Dynamic method

|

Read other articles:

Kishiryu Sentai RyusoulgerGenreTokusatsu, Drama, Aksi, KomediPembuatTV AsahiToei CompanyBandai VisualDitulis olehJunpei YamaokaAyumi ShimoKaori KanekoNaruhisa ArakawaHiroya TakaSutradaraKazuya KamihoriuchiShōjirō NakazawaKatsuya WatanabeKoichi SakamotoHiroki KashiwagiHiroyuki KatōPemeranHayate IchinoseKeito TsunaIchika OsakiYuito ObaraTatsuya KishidaKatsumi HyodoSora TamakiLagu pembukaKishiryu Sentai RyusoulgerDinyanyikan oleh Tomohiro HatanoLagu penutupQue Boom! RyusoulgerDinyanyikan ole...

Bad SisterPoster teatrikalSutradaraKim Tae-kyunPemeranIvy Chen Ji Jin-hee Cheney Chen Christy Chung Qi Xi Li Xinyun HyelimTanggal rilis 28 November 2014 (2014-11-28) Durasi146 menitNegaraTiongkokBahasaMandarinPendapatankotor¥8.79 juta Bad Sister (Hanzi: 坏姐姐之拆婚联盟) adalah film komedi romantis Tiongkok tahun 2014 yang disutradarai oleh Kim Tae-kyun dan dibintangi oleh Ivy Chen, Ji Jin-hee dan Cheney Chen. Film ini dirilis pada tanggal 28 November 2014.[1][2&...

Stretches of coast that have been inundated by the sea by a relative rise in sea levels This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Submergent coastline – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) A submergent landform: the drowned riv...

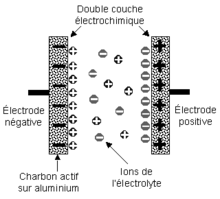

Supercondensateur Un supercondensateur est un condensateur de technique particulière permettant d'obtenir une densité de puissance et une densité d'énergie intermédiaires entre les batteries et les condensateurs électrolytiques classiques[1]. Composés de plusieurs cellules montées en série-parallèle, ils permettent une tension et un courant de sortie élevés (densité de puissance de l'ordre de plusieurs kW/kg) et stockent une quantité d'énergie intermédiaire entre les deux mode...

Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: Sanggar Bintang Sartika – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR Bintang Sartika merupakan salah satu sanggar yang masih aktif dan berada di Jakarta. Sanggar Bintang Sartika ini terletak di Ja...

Towada-Hachimantai National Park十和田八幡平国立公園IUCN Kategori II (Taman Nasional)Oirase RiverLua error in Modul:Location_map at line 437: Tidak ada nilai yang diberikan untuk garis bujur.Towada-Hachimantai National Park in JapanLetakTōhoku, JapanLuas854 kilometer persegi (330 sq mi)Didirikan1 February 1936 Towada-Hachimantai National Park (十和田八幡平国立公園code: ja is deprecated , Towada-Hachimantai Kokuritsu Kōen) adalah taman nasional yang terdiri dari...

Yak-12 Yakovlev Yak-12 (Rusia: Як-12, juga tercantum sebagai Jak-12, NATO melaporkan nama: Creek) adalah pesawat STOL multirole ringan sayap tinggi (high wing) yang digunakan oleh Angkatan Udara Soviet, penerbangan sipil Soviet dan negara-negara lain dari tahun 1947 dan seterusnya. Yak-12 dirancang oleh tim Yakovlev untuk memenuhi kebutuhan Angkatan Udara Soviet tahun 1944 untuk pesawat penghubung dan utilitas baru, untuk menggantikan biplane Po-2. Referensi Gunston, Bill. The Osprey Encyc...

Синелобый амазон Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:ЗавропсидыКласс:Пт�...

Spy KidsSpy Kids posterSutradaraRobert RodriguezProduserElizabeth AvellanRobert RodriguezDitulis olehRobert RodriguezPemeranAntonio BanderasCarla GuginoAlexa VegaDaryl SabaraCheech MarinDanny TrejoRobert PatrickTony ShalhoubAlan CummingTeri HatcherSinematograferGuillermo NavarroPenyuntingRobert RodriguezDistributorDimension FilmsMiramax Films (DVD)Tanggal rilis30 Maret 2001 (2001-03-30)Durasi88 menitNegaraAmerika SerikatBahasaInggris, SpanyolAnggaran35 juta dolar AS (perkiraan)Pendapatan...

Mr. QueenPoster promosiNama alternatifNo Touch Princess[a]Hangul철인왕후 Hanja哲仁王后 GenreSejarahKomedi romantisFantasiPertukaran tubuhPembuatStudio DragonBerdasarkanGo Princess Gooleh Xian ChenGo Princess Gooleh Qin Shuang and Shang Menglu[1]Ditulis olehPark Gye-okChoi Ah-ilSutradaraYoon Sung-sikPemeranShin Hye-sunKim Jung-hyunNegara asalKorea SelatanBahasa asliKoreaJmlh. episode20ProduksiProduser eksekutifLee Chan-hoProduserHam Jeong-yeopKim Dong-hyunHan Kwang-hoJ...

