Minimum support price (India)

|

Read other articles:

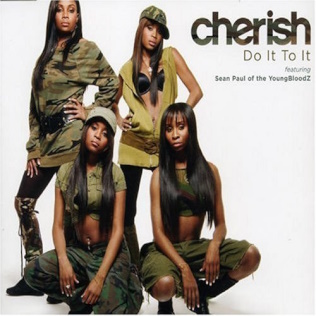

2006 single by Cherish Do It to ItSingle by Cherish featuring Sean Paul of the YoungBloodZfrom the album Unappreciated B-sideGhetto MentalityHe Said She SaidReleasedMarch 21, 2006 (2006-03-21)GenreCrunk&BLength3:47LabelSho'nuffCapitolSongwriter(s)Sean Paul JosephFarrah KingNeosha KingFelisha King HarveyFallon KingRodney RichardJohn WilliamsProducer(s)Don VitoCherish singles chronology Miss P. (2003) Do It to It (2006) Unappreciated (2006) Alternative coverDigital releas...

Biografi ini tidak memiliki sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak dapat dipastikan. Bantu memperbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan sumber tepercaya. Materi kontroversial atau trivial yang sumbernya tidak memadai atau tidak bisa dipercaya harus segera dihapus.Cari sumber: Acep Adang Ruhiat – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR (Pelajari cara dan kapan saatnya untuk menghapus pesan templat ini) Acep Adang Ruhiat Anggota Dewan Perwakilan ...

Keuskupan Agung Foggia-BovinoArchidioecesis Fodiana-BovinensisKatolik Katedral FoggiaLokasiNegara ItaliaProvinsi gerejawiFoggia-BovinoStatistikLuas1.666 km2 (643 sq mi)Populasi- Total- Katolik(per 2006)218.300217,100 (99.5%)Paroki55InformasiDenominasiGereja KatolikRitusRitus RomaPendirian25 Juni 1855 (168 tahun lalu)KatedralCattedrale di S. Maria Assunta in Cielo (Iconavetere), FoggiaKonkatedralBasilica Concattedrale di S. Maria Assunta, BovinoKepemimpi...

The IslandLogo Sunday Island (edisi Minggu The Island)TipeSurat kabar harianFormatPrint, onlinePemilikUpali NewspapersDidirikan1981 (1981)BahasaInggrisPusat223, Bloemendhal Road, Colombo 13, Sri LankaSirkulasi surat kabar70,000 (Daily Island)103,000 (Sunday Island)Surat kabar saudariDivainaSitus webisland.lk The Island adalah sebuah surat kabar berbahasa Inggris harian di Sri Lanka. Surat kabar tersebut diterbitkan oleh Upali Newspapers. Sebagai surat kabar bersaudari dari Divaina, The I...

DominoFilm posterSutradaraTony ScottProduserSamuel HadidaTony ScottDitulis olehRichard KellyPemeranKeira KnightleyMickey RourkeEdgar RamirezLucy LiuJacqueline BissetDelroy LindoNaratorKeira KnightleyPenata musikHarry Gregson-WilliamsSinematograferDan MindelPenyuntingWilliam GoldenbergChristian WagnerDistributorNew Line Cinema (AS)Paramount Pictures (non AS)Tanggal rilis14 Oktober 2005Durasi127 menitNegaraAmerika SerikatPrancisBritania RayaBahasaInggrisAnggaran$50,000,000Pendapatankotor$...

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. (December 2023) Census-designated place in Virginia, United StatesReston, VirginiaCensus-designated placeReston Town CenterLocation of Reston in Fairfax County, VirginiaReston, VirginiaShow map of Northern VirginiaReston, VirginiaShow map of VirginiaReston, VirginiaShow map of the United StatesCoordin...

AFMNama resmiAlex von Falkenhausen MotorenbauKantor pusatMünchen, JermanPendiriAlexander von FalkenhausenPembalap terkenalHans StuckSejarah dalam ajang Formula SatuMesinBMW, Bristol, KüchenGelar Konstruktor0Gelar Pembalap0Jumlah lomba4Menang0Posisi pole0Putaran tercepat0Lomba pertamaGrand Prix Swiss 1952Lomba terakhirGrand Prix Italia 1953 Alex von Falkenhausen Motorenbau (AFM) (beberapa menyebutkan huruf M singkatan untuk München) adalah konstruktor balap mobil dari Jerman. Tim ini didiri...

Holiday on 29 November Map of Albania during World War II Liberation Day (Albanian: Dita e Çlirimit) in Albania is commemorated as the day, November 29, 1944, in which the country was liberated from Nazi Germany forces by the Albanian resistance during World War II.[1] Background German soldiers in Albania After Italy was defeated by the Allies, Germany occupied Albania in September 1943, dropping paratroopers into Tirana before the Albanian guerrillas could take the capital, and the...

Sky 2014GénéralitésÉquipe Ineos GrenadiersCode UCI SKYStatut UCI ProTeamPays Royaume-UniSport Cyclisme sur routeEffectif 29Manager général Dave BrailsfordPalmarèsNombre de victoires 25Meilleur coureur UCI Christopher Froome (7e)Classement UCI 9e (UCI World Tour)Sky 2013Sky 2015modifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata Le bus principal lors de la 3e étape du Tour de France 2014 au Touquet-Paris-Plage. Une des voitures lors de la 3e étape du Tour de France 2014 au...

