Frank Nash

| |||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

العلاقات البحرينية التشادية البحرين تشاد البحرين تشاد تعديل مصدري - تعديل العلاقات البحرينية التشادية هي العلاقات الثنائية التي تجمع بين البحرين وتشاد.[1][2][3][4][5] مقارنة بين البلدين هذه مقارنة عامة ومرجعية للدولتين: وجه المقارنة البح�...

العلاقات الجزائرية الباربادوسية الجزائر باربادوس الجزائر باربادوس تعديل مصدري - تعديل العلاقات الجزائرية الباربادوسية هي العلاقات الثنائية التي تجمع بين الجزائر وباربادوس.[1][2][3][4][5] مقارنة بين البلدين هذه مقارنة عامة ومرجعية للدول�...

1855 naval battle Battle of the LeotungPart of Piracy in AsiaAn 1890 map of the Pearl River Delta, Leotung is at the center right.DateAugust 19, 1855LocationGulf of Leotung, ChinaResult British victoryBelligerents United Kingdom Chinese PiratesCommanders and leaders Charles Turner Edward W. Vansittart unknownStrength 1 brig1 steamer 2 lorchas~37 war-junksCasualties and losses none1 brig damaged1 steamer damaged ~300 killed or wounded2 lorchas sunk6 war-junks sunk~5 war-junks damaged vtePiracy...

British news and current affairs programme For other uses, see Nationwide (Irish TV programme) and Nationwide (Australian TV programme). NationwideNationwide's mandala logo, introduced in 1972.GenreNews and Current affairsCreated byDerrick Amoore[1]Presented by Michael Barratt (1969–1977)[1] Bob Langley (1970–1972) Esther Rantzen (1970–1972) Bob Wellings (1971–1980) Bernard Falk (1972–1978) Valerie Singleton (1972–1978) Richard Stilgoe (1972–1978) Frank Bough...

2002 film by Phil Weinstein Wolf Quest redirects here. For the video game, see WolfQuest. Aniu redirects here. Not to be confused with Ainu. Balto II: Wolf QuestDVD release coverDirected byPhil WeinsteinScreenplay byDev RossProduced byPhil WeinsteinStarring Jodi Benson David Carradine Lacey Chabert Mark Hamill Maurice LaMarche Peter MacNicol Charles Fleischer Rob Paulsen Nicolette Little Melanie Spore Kevin Schon Edited by Jay Bixsen Ken Solomon Music byAdam Berry (score)Amanda McBroomMichele...

Untuk the Madonna song, lihat Material Girl. Untuk other uses, lihat Material girl (disambiguation). Material GirlsTheatrical release posterSutradaraMartha CoolidgeProduserMilton KimTim WesleyMark MorganGuy OsearyHilary DuffHaylie Duff[1]Susan DuffEva LaRueDavid FaigenblumDitulis olehJohn QuaintanceJessica O'Toole Amy RardinPemeranHilary DuffHaylie DuffAnjelica HustonLukas HaasMaria Conchita AlonzoBrent SpinerPenata musikJennie MuskettSinematograferJohnny E. JensenPenyuntingStev...

Railway station in Bihar, India Mansi JunctionIndian Railways stationIndian Railways logoGeneral informationLocationNH 31, Industrial Area, Mansi, Khagaria district, Bihar IndiaCoordinates25°30′33″N 86°33′18″E / 25.5092°N 86.5551°E / 25.5092; 86.5551Elevation42.445 metres (139.26 ft)Owned byIndian RailwaysOperated byEast Central RailwaysPlatforms3Tracks4ConstructionStructure typeStandard on groundParkingYesAccessible AvailableOther informationStat...

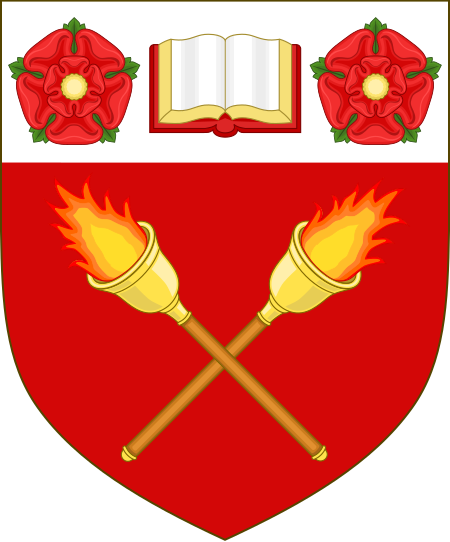

College of University of Oxford Harris Manchester CollegeUniversity of OxfordHarris Manchester College Arlosh QuadArms: Gules two torches inflamed in saltire proper, on a chief argent, between two roses of the field barbed and seeded, an open book also proper. LocationMansfield Road (map)Coordinates51°45′21″N 1°15′07″W / 51.755758°N 1.252044°W...

Wholly owned subsidiary of ISRO ISRO Propulsion Complex (IPRC)Location of Mahendragiri in Tirunelveli districtAgency overviewJurisdictionDepartment of SpaceHeadquartersMahendragiri, Tirunelveli district8°16′57″N 77°33′57″E / 8.2825479°N 77.5658637°E / 8.2825479; 77.5658637Employees600+Annual budgetSee the budget of ISROAgency executiveJ. Asir Packiaraj [1], DirectorParent agencyISROWebsitewww.iprc.gov.in The ISRO Propulsion Complex (IPRC), located a...

