Mantou

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Prof. Dr. Ibrahim bin Ali Al-Ubaid Rektor Universitas Islam MadinahPelaksana TugasMasa jabatan29 Januari 2015 – 31 Oktober 2016 PendahuluProf. Dr. Abdurrahman bin Abdullah as-SanadPenggantiDr.Hatim bin Hasan bin Hamzah al-MarzuqiWakil Rektor Bagian Pengajaran Universitas Islam MadinahPetahanaMulai menjabat 11 Februari 2012Wakil Rektor Bagian Pengembangan Universitas Islam MadinahMasa jabatan30 Juni 2004 – 11 Februari 2012 PenggantiProf. Dr. Mahmud bin Abdurrahman Muh...

Microsoft 365 Tipelayanan daring dan SaaS Versi pertama28 Juni 2011; 12 tahun lalu (2011-06-28) (sebagai Office 365) 10 Juli 2017; 6 tahun lalu (2017-07-10) (sebagai Microsoft 365)GenrePaket aplikasi perkantoran dan Komputasi Awan, SaaS (Langganan perangkat lunak berbentuk layanan)LisensiTrialware (Ritel, lisensi volume, SaaS)Model bisnissubscription business model (en) Bagian dariMicrosoft Office Karakteristik teknisSistem operasiWindows, macOS, Android, iOSFormatunduhan digital In...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant les Jeux olympiques et les sports d'hiver. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Sélection de la ville hôte pour les Jeux olympiques et paralympiques d'hiver de 2018 Logo de la candidature de PyeongChang aux Jeux olympiques de 2018 Détails Comité CIO Session du CIO (ville) 123e ( Durban) Villes candidates Vainqueur (votes) PyeongChang (63 votes) Finaliste (vo...

Calincing tanah Oxalis barrelieri TaksonomiDivisiTracheophytaSubdivisiSpermatophytesKladAngiospermaeKladmesangiospermsKladeudicotsKladcore eudicotsKladSuperrosidaeKladrosidsKladfabidsOrdoOxalidalesFamiliOxalidaceaeGenusOxalisSpesiesOxalis barrelieri Linnaeus, 1762 lbs Calincing tanah adalah salah satu tanaman berbunga yang berasal dari Genus oxalis, tanaman ini tumbuh liar di pekarangan atau pesawahan. Tanaman ini dipercaya bisa digunakan sebagai tanaman obat.[1] Calincing tanah merup...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (نوفمبر 2019) دوري الدرجة الأولى الليتواني 1929 تفاصيل الموسم دوري الدرجة الأولى الليتواني النسخة 8 البلد ليتواني...

la Guyonneruisseau des brulins Le bassin de la Mauldre et la Guyonne Caractéristiques Longueur 11,9 km [1] Bassin 34 km2 [2] Bassin collecteur la Seine Débit moyen 0,153 m3/s (Mareil-le-Guyon) [2] Organisme gestionnaire COBAHMA (Comité de bassin hydrographique de la Mauldre et de ses affluents)[3] Régime pluvial océanique Cours Source au sein de la forêt de Rambouillet · Localisation Saint-Léger-en-Yvelines · Altitude 180 m · Coordonnées 48° 45′ 10...

Синелобый амазон Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:ЗавропсидыКласс:Пт�...

Questa voce sull'argomento pittori tedeschi è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Bartolomeo Altomonte Bartolomeo Altomonte (Varsavia, 1694 – Sankt Florian, 1783) è stato un pittore austriaco. Biografia Bartolomeo Altomonte è il terzo dei sei figli di Martino Altomonte (germanizzato come Martin Hohenberg), pittore barocco di Napoli chiamato alla corte di Giovanni III Sobieski. Fu allievo di suo padre, e anche di Daniel Gran, maestro baro...

Lambang kota Morges (bahasa Arpitan: Môrges) adalah sebuah kotamadya di Distrik Morges, Kanton Vod, Swiss dan merupakan ibu kota distrik. Komponis dan diplomat terkenal berkebangsaan Polandia, Ignacy Jan Paderewski tinggal di Morges. Kota kembar Gwerzhav, Prancis Rotchfoirt, Belgia Pranala luar http://www.morges.ch Media terkait Morges di Wikimedia Commons Artikel bertopik geografi atau tempat Swiss ini adalah sebuah rintisan. Anda dapat membantu Wikipedia dengan mengembangkannya.lbs

この項目には、一部のコンピュータや閲覧ソフトで表示できない文字が含まれています(詳細)。 数字の大字(だいじ)は、漢数字の一種。通常用いる単純な字形の漢数字(小字)の代わりに同じ音の別の漢字を用いるものである。 概要 壱万円日本銀行券(「壱」が大字) 弐千円日本銀行券(「弐」が大字) 漢数字には「一」「二」「三」と続く小字と、「壱」「�...

