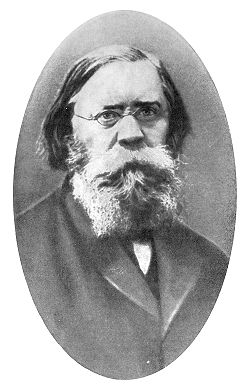

Pyotr Lavrov

Pyotr Lavrovich Lavrov[a] (14 June [O.S. 2 June] 1823 – 6 February [O.S. 25 January] 1900) was a prominent Russian theorist of narodism, philosopher, publicist, revolutionary, sociologist, and historian. BiographyLavrov was born into a military family of hereditary nobles.[1][2] His father was a retired artillery officer of the Imperial Russian Army and his mother was from a Russified Swedish merchant family.[3] He entered a military academy and graduated in 1842 as an army officer. He became well-versed in natural science, history, logic, philosophy, and psychology. He also taught mathematics for two decades, being a professor at the Artillery College in St. Petersberg.[4]  Lavrov joined the revolutionary movement as a radical in 1862. He was arrested following Karakozov's failed attempt to assassinate Alexander II. Letters and poems which were considered compromising had been found at his house and he was imprisoned in the military prison at St. Petersberg for nine months. No charge of being involved in the conspiracy was laid against him, but he was found guilty of having published subversive ideas and having shown sympathy with men of criminal tendencies.[4] He was sentenced to exile in Vologda; after three years escaped and fled abroad, via a short stay in St. Petersberg to acquire a fake passport.[4] In France, he lived mostly in Paris, where he became a member of the Anthropological Society. Lavrov had been attracted to European socialist ideas early on, though at first he did not know how they applied to Russia.[5] While in Paris, Lavrov fully committed himself to the revolutionary socialist movement. He became a member of the Ternes section of the International Workingmen's Association in 1870. He was also present at the start of the 1871 Paris Commune, and soon went abroad to generate international support. Lavrov arrived in Zürich in November 1872, and became a rival of Mikhail Bakunin in the "Russian Colony". In Zürich he lived in the Frauenfeld house near the university. Lavrov tended more toward reform than revolution, or at least he saw reform as salutary. He preached against the conspiratorial ideology of Peter Tkachev and others like him. Lavrov believed that while a coup d'état would be easy in Russia, the creation of a socialist society needed to involve the Russian masses.[5] He founded the journal Вперед! (lit. Forward!)in 1872, its first issue appearing in August 1873. Lavrov used this journal to publicize his analysis of Russia's special historical development. He spent time in London in 1877 and 1882.  Lavrov wrote prolifically for more than 40 years. His works include The Hegelian Philosophy (1858–59) and Studies in the Problems of Practical Philosophy (1860). While living in exile, he edited his Socialist review, Веперед! A contribution to the revolutionary cause, Historical Letters (1870), was written under the pseudonym "Mirtov". The letters greatly influenced revolutionary activity in Russia. He was called "Peter Lawroff" in Die Neue Zeit (1899–1900) by K. Tarassoff. Revolutionary ideology In Peter Lavrov's view, socialism was the natural outcome of Western European historical development. He believed that the bourgeois mode of production planted the seeds of its own destruction. "Lavrov began his revolutionary career with the assumption that the future belonged to West European scientific socialism, as created by material conditions of West European civilization."[5] Lavrov recognized that Russia's historical development was significantly different from that of Western Europe, though he still maintained hope that Russia might join in the greater European socialist movement. In Lavrov's analysis of Russia's historical development, he concluded that the essence of Russia's peculiarity rested on the fact that they had not experienced feudalism and all of its progressive features. Russia had been isolated from European development by the Mongol conquest in the thirteenth century. In 1870, Lavrov published a comparison of the levels of economic, political and social development of several Western European nations and Russia, noting the relatively backward and poor condition of Russia.[5] Despite Lavrov's historical analysis, he still believed a socialist revolution was possible in Russia. One of his contemporaries, Georgi Plekhanov, believed that a socialist revolution would only come with the development of a revolutionary workers’ party. In other words, he believed that Russia would have to wait for the same historical development experienced by the West. Lavrov rejected this outlook, believing it possible to create socialism by basing revolutionary tactics on Russia's individual history. Almost 90 percent of Russia's population were peasants, and there was also the intelligentsia: a unique bunch of people without any class affiliations, who, "unlike other elements of Russian society, were unflawed by the past."[5] Thus, Lavrov felt that a true socialist revolution would have to integrate the rural population in order to succeed. Lavrov considered the intelligentsia the only portion of society capable of preparing Russia for participation in a worldwide socialist revolution. He gave them the task of compensating for the shortfalls of Russian historical development by organizing the people, teaching them scientific socialism, and finally, preparing to take up arms with the people when the time would come.[5] Lavrov on Social SolidarityIn his “Historical Letters” Lavrov accentuated the indissoluble connection between sociology as a science and basic principles of individual morality. According to him, sociological knowledge always depends upon scholars’ consciously chosen ideals. The majority of researchers stress the heterogeneity of Lavrov's ideas as well as the fact that a considerable impact was made upon him both by the leaders of the positivist tradition and by Karl Marx.[6] All those impacts were in some way synthesized in Lavrov's idea of solidarity as the key issue of sociological research. Lavrov defined sociology as a science dealing with forms of social solidarity, which he subdivided into three major types: - unconscious solidarity of custom; - purely emotional solidarity, based on impulses not controlled by critical reflection; - “conscious historical solidarity” resulting from a common effort to attain a consciously selected and rationally justified goal. The latter represented the highest and the most significant type of human solidarity. It developed later than the first two types and proclaimed the conversion of the static “culture” into the dynamic “civilization.” To sum it up, social solidarity in Lavrov's view is “the consciousness that personal interest coincides with social interest, that personal dignity is maintained only by upholding the dignity of all who share in this solidarity”.[7] Otherwise it is a mere community of habits, interests, affects, or convictions. Thus solidarity is an essential premise of the existence of society. Solidary interaction distinguishes society from a simple gathering of individuals, the latter phenomenon constituting no sociological object. Moreover, the condition of individuals being conscious creatures excludes from the field of sociology forms of solidarity / solidary interaction performed by unconscious organisms, or, in other words, marks the borderline between social and biological phenomena. Further reading

NotesReferencesWikimedia Commons has media related to Pyotr Lavrov.

|

||||||||||||||||||