Salah satu sudut Fort Lauderdale, menampilkan River House Fort Lauderdale (terkenal sebagai Venesia dari Amerika) ialah sebuah kota di Amerika Serikat yang terletak di negara bagian Florida. Pada 2000 kota ini berpenduduk 152.397. Kota ini ialah ibu kota Broward County. Pendidikan Sunland Park Elementary School dan Arthur Ashe Middle School[1] mendapat nilai gagal pada Tes Penilaian Komprehensif Florida (FCAT) tahun 2007, sementara 10 (dari 16) sekolah dasar dan satu (dari empat) seko...

1528 paintings by Lucas Cranach the Elder Adam and EveArtistLucas Cranach the ElderYear1528MediumOil on panelDimensions172 cm × 124 cm (68 in × 49 in)LocationUffizi, Florence Adam and Eve is a pair of paintings by German Renaissance master Lucas Cranach the Elder, dating from 1528,[1] housed in the Uffizi, Florence, Italy. There are other paintings by the same artist with the same title, depicting the subjects either together in a double por...

Internet country code top-level domain for Macao .moIntroduced17 September 1992TLD typeCountry code top-level domainStatusActiveRegistryMacao Network Information CentreSponsorGovernment of MacauIntended useEntities connected with Portuguese Macau (1992–1999) Macau SAR, China (1999–present) Actual useGets limited use in MacauRegistration restrictionsLimited to local businesses and organizations in MacauStructureSecond-level registrations are now available to registrants who already have th...

This film-related list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. (August 2008) Cinema of Greece List of Greek films Pre 1940 1940s 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s 2010s 2020svte A list of notable films produced in Greece in the 1970s. 1970s Title Director Cast Genre Notes 1970 Reconstitution(Αναπαράσταση) Theo Angelopoulos Toula Stathopoulou, Yannis Totzikas Crime drama 4 Awards in Thessaloniki Film FestivalSelected as one of the 10 best Greek films by Greek Film C...

ShetabOperating areaIranMembers27 (Iranian Banks)ATMs57,000 (2019)Founded2002; 22 years ago (2002)Websitehttps://www.cbi.ir/page/15728.aspxShetab (Persian: شتاب, lit. 'Acceleration'), officially the Interbank Information Transfer Network (Persian: شبکه تبادل اطلاعات بین بانکی), is an electronic banking clearance and automated payments system used in Iran. The system was introduced in 2002 with the intention of creating a uniform back...

Mark MancinaNama lahirMark Alan MancinaGenreSkor film, rock, pop, progressive rockPekerjaanKomposer, produser, aransemen, pemusikInstrumenGitar, pianoTahun aktif1987–sekarangArtis terkaitTrevor Rabin, Hans Zimmer, Phil CollinsSitus webmancinamusic.com Mark Alan Mancina adalah seorang komposer, musisi, aransemen, dan produser berkebangsaan Amerika Serikat. Seorang veteran dari Media Ventures milik Hans Zimmer, ia telah mencetak lebih dari enam puluh film dan serial televisi termasuk Speed, B...

Award given for an accomplishment in the field of music A music award is an award or prize given to honour skill or distinction in music. There are different awards in different countries, and awards may focus on or exclude certain music; for example, some awards are only for classical music and not focused on popular music. Some awards are academic, while others are commercial and created by the music industry. This is a dynamic list and may never be able to satisfy particular standards for ...

Heather MoyseHeather Moyse in una pubblicità istituzionale nel 2011Nazionalità Canada Altezza179 cm Peso72 kg Bob SpecialitàBob a due RuoloFrenatrice Termine carriera2018 Palmarès Competizione Ori Argenti Bronzi Olimpiadi 2 0 0 Mondiali 0 0 2 Vedi maggiori dettagliRugby a 15 RuoloTre quarti ala Termine carriera2010 CarrieraNazionale 2004-10 Canada17 (70) Palmarès Coppa del Mondo ArgentoMosca 2013Rugby a 7 Statistiche aggiornate al 10 ottobre 2018 Modifica dati su Wikidata&...

Эндоцито́з — процесс захвата внешнего материала клеткой, осуществляемый путём образования мембранных везикул. В результате эндоцитоза клетка получает для своей жизнедеятельности гидрофильный материал, который иначе не проникает через липидный бислой клеточной ме...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant le jeu vidéo. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) (voir l’aide à la rédaction). Hanimex TVG 070CGénération DeuxièmeDate de sortie 1976[1]Fin de production ?Média Cartouche[2]modifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata La Hanimex TVG 070C est une console de jeux vidéo de deuxième génération. Elle est sortie en 1976[1]. Notes et références ↑ a et b (de) « Pong konsolen », sur retro-m...

方濟各教宗牧徽細節使用者方濟各啟用2013年格言銘飾Miserando atque eligendo(因仁愛而被揀選) 方濟各教宗牧徽於2013年3月18日公布。方濟各決定保持在1991年晉牧為主教時所用的牧徽與格言,但進行調整以反映教宗的地位[1]。 圖案與盾徽 該教宗牧徽的盾徽上有3個圖案。由於方濟各身為耶穌會成員,最上方為耶穌會的會徽[1]。這個會徽包含了放射狀的太陽,包含了�...