William Bates (physician)

| |||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Desember 2022. Alten self-portrait Mathias Joseph Alten (13 Februari 1871 – 8 Maret 1938) adalah seorang pelukis impresionis Jerman-Amerika yang aktif di Grand Rapids, Michigan.[1] Karir Lahir di Gusenburg, Jerman, Alten bekerja sebagai senim...

Pusat Pelaporan & Analisis Transaksi Keuangan PPATKGambaran umumSingkatanPPATKDasar hukum pendirianUndang-Undang Nomor 8 Tahun 2010StrukturKepalaIvan YustiavandanaKantor pusatJl Ir. Haji Juanda No.35, Kb. Klp., Gambir, Kota Jakarta Pusat, Daerah Khusus Ibukota JakartaSitus webhttp://www.ppatk.go.id/Sunting kotak info • L • BBantuan penggunaan templat ini Pusat Pelaporan dan Analisis Transaksi Keuangan (PPATK) (Inggris: Indonesian Financial Transaction Reports and Analys...

Часть серии статей о Холокосте Идеология и политика Расовая гигиена · Расовый антисемитизм · Нацистская расовая политика · Нюрнбергские расовые законы Шоа Лагеря смерти Белжец · Дахау · Майданек · Малый Тростенец · Маутхаузен ·&...

CanaanSampul edisi Amerika Utara dari versi Blu-ray yang menampilkan Alphard (kiri) dan Canaan (kanan)カナン(Kanan) Seri animeSutradaraMasahiro AndoProduserJin KawamuraJirō IshiiKei FukuraKenji HorikawaShigeru SaitōTakayuki MizutaniYasushi ŌshimaSkenarioMari OkadaMusikHikaru NanaseStudioP.A.WorksPelisensiAUS Siren VisualNA Sentai FilmworksUK MVM FilmsSaluranasliTokyo MX, TVS, CTC, tvk, KTV, THK, AT-X, Anime NetworkTayang 4 Juli 2009 – 26 September 2009Episode13 (Daftar episode) MangaP...

American army officer and politician (1791–1871) Charles Stewart ToddUnited States Ambassador to RussiaIn officeNovember 28, 1841 – January 27, 1846Preceded byChurchill C. CambrelengSucceeded byRalph I. Ingersoll11th Secretary of State of KentuckyIn office1816Preceded byMartin D. HardinSucceeded byJohn Pope Personal detailsBornCharles Stewart Todd(1791-01-22)January 22, 1791Danville, Kentucky, U.S.DiedMay 17, 1871(1871-05-17) (aged 80)Baton Rouge, Louisiana, U.S.Resting ...

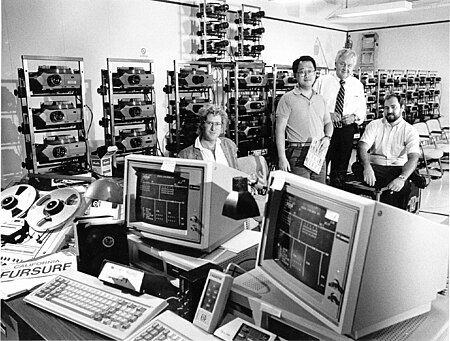

Multi-image is the now largely obsolete practice and business of using 35mm slides (diapositives) projected by single or multiple slide projectors onto one or more screens in synchronization with an audio voice-over or music track. Multi-image productions[1] are also known as multi-image slide presentations, slide shows and diaporamas and are a specific form of multimedia or audio-visual production. Soft-edge masking and overlap for projected panoramas. One of the hallmarks of multi-...

Perangko Pilihan [perbarui] Halo, Bennylin, selamat datang di Wikipedia bahasa Indonesia! Memulai Memulai Para pengguna baru dapat melihat Pengantar terlebih dahulu. Anda bisa mengucapkan selamat datang kepada Wikipediawan lainnya di Halaman perkenalan Bingung mulai menjelajah dari mana? Kunjungi Halaman sembarang Untuk mencoba-coba menyunting, silakan gunakan bak pasir. Baca juga Pancapilar sebelum melanjutkan. Ini adalah lima hal penting yang mendasari hari-hari Anda bersama Wikipedia di s...