United States historic placeGraff's MarketU.S. National Register of Historic Places Modern building on site of demolished historic structureShow map of PennsylvaniaShow map of the United StatesLocation27 N. 6th St., Indiana, PennsylvaniaCoordinates40°37′25″N 79°9′2″W / 40.62361°N 79.15056°W / 40.62361; -79.15056Area0.1 acres (0.040 ha)Built1887–1892ArchitectG.W. HeskerArchitectural styleItalianate, Cast-iron facadeNRHP reference No.800...

The HonourableDame Silvia Rose CartwrightPCNZM, DBE, QSM Gubernur Jenderal Selandia Baru ke-18Masa jabatan4 April 2001 – 4 Agustus 2006Penguasa monarkiRatu Elizabeth IIPerdana MenteriHelen ClarkPendahuluSir Michael Hardie BoysPenggantiSir Anand Satyanand Informasi pribadiLahir7 November 1943 (umur 80)Dunedin, Selandia BaruKebangsaanSelandia BaruSuami/istriPeter Cartwright CNZM QSOProfesiJudgeSunting kotak info • L • B Dame Silvia Rose Cartwright, PCNZM, DBE, QSO ...

Marathi cinema All-time 1910s 1910-1919 1920s 1920 1921 1922 1923 19241925 1926 1927 1928 1929 1930s 1930 1931 1932 1933 19341935 1936 1937 1938 1939 1940s 1940 1941 1942 1943 19441945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950s 1950 1951 1952 1953 19541955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960s 1960 1961 1962 1963 19641965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970s 1970 1971 1972 1973 19741975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980s 1980 1981 1982 1983 19841985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990s 1990 1991 1992 1993 19941995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000s 2000 2001 ...

Football tournamentArnold Clark CupOrganising bodyThe Football AssociationFounded2022; 2 years ago (2022)RegionEnglandNumber of teams4Current champions England (2nd title)Most successful team(s) England (2 titles)Websitearnoldclarkcup.com 2023 Arnold Clark Cup The Arnold Clark Cup is an invitational women's association football tournament hosted by The Football Association in England, starting in 2022.[1] It is named after car retailer Arnold Clark, who si...

Skyscraper in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Vista TowerFormer namesEmpire TowerGeneral informationTypeCommercial officesLocation182 Jalan Tun RazakKuala Lumpur, MalaysiaCoordinates3°09′43″N 101°43′12″E / 3.16194°N 101.72°E / 3.16194; 101.72Construction started1991Completed1994HeightRoof238.1 m (781 ft)Technical detailsFloor count63[1]Floor area11,000 sq ft (1,000 m2)Design and constructionArchitect(s)AedasGDP ArkitectServices engin...

Mountain in Montana, United States This article is about the mountain in Montana. For nearby Alberta community, see Chief Mountain, Alberta. This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Chief Mountain – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Chi...

2016年美國總統選舉 ← 2012 2016年11月8日 2020 → 538個選舉人團席位獲勝需270票民意調查投票率55.7%[1][2] ▲ 0.8 % 获提名人 唐納·川普 希拉莉·克林頓 政党 共和黨 民主党 家鄉州 紐約州 紐約州 竞选搭档 迈克·彭斯 蒂姆·凱恩 选举人票 304[3][4][註 1] 227[5] 胜出州/省 30 + 緬-2 20 + DC 民選得票 62,984,828[6] 65,853,514[6]...

密西西比州 哥伦布城市綽號:Possum Town哥伦布位于密西西比州的位置坐标:33°30′06″N 88°24′54″W / 33.501666666667°N 88.415°W / 33.501666666667; -88.415国家 美國州密西西比州县朗兹县始建于1821年政府 • 市长罗伯特·史密斯 (民主党)面积 • 总计22.3 平方英里(57.8 平方公里) • 陸地21.4 平方英里(55.5 平方公里) • ...

Proposed resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict Binationalism and Binational state redirect here. For uses outside the Israeli–Palestinian context, see Two Nations theory, Multinational state and Consociationalism. Part of a series onthe Israeli–Palestinian conflictIsraeli–Palestinianpeace process HistoryCamp David Accords1978Madrid Conference1991Oslo Accords1993 / 95Hebron Protocol1997Wye River Memorandum1998Sharm El Sheikh Memorandum1999Camp David Summit2000The Clinto...

Japanese theoretical physicist Hideki YukawaJunior Second Rank湯川 秀樹Yukawa in 1951Born(1907-01-23)23 January 1907Tokyo, JapanDied8 September 1981(1981-09-08) (aged 74)Kyoto, JapanCitizenshipJapanAlma materKyoto Imperial UniversityOsaka Imperial UniversitySpouseSumi YukawaChildren2Awards Nobel Prize in Physics (1949) ForMemRS (1963)[1] Lomonosov Gold Medal (1964) Scientific careerFieldsTheoretical physicsInstitutionsOsaka Imperial UniversityKyoto Imperial UniversityImp...