Pratt & Whitney J57

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Kue Apem Apam atau apem (dikenal juga dengan appam di negeri asalnya India[1]) adalah makanan yang terbuat dari tepung beras yang didiamkan semalam dengan mencampurkan telur, santan, gula dan tape serta sedikit garam kemudian dibakar atau dikukus. Bentuknya mirip serabi, tetapi lebih tebal.[2] Sejarah dan tradisi Kue apam barabai, salah satu jenis apam yang populer di Kalimantan Selatan Kue Apam Manis India, slah satu jenis apam yang populer di India Selatan, Sri Langka, Malay...

Синелобый амазон Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:ЗавропсидыКласс:Пт�...

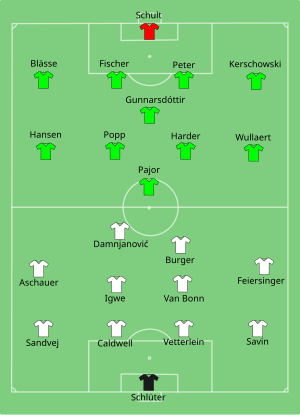

Football tournament season 2016–17 DFB-Pokal FrauenTournament detailsCountryGermanyTeams56Final positionsChampionsVfL WolfsburgRunner-upSC SandTournament statisticsMatches played55Goals scored249 (4.53 per match)Top goal scorer(s)Nina BurgerAnnabel Jäger(5 goals)← 2015–162017–18 → The DFB-Pokal 2016–17 was the 37th season of the cup competition, Germany's second-most important competition in women's football. Results First round The draw was held ...

Norwegian architect (1907–1980) Olav Tveten (5 April 1907 – 19 December 1980) was a Norwegian architect.[1] Aerial view of Jordal Idrettspark in 1965 Tveten was born in Bærum in Akershus, Norway. He was the son of Magnus Tveten (1867-1950) and Mathilde Kristine Kirkeby (1867-1944). He finished his education at the Norwegian Institute of Technology in 1932. He was employed as an architectural assistant in Tønsberg in 1933 and with architect Ragnvald Tønsager (1888-1964) in Oslo ...

Artikel atau sebagian dari artikel ini mungkin diterjemahkan dari Special Period di en.wikipedia.org. Isinya masih belum akurat, karena bagian yang diterjemahkan masih perlu diperhalus dan disempurnakan. Jika Anda menguasai bahasa aslinya, harap pertimbangkan untuk menelusuri referensinya dan menyempurnakan terjemahan ini. Anda juga dapat ikut bergotong royong pada ProyekWiki Perbaikan Terjemahan. (Pesan ini dapat dihapus jika terjemahan dirasa sudah cukup tepat. Lihat pula: panduan penerjema...

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Трал. Трал — высокопроизводительное буксируемое (тралирующее) сетное отцеживающее орудие лова, широко применяемое в мировом морском промышленном рыболовстве. Представляет собой большой сетный буксируемый рыболовным...

MV Cape Pine A SC-497-class submarine chaser of the same type as USS SC-715 History United States NameUSS SC-715 BuilderFisher Boat Works, Detroit, Michigan Laid down14 May 1942 Launched23 October 1942 Commissioned4 December 1942 Out of serviceTransferred to US Coastguard on 9 January 1946 United States NameUSCGC Air Killdeer (WAVR 433) In service9 January 1946 Out of serviceSold into mercantile service on 19 January 1948 RenamedCape Pine on 14 May 1951 Identification IMO number: 506175...

Ne doit pas être confondu avec Jimmy Dean ou James Deen. Pour les articles homonymes, voir James Dean (homonymie) et Dean. James Dean James Dean dans le film La Fureur de vivre de 1955. Données clés Nom de naissance James Byron Dean Surnom Jimmy Dean Naissance 8 février 1931Marion, Indiana (États-Unis) Nationalité Américaine Décès 30 septembre 1955 (à 24 ans)Cholame, Californie (États-Unis) Profession Acteur Films notables À l'est d'Eden (1955)La Fureur de vivre (1955)...

1960s British rock supergroup For other uses, see Cream (disambiguation). CreamCream in 1967. L–R: Ginger Baker, Jack Bruce and Eric Clapton.Background informationOriginLondon, EnglandGenres Psychedelic rock[1] blues rock[2] acid rock[3] hard rock[4] jam band[5] Years active 1966 (1966)–1968 1993 2005 Labels Reaction Polydor Atco RSO Reprise Past members Jack Bruce Eric Clapton Ginger Baker Cream were a British rock band formed in London in 196...

Marla MaplesMaples tahun 2007LahirMarla Ann Maples[1]27 Oktober 1963 (umur 60)Dalton, Georgia, Amerika SerikatNama lainMarla TrumpPekerjaanAktris, tokoh televisiTahun aktif1990-an-sekarangPartai politikRepublikSuami/istriDonald Trump (m. 1993; c. 1999)AnakTiffany Trump Marla Ann Maples (lahir 27 Oktober 1963) adalah aktris dan tokoh televisi Amerika Serikat. Ia dikenal atas skandal perselingkuhannya dan pernikahannya ...

