Sechs kleine Klavierstücke

|

Read other articles:

Jung Hye-youngLahir14 Desember 1973 (umur 50)PekerjaanArtisTahun aktif1993-sekarangSuami/istriSean Noh Jung Hye-young (lahir 14 Desember 1973) adalah seorang aktris asal Korea Selatan. Kehidupan pribadi Dia menikah dengan Sean Noh, Sean Jung Hye-young berkomitmen untuk beramal sebagai anggota Hiburan YG duet hiphop: Jinusean dan memiliki seorang putri dan dua putra. Drama Teacher, 1993 You are so Nice, 1995 Jazz, SBS 1996 Starting to Happy, 1997 My Lady, KBS 1997 Mr. Right, KBS2 19...

Playboy IndonesiaPlayboy Indonesia edisi perdana dengan model sampul Andhara Early.Mantan Pemimpin RedaksiErwin ArnadaKategoriMajalah pria dewasaFrekuensiBulananPenerbitPT Velvet Silver MediaPendiriErwin ArnadaTerbitan pertamaApril 2006Terbitan terakhirAngkaMaret 200711Negara IndonesiaBerpusat diJakartaBali (sejak edisi ke-2)BahasaIndonesia Playboy Indonesia adalah edisi majalah Playboy dalam bahasa Indonesia. Edisi perdananya terbit pada bulan 7 April 2006 dan ditutup pada Maret 2007. &...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir PPM. Un 'squitter' 1090ES de 56 bits utilisé en aviation civile. La modulation d'impulsions en position (MIP) (en anglais : pulse-position modulation (PPM)), est une technique de modulation utilisée pour transmettre sur une liaison « point-à-point » un symbole de M bits en une seule impulsion codée parmi un alphabet de 2 M {\displaystyle 2^{M}} transitions possibles dans le temps. Ceci est répété chaque T secondes, ce qui permet d'att...

Engineering association based in London This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article contains content that is written like an advertisement. Please help improve it by removing promotional content and inappropriate external links, and by adding encyclopedic content written from a neutral point of view. (June 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) This ar...

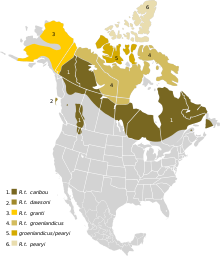

Subspecies of deer Peary caribou Peary caribou Conservation status Endangered (IUCN 3.1)[1] Imperiled (NatureServe)[2] Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Artiodactyla Family: Cervidae Subfamily: Capreolinae Genus: Rangifer Species: R. arcticus Subspecies: R. a. pearyi Trinomial name Rangifer arcticus pearyi(Allen, 1902) Approximate range of Peary caribou. Overlap with other subspecies of c...

Questa voce o sezione sugli argomenti istruzione e cattolicesimo è priva o carente di note e riferimenti bibliografici puntuali. Sebbene vi siano una bibliografia e/o dei collegamenti esterni, manca la contestualizzazione delle fonti con note a piè di pagina o altri riferimenti precisi che indichino puntualmente la provenienza delle informazioni. Puoi migliorare questa voce citando le fonti più precisamente. Segui i suggerimenti dei progetti di riferimento 1, 2. Pontificio istituto o...

This article is about the chemical element. For other uses, see Osmium (disambiguation). Chemical element, symbol Os and atomic number 76Osmium, 76OsOsmiumPronunciation/ˈɒzmiəm/ (OZ-mee-əm)Appearancesilvery, blue castStandard atomic weight Ar°(Os)190.23±0.03[1]190.23±0.03 (abridged)[2] Osmium in the periodic table Hydrogen Helium Lithium Beryllium Boron Carbon Nitrogen Oxygen Fluorine Neon Sodium Magnesium Aluminium Silicon Phosphorus Sulfur Ch...

1994 video by Iron MaidenRaising HellVideo by Iron MaidenReleased5 September 1994 (1994-09-05)Recorded28 August 1993[1]VenuePinewood Studios, LondonGenreHeavy metalLength113:00 (approx.)LabelPMIDirectorDeclan LowneyProducerMichael PillotIron Maiden chronology Donington Live 1992(1993) Raising Hell(1994) Classic Albums: Iron Maiden – The Number of the Beast(2001) Raising Hell is a concert video by the heavy metal band Iron Maiden, filmed on 28 August 1993 at t...

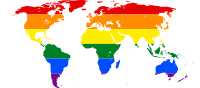

Флаг гордости бисексуалов Бисексуальность Сексуальные ориентации Бисексуальность Пансексуальность Полисексуальность Моносексуальность Сексуальные идентичности Би-любопытство Гетерогибкость и гомогибкость Сексуальная текучесть Исследования Шк...