Region in Catalonia This article is about the Catalan vegueria. For the comarca, see Gironès. For other uses, see Girona region (disambiguation). The Girona region within Catalonia Comarques Gironines or the Girona region[1] is one of the eight regions (vegueries) defined by the Regional Plan of Catalonia. It has an area of 5,558 km² and 761,690 inhabitants as of 2022.[2] Located in the far east of Catalonia and bordering Pyrénées-Orientales (Occitania, France)...

Standing in the Marowijne River The geology of Suriname is predominantly formed by the Guyana Shield, which spans 90% of its land area. Coastal plains account for the remaining ten percent. Most rocks in Suriname date to the Precambrian. These crystalline basement rocks consists of granitoid and acid volcanic rocks with enclaves of predominantly low-grade metamorphic, geosynclinal rocks in the Marowijne area and of probably considerably older rocks in the Falawatra group of the Bakhuisgebirge...

Европейская сардина Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеГруппа:Костные рыбыКласс:Лучепёрые рыбыПодкласс:Новопёры...

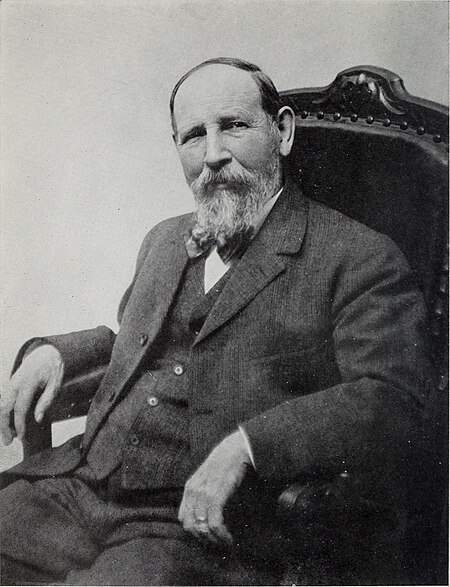

American zoologist and ornithologist Joel Asaph AllenBorn(1838-07-19)July 19, 1838Springfield, MassachusettsDiedAugust 29, 1921(1921-08-29) (aged 83)NationalityAmericanAlma materHarvard UniversityKnown forAllen's ruleParentsJoel Allen (father)Harriet Trumbull (mother)Scientific careerFieldsOrnithologyZoologyInstitutionsAmerican Academy of Arts and SciencesMuseum of Comparative ZoologyAmerican Association for the Advancement of ScienceAudubon SocietyAmerican Philosophical Societ...

Ancient Greek goddess of the day HemeraPersonification of dayRelief of Hemera from the Aphrodisias SebasteionAbodeSky and TartarusPersonal informationParentsErebus and NyxSiblingsAetherConsortAetherEquivalentsRoman equivalentDies Part of a series onAncient Greek religion Origins Ancient Greek religion Mycenaean Greece, Mycenaean religion and Mycenaean deities Minoan Civilization, Minoan religion Classical Greece Hellenistic Greece, Hellenistic religion Sacred PlacesSacred Islands Delos Ithaca...

For other uses, see RTX. Resiniferatoxin Names IUPAC name [(1R,2R,6R,10S,11R,13R,15R,17R)-13-Benzyl-6-hydroxy-4,17-dimethyl-5-oxo-15-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-12,14,18-trioxapentacyclo[11.4.1.01,10.02,6.011,15]octadeca-3,8-dien-8-yl]methyl 2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acetate Identifiers CAS Number 57444-62-9 Y 3D model (JSmol) Interactive image ChEMBL ChEMBL448382 Y ChemSpider 4642871 Y IUPHAR/BPS 2491 MeSH resiniferatoxin PubChem CID 104826 UNII A5O6P1UL4I Y CompTox Dashboard (EP...

