Lazar Koliševski

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Фельштинський Юрій Георгійович Народився 7 вересня 1956(1956-09-07) (67 років)Москва, СРСР[1]Країна СРСР СШАДіяльність історикГалузь політична історія[2] і більшовики[2]Alma mater Ратґерський університет і Брандейський університетНауковий ступінь доктор і�...

Championnats du monde de cyclisme sur route 1962 Généralités Sport Cyclisme sur route Lieu(x) Salò et Brescia Date 29 août au 2 septembre 1962 Épreuves 4 Site web officiel Site officiel de l'UCI Navigation Berne 1961 Renaix 1963 modifier Jean Stablinski est devenu champion du monde. Les championnats du monde de cyclisme sur route 1962 ont eu lieu du 29 août au 2 septembre 1962 à Salò et Brescia en Italie. Le championnat du monde du contre-la-montre par équipes fait son apparition. ...

You've Got MailPoster teatrikalSutradaraNora EphronProduserNora EphronLauren Shuler DonnerSkenarioNora EphronDelia EphronBerdasarkanParfumerieoleh Miklós LászlóPemeranTom HanksMeg RyanPenata musikGeorge FentonSinematograferJohn LindleyPenyuntingRichard MarksPerusahaanproduksiWarner Bros.DistributorWarner Bros.Tanggal rilis 18 Desember 1998 (1998-12-18) Durasi119 menitNegaraAmerika SerikatBahasaInggrisAnggaran$65 jutaPendapatankotor$250,821,495 [1] You've Got Mail adalah ...

Alessio II ComnenoRaffigurazione di Alessio II Comneno tratta dal Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum, 1553Basileus dei RomeiIn carica24 settembre 1180 –settembre 1183 PredecessoreManuele I Comneno SuccessoreAndronico I Comneno Nome completoAlexios II Komnēnos NascitaCostantinopoli, 14 settembre 1169 MorteCostantinopoli, settembre 1183 DinastiaComneni PadreManuele I Comneno MadreMaria d'Antiochia ConsorteAgnese di Francia ReligioneCristianesimo ortodosso Alessio II Comneno (in greco ...

Currency of Serbia Dinarдинар (Serbian) DIN 2,000 banknoteDIN 20 coin ISO 4217CodeRSD (numeric: 941)Subunit0.01UnitPluralдинари / dinari (dinars)SymbolDIN / динDenominationsSubunit 1⁄100пара / para (defunct)Banknotes Freq. usedDIN 10, DIN 20, DIN 50, DIN 100, DIN 200, DIN 500, DIN 1,000, DIN 2,000[1] Rarely usedDIN 5,000Coins Freq. usedDIN 1, DIN 2, D...

56°20′29″N 2°47′41″W / 56.341424°N 2.794658°W / 56.341424; -2.794658 This article is missing information about identity of namesake saint. Please expand the article to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (August 2020) St Salvator's CollegeCoat of arms of St Salvator's CollegeFormer namesThe College of the Holy SaviourTypeCollegeActive1450–1747LocationSt Andrews, Fife, ScotlandAffiliationsUniversity of St Andrews St Salva...

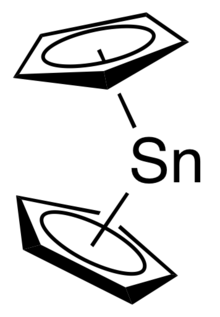

Stannocene Names IUPAC name StannoceneBis(η5-cyclopentadienyl)tin(II) Other names Bis(cyclopentadienyl)tinDi(cyclopentadienyl)tin Identifiers CAS Number 1294-75-3[1] 3D model (JSmol) Interactive image InChI InChI=1S/2C5H5.Sn/c2*1-2-4-5-3-1;/h2*1-5H;/q2*-1;+2Key: CRQFNSCGLAXRLM-UHFFFAOYSA-N SMILES [cH-]1cccc1.[cH-]1cccc1.[Sn+2] Properties Chemical formula C10H10Sn Molar mass 248.900 g·mol−1 Structure[2] Crystal structure orthorhombic Space group Pbcm, No.5...

2009 single by PortisheadChase the TearSingle by PortisheadReleased10 December 2009GenreElectronic rockLength5:15LabelAmnestySongwriter(s)PortisheadProducer(s)PortisheadPortishead singles chronology Magic Doors (2008) Chase the Tear (2009) Chase the Tear is a single released by the band Portishead on 10 December 2009, as a download-only for Human Rights Day to raise money for Amnesty International UK. It reached number 164 in the UK charts,[1] and was later released as a limited editi...

此条目序言章节没有充分总结全文内容要点。 (2019年3月21日)请考虑扩充序言,清晰概述条目所有重點。请在条目的讨论页讨论此问题。 哈萨克斯坦總統哈薩克總統旗現任Қасым-Жомарт Кемелұлы Тоқаев卡瑟姆若马尔特·托卡耶夫自2019年3月20日在任任期7年首任努尔苏丹·纳扎尔巴耶夫设立1990年4月24日(哈薩克蘇維埃社會主義共和國總統) 哈萨克斯坦 哈萨克斯坦政府...