2016年美國總統選舉 ← 2012 2016年11月8日 2020 → 538個選舉人團席位獲勝需270票民意調查投票率55.7%[1][2] ▲ 0.8 % 获提名人 唐納·川普 希拉莉·克林頓 政党 共和黨 民主党 家鄉州 紐約州 紐約州 竞选搭档 迈克·彭斯 蒂姆·凱恩 选举人票 304[3][4][註 1] 227[5] 胜出州/省 30 + 緬-2 20 + DC 民選得票 62,984,828[6] 65,853,514[6]...

American designer and artist (born 1959) Maya LinLin in 2023BornMaya Ying Lin (1959-10-05) October 5, 1959 (age 64)Athens, Ohio, U.S.NationalityAmericanEducationYale UniversityKnown forLand art, architecture, memorialsNotable workVietnam Veterans Memorial (1982)Civil Rights Memorial (1989)SpouseDaniel WolfChildren2AwardsNational Medal of Arts Presidential Medal of FreedomWebsitemayalin.com Maya LinTraditional Chinese林瓔Simplified Chinese林璎TranscriptionsStandard Mand...

An American Legal drama series from 2011-2019 This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. Please help by spinning off or relocating any relevant information, and removing excessive detail that may be against Wikipedia's inclusion policy. (August 2018) (Learn how and when to r...

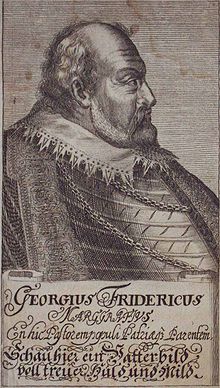

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento nobili tedeschi non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Giorgio Federico di Brandeburgo-AnsbachMargravio di AnsbachIn carica27 dicembre 1543 –25 aprile 1603 PredecessoreGiorgio SuccessoreGioacchino Ernesto Margravio di KulmbachIn carica8 gennaio 1557 –25 aprile 1603 PredecessoreAlberto Alcibiade ...

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources.Find sources: 1994 United States Senate election in Minnesota – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2020) 1994 United States Senate election in Minnesota ← 1988 November 8, 1994 2000 → Nominee Rod Grams Ann Wynia Dean...

2005 live album by Grateful DeadGrateful Dead Download Series Volume 5Live album by Grateful DeadReleasedSeptember 6, 2005RecordedMarch 27, 1988Length142:31LabelGrateful Dead ProductionsGrateful Dead chronology Grateful Dead Download Series Volume 4(2005) Grateful Dead Download Series Volume 5(2005) Grateful Dead Download Series Volume 6(2005) Download Series Volume 5 is a live album by the rock band the Grateful Dead. It includes the complete concert recorded on March 27, 1988, at th...

Mount NonotuckThe northern portion of the Mount Tom Range, with Mount Nonotuck visible to the rightHighest pointElevation827 ft (252 m)Coordinates42°16′48″N 72°37′13″W / 42.28000°N 72.62028°W / 42.28000; -72.62028GeographyLocationHolyoke, MassachusettsParent rangeMount Tom Range / Metacomet RidgeGeologyAge of rock200 MaMountain typefault-block igneousClimbingEasiest routeAuto road Mount Nonotuck, 827 feet (252 m), is the northernmost pea...

Dutch pirate Dirk Chivers (fl. 1694–1699, last name occasionally Shivers) was a Dutch pirate active in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean.[1] Early career Dirk Chivers is first recorded as a crew member of the Portsmouth Adventure, a privateering ship[citation needed], under Captain Joseph Faro (or Farrell) around January 1694. Soon after leaving Rhode Island, Chivers saw action in the Red Sea as Farrell and Henry Every successfully captured two ships in June 1695. On its re...

В Википедии есть статьи о других людях с фамилией Бернстайн. Элмер Бернстайнангл. Elmer Bernstein Основная информация Полное имя Elmer Bernstein Дата рождения 4 апреля 1922(1922-04-04)[1][2][…] Место рождения Нью-Йорк, Нью-Йорк, США[4] Дата смерти 18 августа 2004(2004-08-18)[1]...

1945 film by George Sidney Anchors AweighOriginal promotional posterDirected byGeorge SidneyScreenplay byIsobel LennartBased onYou Can't Fool a Marine1943 story in This Weekby Natalie MarcinProduced byJoe PasternakStarringFrank SinatraKathryn GraysonGene KellyJosé IturbiDean StockwellPamela BrittonRags RaglandBilly GilbertHenry O'NeillCinematographyCharles P. BoyleRobert H. PlanckEdited byAdrienne FazanMusic byGeorgie StollColor processTechnicolorProductioncompaniesMetro-Goldwyn-MayerMGM Car...