Gittern

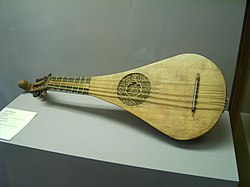

The gittern was a relatively small gut-strung, round-backed instrument that first appeared in literature and pictorial representation during the 13th century in Western Europe (Iberian Peninsula, Italy, France, England). It is usually depicted played with a quill plectrum,[1] as can be seen clearly beginning in manuscript illuminations from the thirteenth century. It was also called the guiterna in Spain, guiterne or guiterre in France, the chitarra in Italy and Quintern in Germany.[2] A popular instrument with court musicians, minstrels, and amateurs, the gittern is considered an ancestor of the modern guitar and other instruments like the mandore, bandurria and gallichon.[3][4] From the early 16th century, a vihuela-shaped (flat-backed) guitarra began to appear in Spain, and later in France, existing alongside the gittern. Although the round-backed instrument appears to have lost ground to the new form which gradually developed into the guitar familiar today, the influence of the earlier style continued. Examples of lutes converted into guitars exist in several museums, while purpose-built instruments like the gallichon utilised the tuning and single string configuration of the modern guitar. A tradition of building round-backed guitars in Germany continued to the 20th century with names like Gittar-Laute and Wandervogellaute. Up until 2002, there were only two known surviving medieval gitterns,[5][6] one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see external links), the other in the Wartburg Castle Museum. A third was discovered in a medieval outhouse in Elbląg, Poland.[6][7] StructureGittern (right) depicted in a c. 1322 fresco scene from the life of St. Martin of Tours. The instrument on the left is a set of aulos. Juan Oliver's c.1330 painting at Pamplona Cathedral, showing a musician playing a gittern. The back, neck and pegbox were probably usually carved from one piece of timber. Occurring less rarely later in the 15th century, the back was built up from a number of thin tapered ribs joined at the edges, as was characteristic of the lute. Unlike the sharp corner joining the body to the neck seen in the lute, the gittern's body and neck either joined in a smooth curve or straight line. The sickle, or occasional gentle arc pegbox, made an angle with the neck of between 30 and 90 degrees. Unlike the lute, most pegboxes on gitterns ended in a carving of a human or animal head. Most gitterns were depicted as having three or (more commonly) four courses of double strings. There are also references to some five course gitterns in the 16th century. Although there is not much direct information concerning gittern tuning, the later versions were quite possibly tuned in fourths and fifths like the mandore a few decades later. Frets were represented in a few depictions (mainly Italian and German), although apparently absent in most French, Spanish and English depictions. The gittern's sound hole was covered with a rosette (a delicate wood carving or parchment cutting), similar to the lute. The construction resembles other bowed and plucked instruments, including the rebec, Calabrian and Byzantine lyra, gǎdulka, lijerica, klasic kemençe, gudok and cobza. These have similar shapes, a short neck, and like the gittern are carved out of a single block of wood. Relationship between gittern, the citole, lute and guitar familyBy 1575, the German quintern included guitar-shaped instruments. Section from Sebastian Virdung's 1511 book, Musica getuscht und angezogen. (Top left) lute, (right) viol, (bottom) gittern Some have pointed out that there have been errors in scholarship (starting in the 19th century) which led to the gittern being called mandore and vice versa,[8] and similar confusion with the citole.[8] As a result of this uncertainty, many modern sources refer to gitterns as mandoras, and to citoles as gitterns. A number of modern sources have also claimed the instrument was introduced to Europe from the Arabic regions in a manner similar to the lute, but actual historical data supporting this theory is rare, ambiguous, and may suggest the opposite. The various regional names used (including the Arabic) appear derived over time from a Greco-Roman (Vulgar Latin) origin, although when and how this occurred is presently unknown.[citation needed] It is possible the instrument existed in Europe during a period earlier than the Arabic conquests in the Iberian peninsula, with the names diverging alongside the regional evolution of European languages from Latin following the collapse of the Roman Empire (compare Romance languages). While the name of the lute (Portuguese alaúde, Spanish laud, from Arabic al-ʿūd), and the instrument itself has been interpreted as being of Arabic/Persian origin, the gittern does not appear in historical Arabic source material to support what can only be speculation.[citation needed] Etymology and identityOne of the three "gitterns" may not be Instrument in the Metropolitan Museum of Arts labeled a gittern in James Tyler's book, The Early Mandolin. The museum catalog, Medieval Art from Private Collections: A Special Exhibition at the Cloisters said that it probably wasn't a gittern but a bowed instrument, possibly a rebec, but one with five strings instead of the rebec's normal three.[9] The gittern had faded so completely from memory in England that identifying the instrument proved problematic for 20th-century early music scholarship. It was assumed the ancestry of the modern guitar was only to be discovered through the study of flat-backed instruments. As a consequence, what is now believed to be the only known surviving medieval citole was until recently labelled a gittern. In 1977, Lawrence Wright published his article The Medieval Gittern and Citole: A Case of Mistaken Identity. in issue 30 of the Galpin Society Journal; with detailed references to primary historical source material revealing the gittern as a round-backed instrument - and the so-called 'Warwick Castle gittern' (a flat-backed instrument) as originally a citole. Wright's research also corresponded with observations about the origins of the flat-backed guitarra made by 16th-century Spanish musicologist Juan Bermudo. With this theoretical approach, it became possible for scholars to untangle previously confusing and contradictory nomenclature. Because of the complex nature of the subject, the list and links below should assist in further reading.