Ця стаття про колишню податкову службу України. Про нову податкову службу див. Державна податкова служба України. Ця стаття використовує голі URL-посилання для посилань на джерела, що може призвести до мертвих посилань[en]. Будь ласка, допоможіть удосконалити цю статтю, зам�...

U.S. commercial and investment banking company House of Morgan redirects here. For the building, see 23 Wall Street. For the Welsh dynasty descended from Morgan Hen, see kings of Morgannwg. J.P. Morgan & Co.Company typeSubsidiaryIndustryInvestment bankingAsset managementPrivate bankingFounded1871; 153 years ago (1871)FounderJ. P. MorganAnthony DrexelHeadquartersNew York City, U.S.Number of employees26,314 (2010)ParentJPMorgan ChaseWebsitewww.jpmorgan.com J.P. Morgan &...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (أبريل 2021) كأس تونس لكرة اليد للرجال معلومات عامة الرياضة كرة اليد انطلقت 1955 البلد تونس المنظم الجامعة التونسية ل...

Voce principale: Eccellenza 2015-2016. Eccellenza Trentino-Alto Adige(DE) Oberliga Trentino-Südtirol2015-2016 Competizione Eccellenza Trentino-Alto Adige Sport Calcio Edizione 25ª Organizzatore FIGC - LNDComitato Regionale Trentino-Alto Adige Luogo Italia Partecipanti 16 Formula 1 Girone all'italiana con play-off Sito web FIGC-BZ Statistiche Incontri disputati 240 Gol segnati 692 (2,88 per incontro) Cronologia della competizione 2014-2015 2016-2017 Manuale Il campionato italiano...

قرية جزيرة جريب - قرية - تقسيم إداري البلد اليمن المحافظة محافظة حجة المديرية مديرية ميدي العزلة عزلة الجزر معلومات أخرى التوقيت توقيت اليمن (+3 غرينيتش) تعديل مصدري - تعديل جزيرة جريب هي إحدى جزر مديرية ميدي التابعة لمحافظة حجة.[1] مراجع وروابط خارجية ^...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Victor. Paul-Émile VictorPortrait d'après photo.FonctionDirecteurExpéditions polaires françaises (en)1947-1976BiographieNaissance 28 juin 1907Genève (Suisse)Décès 7 mars 1995 (à 87 ans)Bora-BoraNom de naissance Paul Eugène VictorNationalités américainefrançaiseFormation École centrale de LyonÉcole nationale de la Marine marchandeActivités Explorateur, écrivain, ethnologue, anthropologue, aviateurConjoint Éliane Victor, Colette VictorEnf...

Indigenous music ofNorth America North American Indian music Aboriginal music of Canada Music of indigenous tribes and peoples Arapaho Blackfeet Dene Innu Inuit Iroquois Kiowa Kwakwaka'wakw Métis Navajo Pueblo Seminole Sioux Yaqui Yuman Types of music List Chicken scratch Ghost Dance Hip hop New Mexico music Opera Peyote song Pow wow Throat singing Instruments Anasazi flute Apache fiddle Clapper stick Native American flute Water drum Awards ceremonies and awards APCMAs NAMAs Grammy Award Jun...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Fantin et Latour. Henri Fantin-LatourAutoportrait (1861),Washington, National Gallery of Art.BiographieNaissance 25 janvier 1836Grenoble (Isère, France)Décès 25 août 1904 (à 68 ans)Buré (Orne, France)Sépulture Cimetière du MontparnasseNom de naissance Ignace Henri Jean Théodore Fantin-LatourPseudonyme Fantin-Latour, Ignace Henri Jean TheodoreNationalité France FrançaiseFormation Petite école de dessin de ParisActivité Peintre, lithographeP�...

فضيلة الشيخ فانيا مبادي عبد الرحيم (بالتاميلية: ஃபனியா முபாடி அப்துர் ரஹீம்) معلومات شخصية الميلاد 7 مايو 1933 [1] فانيمبدي[1] الوفاة 19 أكتوبر 2023 (90 سنة) [2] المدينة المنورة مكان الدفن البقيع مواطنة الراج البريطاني (1933–1947) الهند (...

この記事は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。 出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。(このテンプレートの使い方)出典検索?: 正力亨 – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii · J-STAGE · NDL · dlib.jp · ジャパンサーチ · TWL (2024年4月) しょうりき とおる正力 亨生誕 (1918-10-24) 1918年10月24�...

Seat of state of a potentate or dignitary This article is about royal and ecclesiastical thrones. For other uses, see Throne (disambiguation). A drawing of a throne, on a dais under a baldachin A throne is the seat of state of a potentate or dignitary, especially the seat occupied by a sovereign (or viceroy) on state occasions; or the seat occupied by a pope or bishop on ceremonial occasions.[1] Throne in an abstract sense can also refer to the monarchy itself, an instance of metonymy...