South African steam locomotive tenders

|

Read other articles:

Banu Hashim (Arab: بنو هاشمcode: ar is deprecated )Bani Quraisy dari Bani IsmailNisbahal-HasyimiLokasi asal leluhurArabia (mayoritas) Timur Tengah Afrika Utara Diturunkan dariHasyim bin Abdul ManafSuku indukBani QuraisyCabangSayyid Bani AbbasAgamaPaganisme, lalu Islam Bagian dari seri tentangMuhammad Kehidupan dan karierKehidupan di Mekkah • Hijrah • Muhammad di Madinah • Haji Wada' • Pernikahan • Wafat Karier Wahyu pertama Karier militer Karier diplomatik Pembebasan Mekkah H...

Duang Jai Nai MontraNama alternatifHeart of the MontraThe Curse of LoveJudul asliดวงใจในมนตรา GenreRomansaDramaSupernaturalPemeranPhakin KhamwilaisakNuttanicha DungwattanawanichPeter Corp DyrendalKannarun WongkajornklaiLagu pembukaถ้าไร้เธอ oleh Phakin KhamwilaisakLagu penutupสุดท้าย oleh Lydia Sarunrat DeaneNegara asalThailandBahasa asliThaiJmlh. episode16ProduksiProduserArunocha BhanubandhuDurasi81 menitRumah produksiBroadcast Thai Te...

Video streaming site DailymotionLogo used since 2023Type of businessSubsidiaryType of siteOnline video platformAvailable in149 countries and 183 languagesFounded15 March 2005; 19 years ago (2005-03-15)Headquarters140 Boulevard Malesherbes - 75017 Paris, FranceCountry of originFranceArea servedWorldwideFounder(s)Benjamin BejbaumOlivier PoitreyChairmanMaxime SaadaCEOMaxime SaadaKey peopleBenjamin Bejbaum (co-founder)Employees450[1]ParentVivendiURLdailymo...

Ryan Sessegnon Sessegnon bermain untuk Fulhampada tahun 2017Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Kouassi Ryan Sessegnon[1]Tanggal lahir 18 Mei 2000 (umur 23)[2]Tempat lahir Roehampton, London, InggrisTinggi 5 ft 10 in (1,78 m)[3]Posisi bermain Sayap Kiri / Bek KiriInformasi klubKlub saat ini Tottenham HotspurNomor 19Karier junior2008–2016 FulhamKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2016–2019 Fulham 110 (23)2019– Tottenham Hotspur 38 (2)2020–2021 →...

1937 film by Spencer Gordon Bennet Law of the RangerTheatrical release posterDirected bySpencer Gordon BennetScreenplay byNate GatzertStory byJesse DuffyJoseph LeveringProduced byLarry DarmourStarringRobert AllenElaine ShepardJohn MertonWally WalesLafe McKeeTom LondonCinematographyJames S. Brown Jr.Edited byDwight CaldwellProductioncompanyLarry Darmour ProductionsDistributed byColumbia PicturesRelease date May 11, 1937 (1937-05-11) Running time58 minutesCountryUnited StatesLang...

Upper Peninsula miners' strikeSailors from Michigan, seen here at an unknown date, helped put down the 1865 miner's strike.DateJuly 1865LocationMarquette, MichiganGoalsHigher wagesMethodsStrikes, lootingvteMetal mining strikes 1800s Upper Peninsula 1865 Coeur d'Alene 1892 Cripple Creek 1894 Leadville 1896–97 Coeur d'Alene 1899 1900s–1920s Colorado Labor Wars (Idaho Springs) 1903–04 Cananea 1906 Goldfield 1906–07 Copper Country 1913–14 Bisbee 1917 Anaconda Road 1920 1930s–1970s Emp...

The native form of this personal name is Mathai Varghese. This article uses Western name order when mentioning individuals. Varghese MathaiBornIndiaAlma materIllinois Institute of Technology B.A. (1981)Massachusetts Institute of Technology Ph.D. (1986)Known forMathai-Quillen formalismT-duality in a background fluxFractional and Projective Index theoryAwardsAustralian Mathematical Society Medal[1] (2000) Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science.[2] (2011) ARC ...

Small ironclad warship with large guns This article is about the type of warship. For the U.S. Navy warship which gave its name to this type, see USS Monitor. USS Monitor, the first monitor (1861) HMS Marshal Ney used a surplus 15-inch gun battleship turret. A monitor is a relatively small warship that is neither fast nor strongly armored but carries disproportionately large guns. They were used by some navies from the 1860s, during the First World War and with limited use in the Se...

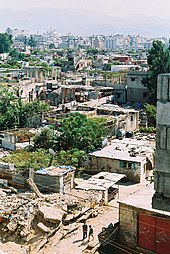

Palestinian settlement in Beirut, Lebanon Shatila in 2019 Shatila in 2003 The Shatila refugee camp (Arabic: مخيم شاتيلا), also known as the Chatila refugee camp, is a settlement originally set up for Palestinian refugees in 1949. It is located in southern Beirut, Lebanon and houses more than 9,842 registered Palestine refugees.[1] Since the eruption of the Syrian Civil War, the refugee camp has received a large number of Syrian refugees. In 2014, the camp's population was es...

