoung (Hangul: 우영)Lahir30 April 1989 (umur 34)Busan, Korea SelatanPekerjaanPenyanyi,[1] Penari,[1] AktorTahun aktif2008–sekarangArtis terkait2PMSitus webhttp://jangwooyoung.jype.com/ Korean nameHangul장우영 Hanja張佑榮 Alih AksaraJang Wooyoung Jang Wooyoung dikenal juga sebagai Wooyoung (Hangul: 우영; lahir 30 April 1989) adalah penyanyi di 2PM. Selain penyanyi ia juga merupakan seorang aktor dan penari....

American film distributor Not to be confused with Magnolia (film). Magnolia PicturesCompany typeSubsidiaryIndustryMotion picturesFounded2001; 23 years ago (2001)FoundersBill Banowsky Eamonn BowlesHeadquartersNew York City, New York, United StatesParent2929 EntertainmentSubsidiariesMagnolia Home EntertainmentMagnet ReleasingMagnifyWebsitemagnoliapictures.com Magnolia Pictures is an American film distributor and production company, and is a subsidiary of Mark Cuban and Todd Wa...

Hazard symbol used by emergency personnel to identify the risks posed by hazardous materials NFPA 704fire diamond 4 4 4WThis article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: NFPA 704 – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)NFPA 704 sa...

Seitenkyū, sebuah kuil Tao di Sakado, Saitama. Taoisme diyakini menjadi inspirasi bagi konsep spiritual dalam budaya Jepang.[butuh rujukan] Taoisme mirip dengan Shinto dalam hal itu juga dimulai sebagai agama asli di Tiongkok, meskipun lebih hermetis daripada perdukunan. Pengaruh Taoisme dapat dilihat di seluruh budaya tetapi pada tingkat yang lebih rendah daripada Konfusianisme. Taoisme dalam bentuk yang diambil di Jepang dapat dengan mudah dilihat sebagai takhayul atau astrologi da...

本條目存在以下問題,請協助改善本條目或在討論頁針對議題發表看法。 此條目需要編修,以確保文法、用詞、语气、格式、標點等使用恰当。 (2013年8月6日)請按照校對指引,幫助编辑這個條目。(幫助、討論) 此條目剧情、虛構用語或人物介紹过长过细,需清理无关故事主轴的细节、用語和角色介紹。 (2020年10月6日)劇情、用語和人物介紹都只是用於了解故事主軸,輔助�...

Частина серії проФілософіяLeft to right: Plato, Kant, Nietzsche, Buddha, Confucius, AverroesПлатонКантНіцшеБуддаКонфуційАверроес Філософи Епістемологи Естетики Етики Логіки Метафізики Соціально-політичні філософи Традиції Аналітична Арістотелівська Африканська Близькосхідна іранська Буддій�...

American politician For other people named Alexander Clay, see Alexander Clay (disambiguation). Alexander S. ClayUnited States Senatorfrom GeorgiaIn officeMarch 4, 1897 – November 13, 1910Preceded byJohn B. GordonSucceeded byJoseph M. TerrellMember of the Georgia House of RepresentativesIn office1884-18871889-1890 Personal detailsBornAlexander Stephens Clay(1853-09-25)September 25, 1853Powder Springs, GeorgiaDiedNovember 13, 1910(1910-11-13) (aged 57)Atlanta, GeorgiaPolitical ...

Country in South America This article is about the country. For other uses, see Paraguay (disambiguation). Republic of ParaguayRepública del Paraguay (Spanish)Paraguái Tavakuairetã (Guarani) Flag [b] Seal [a] Motto: Paz y justicia (Spanish)Peace and justiceAnthem: Himno Nacional Paraguayo (Spanish)Paraguayan National AnthemLocation of Paraguay (dark green)in South America (grey)Capitaland largest cityAsunción25°16�...

Abdul Aziz Ali Wafa Anggota Konstituante Republik IndonesiaMasa jabatan9 November 1956 – 5 Juli 1959PresidenSoekarno Informasi pribadiLahir1 Januari 1900Pamekasan, Jawa TimurMeninggal1962(umur 62)Partai politik MasyumiSunting kotak info • L • B Abdul Aziz Ali Wafa (lahir 1 Januari 1900 – 1962) adalah seorang politikus, pendiri, pengasuh pesantren Bustanul Ulum, ketua KNI, dan penjaga keamanan daerah asal Indonesia.[1] Ia merupakan anggota partai Masyumi dan ...