The modern Portuguese equivalent to the 'Spanish guitar' is still generally known as viola (violão in Brazil - literally large viola), as are some smaller regional related instruments. Portuguese 'viola' (like Italian), is cognate with Spanish 'vihuela'. Unlike in Spain, all these instruments traditionally used metal strings until the advent of modern nylon strings. While the modern violão is now commonly strung with nylon (although steel string variations still exist), in Portugal musicians differentiate between the nylon strung version as guitarra clássica and the traditional instrument as viola de Fado, reflecting the historical relationship with fado music. While the English and Germans are considered to have borrowed their names from the French,[10] Spanish "guitarra", Italian "chitarra", and the French "guitarre" are believed ultimately to be derived from the Greek "kithara"[10] - although the origins of the historical process which brought this about are not yet understood, with very little actual evidence other than linguistic to explore. Role in literatureCantigas of Santa MariaPicture from the Cantigas of Santa Maria showing two musicians with gitterns Gittern played by an angel, Cathedral Saint Julien du Mans, France, c. 1325 In Spanish literature, the 13th-century Cantigas de Santa Maria with its detailed colored miniature illustrations depicting musicians playing a wide variety of instruments is often used for modern interpretations - the pictures reproduced and captioned, accompanied by claims supporting various theories and commenting on the instruments. None of the surviving four manuscripts contain captions (or text in the poems) to support observations other than the gittern appears to have had equal status with other instruments. Although social attitudes towards instruments like the lute, rebec, and gittern may have changed in Spain much later with the cultural impact of the Reconquista - what is recorded in the Cantigas indicates the opposite during this period of history. Far from being considered an example of Islamic culture, the instrument was used for one occasion to illustrate principles of Christian religious doctrine. French theologian Jean Gerson compared the four cardinal virtues to "la guiterne de quatre cordes" (the gittern of four strings). Italian statesman and poet Dante Alighieri, referring to the qualities (and possibly the structure) of the gittern, said, "...just as it would be a blameworthy operation to make a spade of a fine sword or a goblet of a fine chitarra." Guillaume de MachautHowever, 14th-century French composer Guillaume de Machaut in his poem Prise d'Alexandrie: 1150 "Lutes, moraches and guiterne / were played in taverns", notes a secular role away from religious references or royal and ducal courts. Geoffrey Chaucer Chaucer also mentions the gittern in the Canterbury Tales (late 14th century) being played by people who frequent taverns. In The Miller's Tale, Absalom serenades a woman outside her window:[11] Now was ther of that chirche a parish clerk, And his The Cooks Tale.,[11] Al konne he pleye on gyterne or ribible (all can he play on gittern or rebab).[13] Other written recordsPraetorius, commenting on a dual-purpose social role, "..in Italy, the Ziarlatini and Salt' in banco use them for simple strummed accompaniments to their villanelle and other vulgar, clownish songs. (These people are something like our comedians and buffoons.) However, to use the (chiterna) for the beautiful art-song of a good professional singer is a different thing altogether." The gittern often appeared during the 14th to early 15th century in the inventories of several courts. Charles V of France's court recorded four, including one of ivory, while the Italian courts of Este and Ferrara recorded the hiring of gittern (chitarra) masters. ResourcesEarly Music Instrument Database - Gittern References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Gittern.

|

||||||||||||