この記事は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。(このテンプレートの使い方)出典検索?: コルク – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii · J-STAGE · NDL · dlib.jp · ジャパンサーチ · TWL(2017年4月) コルクを打ち抜いて作った瓶の栓 コルク(木栓、�...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Jury (homonymie). Cet article est une ébauche concernant le droit. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Consultez la liste des tâches à accomplir en page de discussion. The Jury de John Morgan (1861) : jury criminel à Aylesbury, au Royaume-Uni. Un jury est un ensemble de citoyens, appelés des jurés, chargés de rendre un verdict dans un procès. Dans son se...

Peak District SituaciónPaís Reino UnidoDivisión DerbyshireCoordenadas 53°21′00″N 1°50′00″O / 53.35, -1.8333333333333Datos generalesFecha de creación 1951Superficie 1444 kilómetros cuadrados Peak District Ubicación en Reino Unido.Sitio web oficial[editar datos en Wikidata] El Peak District es una zona de montaña en Inglaterra, en el extremo sur de los Peninos. Se encuentra principalmente en el norte de Derbyshire, pero también incluye parte...

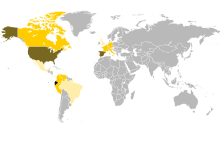

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Ecuadorians – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Citizens of Ecuador Ethnic group Ecuadorians EcuatorianosFlag of Ecuador; symbol of Ecuadorian unityTotal populationc. 18.5 million(Diaspor...

French judoka (born 1966) Stéphane TraineauPersonal informationFull nameStéphane André Michel TraineauBorn (1966-09-16) 16 September 1966 (age 57)OccupationJudokaSportCountryFranceSportJudoWeight class–95 kg, –100 kgAchievements and titlesOlympic Games (1996, 2000)World Champ. (1991)European Champ. (1990, 1992, 1993,( 1999) Medal record Men's judo Representing France Olympic Games 1996 Atlanta –95 kg 2000 Sydney –10...

Music genre combining jazz methods with rock music, funk, and rhythm and blues Parts of this article (those related to History) need to be updated. The reason given is: History section does not cover any other decade besides the 70s and is completely out of touch with recent developments. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (November 2023) Jazz fusionTrumpet player Miles Davis was a key figure in the development of fusionStylistic originsJa...

For grammatical articles in English, see English articles. Word used with a noun to indicate the type of reference being made by the noun In grammar, an article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech. In English, both the and a(n) are articles, which combine with nouns to form noun phrases. Articles typically specify the grammatical defin...

Alberto VII de Mecklemburgo Información personalNombre en alemán Albrecht VII. von Mecklenburg Nacimiento 25 de julio de 1486jul. Wismar (Ducado de Mecklemburgo-Schwerin) Fallecimiento 7 de enero de 1547jul. (60 años)Schwerin (Alemania) Sepultura Abadía de Doberan FamiliaFamilia Casa de Mecklemburgo Padres Magnus II de Mecklenburgo Sofía de Pomerania Cónyuge Ana de Brandeburgo (desde 1524juliano, desde 1524, hasta 1547juliano) Hijos Ulrico III de Mecklemburgo-GüstrowJuan Alberto I...

Questa voce sull'argomento Kosovo è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Mappa del Kosovo Il Kosovo è situato nella parte sud-occidentale della Penisola Balcanica. Il suo piccolo territorio è prevalentemente montuoso ed è senza sbocco al mare. Il paese è situato fra i 41°30' e i 43°30' di latitudine nord e tra i 20° e i 22° di longitudine est. Il punto più meridionale del paese è a 41° 52' 30 di latitudine nord, un picco che condiv...

SEG Racing 2015GénéralitésÉquipe SEG Racing AcademyCode UCI SEGStatut Équipe continentalePays Pays-BasSport Cyclisme sur route, sport cyclisteEffectif 16Manager général Eelco Berkhout (d)PalmarèsNombre de victoires 7-SEG Racing Academy 2016modifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata La saison 2015 de l'équipe cycliste SEG Racing est la première de cette équipe. Préparation de la saison 2015 Sponsors et financement de l'équipe Cette section est vide, insuffisamment déta...

Río Misisipi(Mississippi River) El río Misisipi en su confluencia con el río Misuri, al sur de San Luis (Misuri)Ubicación geográficaCuenca Río MisisipiNacimiento Lago Itasca (Minesota)Desembocadura Golfo de MéxicoCoordenadas 47°14′23″N 95°12′27″O / 47.2397, -95.2075Ubicación administrativaPaís Estados UnidosDivisión Minnesota Wisconsin Iowa Misuri Illinois Kentucky Tennessee Arkansas Misisipi ...