1978 studio album by WhitesnakeTroubleOriginal UK sleeveStudio album by WhitesnakeReleasedOctober 1978[1]RecordedJuly–August 1978 [2]StudioCentral Recorders (London)GenreHard rockblues rockLength38:20LabelEMI International (UK)Harvest/Sunburst (Europe)United Artists/Sunburst (North America)Polydor (Japan)ProducerMartin BirchWhitesnake chronology Snakebite(1978) Trouble(1978) Lovehunter(1979) Alternative coverLP and CD cover Singles from Trouble Lie Down (A Modern Lo...

伊索拉·蒂比斯摄于2013年世锦赛個人資料代表國家/地區 法國出生 (1991-08-22) 1991年8月22日(32歲) 法國瓜德罗普莱萨比姆項目花剑身高1.74米(5英尺9英寸)體重56公斤(123磅) 奖牌记录 女子花剑 代表 法國 奥林匹克运动会 2020 东京 团体花剑 世界擊劍錦標賽 2022 开罗 个人花剑 2013 布达佩斯 团体花剑 2018 无锡 个人花剑 2023 米兰 团体花剑 2014 喀山 团体花剑 2015 莫斯...

Malaysian beach For the dredger, see SS Morib. This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Morib – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Morib in Kuala Langat District Morib is a mukim in Kuala Langat District, Selangor, Malaysia, under the ad...

Selección de fútbol de Italia Datos generalesPaís ItaliaCódigo FIFA ITAFederación FIGCConfederación UEFASeudónimo(s) Gli Azzurri (Los Azules)La Nazionale (El Equipo Nacional)Seleccionador Luciano Spalletti (desde 2023)Capitán Gianluigi DonnarummaMás goles Luigi Riva (35)Más partidos Gianluigi Buffon (176)Clasificación FIFA 10.º (julio de 2024)Títulos ganados 7Finales jugadas 12Estadio(s) Giuseppe Meazza, MilánOlímpico, RomaEquipaciones Primera Segunda Primer partido Itali...

MongolPoster bioskopSutradaraSergei BodrovProduserSergei SelyanovSergei BodrovAnton MelnikDitulis olehArif AliyevSergei BodrovPemeranTadanobu AsanoSun HongleiKhulan ChuluunOdnyam OdsurenPenata musikTuomas KantelinenSinematograferSergey TrofimovRogier StoffersDistributorPicturehouseTanggal rilis 20 September 2007Durasi120 menitNegara Jerman Kazakhstan Rusia MongoliaBahasaMongoliaAnggaranUS$10.000.000 (perkiraan) Mongol (bahasa Mongol: Монгол кино; bahasa Rus...

Amedeo CarboniCarboni nel 2005Nazionalità Italia Altezza180 cm Peso73 kg Calcio RuoloDifensore Termine carriera2006 CarrieraGiovanili 1975-1983 Arezzo1983-1984 Fiorentina Squadre di club1 1984-1985 Arezzo22 (1)1985-1986→ Bari10 (0)1986-1987 Empoli11 (0)1987-1988 Parma28 (1)1988-1990 Sampdoria60 (2)1990-1997 Roma186 (3)1997-2006 Valencia245 (1) Nazionale 1988 Italia U-211 (1)1991-1997 Italia18 (0) 1 I due numeri indicano le presenze e le re...

Leang Samongkeng IGua Samongkeng I, Gua Samungkeng I, Gua Samongkeng 1, Gua Samungkeng 1Lua error in Modul:Location_map at line 423: Kesalahan format nilai koordinat.LokasiKampung Bonto Labbu, Lingkungan Leang-Leang, Kelurahan Leang-Leang, Kecamatan Bantimurung, Kabupaten Maros, Sulawesi Selatan, IndonesiaKoordinat04°58'49.2S 119°39'52.5E[1]Geologikarst / batu kapur / batu gampingSitus webvisit.maroskab.go.idcagarbudaya.kemdikbud.go.idkebudayaan.kemdikbud.go.id/bpcbsulsel/ Wisata Gu...