الأوضاع القانونية لزواج المثليين زواج المثليين يتم الاعتراف به وعقده هولندا1 بلجيكا إسبانبا كندا جنوب أفريقيا النرويج السويد المكسيك البرتغال آيسلندا الأرجنتين الدنمارك البرازيل فرنسا الأوروغواي نيوزيلندا3 المملكة المتحدة4 لوكسمبورغ الولايات المتحدة5 جمهورية أيرلندا ...

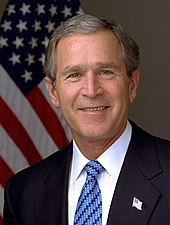

This list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. (July 2014) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: 2005 in the United States – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message)List of events ← 2004 2003 2002 2005 in the United Sta...

توني كاسكارينو كاسكارينو عام 1986 معلومات شخصية الاسم الكامل أنتوني غاي كاسكارينو الميلاد 1 سبتمبر 1962 (العمر 61 سنة)سينت باولز كراي, كينت, إنجلترا الطول 1.91 م (6 قدم 3 بوصة) مركز اللعب مهاجم الجنسية جمهورية أيرلندا المسيرة الاحترافية1 سنوات فريق م. (هـ.) 1980–1981 كروكنهل 19...

باتلفيلد 2142Battlefield 2142 (بالإنجليزية: Battlefield 2142) المطور ديجيتال إلوجينز سي إي الناشر إلكترونيك آرتس سلسلة اللعبة باتلفيلد محرك اللعبة ريفراكتور إنجين 2 النظام مايكروسوفت ويندوز ماك أو إس عشرة تاریخ الإصدار 17 أكتوبر 2006 (أمريكا الشمالية)18 أكتوبر 2006 (أسترالاسيا)20 أكتوبر 2006 (�...

Desert in South Australia Tirari DesertNASA satellite image, 2006This is a map of the Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation of Australia (IBRA), with state boundaries overlaid. The Tirari Desert region is shown in red.Area15,250 km2 (5,890 sq mi)GeographyCountryAustraliaStateSouth AustraliaRegionFar NorthCoordinates28°22′S 138°07′E / 28.37°S 138.12°E / -28.37; 138.12 The Tirari Desert is a 15,250 square kilometres (5,888 sq mi)&#...

Anna NahirnaAnna Nahirna au championnat d'Europe sur piste 2017InformationsNaissance 30 septembre 1988 (35 ans)UkraineNationalité ukrainienneÉquipe actuelle Lviv Cycling TeamÉquipe UCI 2019-Lviv Cycling Teammodifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata Anna Nahirna (née le 30 septembre 1988 à Lviv) est une coureuse cycliste ukrainienne. Palmarès sur piste Championnats du monde Apeldoorn 2013 7e de la poursuite 10e de la poursuite par équipes Hong Kong 2017 16e de la course aux p...

International sporting eventMen's 200 metre breaststroke at the 2019 Pan American GamesVenueVilla Deportiva Nacional, VIDENADatesAugust 8 (preliminaries and finals)Competitors24 from 19 nationsWinning time2:07.62Medalists Will Licon United States Nic Fink United States Miguel de Lara Mexico«2015 2023» International sporting eventSwimming at the2019 Pan American GamesQualificationFreestyle50 mmenwomen100 mmenwomen200 mmenwomen400...

507-й окремий навчальний ремонтно-відновлювальний батальйонНарукавний знакНа службіз 1957 — по сьогодніКраїнаУкраїнаВидСухопутні війська УкраїниТипЗбройні сили УкраїниРольнавчальна частинаУ складі169-й навчальний центр Сухопутних військГарнізон/ШтабДесна (Козелец�...

СтанцияКиров-КотласскийКиров — КотласГорьковская железная дорога 58°36′21″ с. ш. 49°38′38″ в. д.HGЯO Регион ж. д. Кировский регион Дата открытия 1899 год[1] Прежние названия Вятка, Вятка-II (до 1934)[2], Вятка-Пермская, Вятка-Котласская Количество платформ 1 Количест...

Liste des députés de la Loire Article connexe : Liste des circonscriptions législatives de la Loire. Avant la Seconde République Joseph Alcock Jacques Ardaillon Pierre d'Assier de Valenches Claude-Philibert Barthelot de Rambuteau Damien Battaut de Pomérol Jean-Jacques Baude Jean-Pierre Bruyas Jean de Chantelauze Jean-Claude Chovet de la Chance Antoine Conte Antoine Courbon-Saint-Genest Tristan Duché Alphonse Dumarais Michon Antoine Dugas des Varennes André Duguet Jean Durosier Jea...

Advanced airway managementAn anesthesiologist using a video laryngoscope to intubate a patient with challenging airway anatomy[edit on Wikidata] Advanced airway management is the subset of airway management that involves advanced training, skill, and invasiveness. It encompasses various techniques performed to create an open or patent airway – a clear path between a patient's lungs and the outside world. This is accomplished by clearing or preventing obstructions of airways. There are m...