Komite Penanganan Corona Virus Disease 2019 dan Pemulihan Ekonomi NasionalInformasi lembagaDibentuk20 Juli 2020 (2020-07-20)Nomenklatur lembaga sebelumnyaGugus Tugas Percepatan Penanganan COVID-19beserta 18 lembaga lainnya yang dibubarkan[1]Dibubarkan05 Agustus 2023 (2023-08-05)Wilayah hukumPemerintah IndonesiaKantor pusatKantor Sekretariat Presiden, Istana Negara, Jakarta, Indonesia6°10′06″S 106°49′28″E / 6.1683°S 106.8244°E / -6.1683; 10...

Harbin Taiping International Airport哈尔滨太平国际机场Hāěrbīn Tàipíng Guójì JīchǎngIATA: HRBICAO: ZYHB HRBLocation in Heilongjiang province InformasiJenisPublicPengelolaCivil GovernmentMelayaniHarbinLokasinear the town of Taiping, Daoli District, HarbinKetinggian dpl139 mdplKoordinat45°37′24.25″N 126°15′01.18″E / 45.6234028°N 126.2503278°E / 45.6234028; 126.2503278Landasan pacu Arah Panjang Permukaan kaki m 05/23 10,500 3,200 Asp...

Organism that eats mostly or exclusively animal tissue This article is about the general concept of a meat-eating animal. For the mammal order, see Carnivora. For other uses, see Carnivore (disambiguation). Carnivorous redirects here. For the Hawkwind album, see Carnivorous (album). Lions are obligate carnivores consuming only animal flesh for their nutritional requirements. A carnivore /ˈkɑːrnɪvɔːr/, or meat-eater (Latin, caro, genitive carnis, meaning meat or flesh and vorare meaning ...

Raised light sources which are powered by solar panels Solar street lighting Solar street lights are raised light sources which are powered by solar panels generally mounted on the lighting structure or integrated into the pole itself. The solar panels charge a rechargeable battery, which powers a fluorescent or LED lamp during the night. Features Most solar lights turn on and turn off automatically by sensing outdoor light using solar panel voltage. Solar streetlights are designed to work th...

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Markham Airport – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Airport in Markham, OntarioToronto/Markham AirportFinal approach into MarkhamIATA: noneICAO: noneTC LID: CNU8SummaryAirport typePrivateOperatorM...

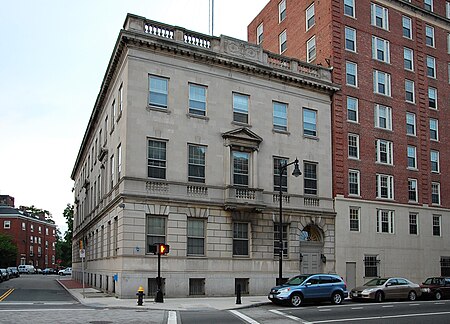

College in Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. This article has an unclear citation style. The references used may be made clearer with a different or consistent style of citation and footnoting. (October 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) A former Grahm building, now the Myles Annex owned by Boston University Grahm Junior College was a non-profit junior college located in Boston, Massachusetts. It opened in 1951 under the name Cambridge School, as part of a chain of schools that start...

Dutch-born Austrian diplomat, librarian, and government official Gottfried Freiherr van SwietenBornGodefridus Bernardus Godfried van Swieten(1733-10-29)October 29, 1733Leiden, South Holland, Republic of the Seven United NetherlandsDiedMarch 29, 1803(1803-03-29) (aged 69)Vienna, Habsburg EmpireEducationTheresianum, a Jesuit school in ViennaOccupation(s)diplomat, librarian, officialFatherGerard van Swieten Gottfried Freiherr van Swieten (29 October 1733 – 29 March 1803)[1] was a ...