Monkey Boys ProductionsIndustryTheater, TV, Film - Puppet, Prop, Costume, Creature, and Practical Effect Design and Fabrication; Puppetry; ProductionFounded2006FounderMarc Petrosino, Michael Latini, Russell Tucker, and Scott HitzHeadquartersUnited StatesMembersMarc Petrosino and Michael LatiniWebsitemonkeyboysproductions.com Monkey Boys Productions is a two time Emmy nominated production company that creates puppets, props, creatures, costumes, practical effects and original content for film,...

Jeisson Vargas Nazionalità Cile Altezza 160 cm Peso 60 kg Calcio Ruolo Attaccante Squadra Universidad de Chile CarrieraSquadre di club1 2014-2016 Universidad Católica23 (6)2016 Montréal Impact0 (0)2017→ Estudiantes9 (0)2017→ Universidad Católica11 (1)2018-2019 Montréal Impact19 (4)2019→ Universidad Católica3 (0)2020-2021 Unión La Calera54 (13)2022- Universidad de Chile23 (7)Nazionale 2016-2017 Cile U-208 (3) 1 I due numeri in...

Honda Automobiles logo Honda has produced the following cars, SUVs, and light trucks. Current models Model Calendar yearintroduced Current model Main markets Vehicle description Introduction Update (facelift) Hatchback Brio 2011 2018 2023 Southeast Asia Entry-level hatchback, currently only produced in Indonesia for several Southeast Asian markets. City 19812020 (reintroduction) 2020 – Southeast Asia and South America[1] Hatchback version of the City subcompact car. The newest mode...

Suburb of Port Stephens Council, New South Wales, AustraliaHeatherbraeNew South WalesClayton Road roundabout, 2023HeatherbraeCoordinates32°46′54″S 151°44′04″E / 32.78167°S 151.73444°E / -32.78167; 151.73444Population512 (2016 census)[2] • Density38.7/km2 (100/sq mi) [Note 1]Postcode(s)2324Elevation10 m (33 ft)[Note 2]Area12.7 km2 (4.9 sq mi)[Note 3]Time zoneAEST (UTC+10) �...

Stasiun Higashi-Rokusen (東六線駅 Higashi-Rokusen-eki) adalah sebuah stasiun kereta api yang berada di Jalur Utama Sōya terletak di Higashimachi, Kenbuchi, Subprefektur Kamikawa, Hokkaido, Jepang, yang dioperasikan oleh JR Hokkaido. Stasiun ini diberi nomor W39. Stasiun Higashi-Rokusen東六線駅Bangunan Stasiun Higashi-RokusenLokasiHigashimachi, Kenbuchi, Kamikawa District, Hokkaido 098-0338, JepangJepangKoordinat44°4′7″N 142°23′18″E / 44.06861°N 142.38833°E...

هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالات أخرى قليلة جدًا. فضلًا، ساعد بإضافة وصلة إليها في مقالات متعلقة بها. (مارس 2024) خدمة الغيوم (بالإنجليزية The Service of Clouds) - هي رواية للكاتبة الإنجليزية سوزان هيل، نشرت لأول مرة في عام 1998 من قبل تشاتو وويندوس. تأخذ خدمة الغيوم The Service of Clouds معلوم�...

This article is about the hospital in Sri Lanka. For the former hospital in England, see Western Hospital, Fulham. For the hospital in Canada, see Toronto Western Hospital. Hospital in Colombo, Sri LankaWestern HospitalWestern Hospital logoGeographyLocationColombo, Sri LankaCoordinates06°54′42″N 79°53′8″E / 6.91167°N 79.88556°E / 6.91167; 79.88556OrganisationCare systemPrivateFundingFor-profit hospitalTypeGeneralServicesBeds25HistoryOpened1984LinksWebsitewe...

大日本帝国內閣高橋內閣たかはしないかく第20任內閣總理大臣高橋是清肖像內閣總理大臣高橋是清(第20任)成立日期1921年(大正10年)11月13日總辭日期1922年6月12日執政黨/派系立憲政友會內閣閣僚名簿(首相官邸) 高橋內閣(日语:高橋內閣/たかはしないかく Takahashi Naikaku */?)是日本子爵、貴族院議員高橋是清就任第20任內閣總理大臣(首相)後,自1921�...

The Wharf Theatre adalah sebuah teater di Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Teater ini adalah bagian dari Sydney Theatre Company dan terletak di Pier 4/5 bekas fasilitas pelabuhan Sydney di Walsh Bay di Dawes Point. Sejarah Tahun 1831, dermaga pertama di daerah Pier 4/5 dibangun dan dinamai 'Pitman's Wharf'. Tahun 1919, pembangunan Pier 4/5 diselesaikan oleh H.D Walsh. Tahun 1979, Sydney Theatre Company mencari sebuah tempat untuk kantornya. Elizabeth Butcher, Administrator NIDA, menemukan...

Yao BeinaLahir(1981-09-26)26 September 1981Wuhan, Hubei, TiongkokMeninggal16 Januari 2015(2015-01-16) (umur 33)Shenzhen, Guangdong, TiongkokAlmamaterKonservatorium Musik TiongkokPekerjaanPenyanyiTahun aktif2005-2015[1]Orang tuaYao FengLi Xinmin Yao Beina Hanzi tradisional: 姚貝娜 Hanzi sederhana: 姚贝娜 Alih aksara Mandarin - Hanyu Pinyin: Yáo Bèinà Karier musikGenreMandapop, Lagu daerah, Rock, R&B, JazzInstrumenPianoLabelYuechao Yinshang (2010-2012) Huayi Brot...