Orang AzerbaijanAzərbaycanlılar, Azərbaycan türkləri آذربایجانی ها ، ترک های آذربایجانی Penari tradisional AzerbaijanJumlah populasisekitar 20 juta hingga 50 juta jiwaDaerah dengan populasi signifikan Iran12 hingga 18 juta[1][2][3][4][5] Azerbaijan8.238.672[6][7] Turki800.000[8] Rusia622.000[9] Georgia284.761[10] Kazakhstan78.300[11] Jerm...

Protein-coding gene in the species Homo sapiens ACVR2BAvailable structuresPDBOrtholog search: PDBe RCSB List of PDB id codes2QLU, 4FAO, 2H62IdentifiersAliasesACVR2B, ACTRIIB, ActR-IIB, HTX4, activin A receptor type 2BExternal IDsOMIM: 602730 MGI: 87912 HomoloGene: 863 GeneCards: ACVR2B Gene location (Human)Chr.Chromosome 3 (human)[1]Band3p22.2Start38,453,890 bp[1]End38,493,142 bp[1]Gene location (Mouse)Chr.Chromosome 9 (mouse)[2]Band9|9 F3Start119,231,184 ...

Major League Baseball logos and uniforms Team photo of the 1901 Boston Americans, the franchise's first season competing in the American LeagueThe logos and uniforms of the Boston Red Sox have gone through a limited number of changes throughout the history of the team. Logo Boston Americans logo used from 1901 to 1907 Boston Red Sox logo used in 1908 Uniforms Home uniforms Manny Ramirez in 2007 wearing the current primary home uniformDick McAuliffe in 1974 wearing the 1973–78 primary home u...

Genus of birds This article is about the two species of gull. For other uses, see Kittiwake (disambiguation). Kittiwake Black-legged kittiwakes, Rissa tridactyla, nesting on the Farne Islands, Northumberland, UK The call of a kittiwake, recorded on Skomer Island, Pembrokeshire, Wales Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Aves Order: Charadriiformes Family: Laridae Subfamily: Larinae Genus: RissaStephens, 1826 Type species Rissa brunnichii[1&...

Disambiguazione – Se stai cercando altri significati, vedi Supercoppa italiana 2016 (disambigua). Voce principale: Supercoppa italiana. Supercoppa italiana 2016Supercoppa TIM 2016 Competizione Supercoppa italiana Sport Calcio Edizione 29ª Organizzatore Lega Serie A Date 23 dicembre 2016 Luogo QatarDoha Partecipanti 2 Formula gara unica Impianto/i Stadio Jassim bin Hamad Risultati Vincitore Milan(7º titolo) Secondo Juventus Statistiche Gol segnati 2 Pubblico 11 356 Cronologia d...

此條目可参照英語維基百科相應條目来扩充。 (2021年10月13日)若您熟悉来源语言和主题,请协助参考外语维基百科扩充条目。请勿直接提交机械翻译,也不要翻译不可靠、低品质内容。依版权协议,译文需在编辑摘要注明来源,或于讨论页顶部标记{{Translated page}}标签。 国际调查记者同盟International Consortium of Investigative Journalists成立時間1997年總部华盛顿哥伦比亚特区 地址�...

Town in Massachusetts, United StatesBillerica, MassachusettsTownBillerica Public Library FlagSealLogoMotto: America's Yankee Doodle Town[1]Location in Middlesex County in MassachusettsBillerica, MassachusettsLocation in the United StatesCoordinates: 42°33′30″N 71°16′10″W / 42.55833°N 71.26944°W / 42.55833; -71.26944CountryUnited StatesStateMassachusettsCountyMiddlesexRegionNew EnglandSettled1652IncorporatedMay 29, 1655Named forBillericayGovern...

卡雷尔·乌尔班内克出生1941年3月22日 (83歲)博伊科維采 職業政治人物 政党捷克和摩拉维亚共产党、捷克斯洛伐克共產黨 卡雷尔·乌尔班内克(捷克語:Karel Urbánek;1941年3月22日—),捷克斯洛伐克共产党领导人之一,最后一任捷共中央总书记(此后捷共的最高领导人改称主席)。 生平 1963年,加入捷克斯洛伐克共产党。1989年11月24日,接任捷共中央總書記...

威廉·理查德·托尔伯特William Richard Tolbert第20任利比里亚总统任期1971年7月23日—1980年4月12日副总统空缺(1971–1972)詹姆斯·爱德华·格林(英语:James Edward Greene)(1972–1977)本尼·迪·华纳(英语:Bennie Dee Warner)(1977–1980)前任威廉·瓦坎納拉特·沙德拉奇·杜伯曼继任塞缪尔·多伊第23任利比里亚副总统任期1952年1月1日—1971年7月23日总统威廉·瓦坎納拉特·沙德拉奇·杜�...

Novelist, short story writer, educator Walter Van Tilburg ClarkBorn(1909-08-03)August 3, 1909East Orland, Maine, USDiedNovember 10, 1971(1971-11-10) (aged 62)Virginia City, Nevada, USOccupationWriter, college teacherEducationUniversity of Nevada, Reno (BA, MA)GenresNovel, short storyYears active1932–1971Notable worksThe Ox-Bow Incident, The Watchful Gods and Other StoriesNotable awardsO. Henry Prize, Nevada Writer's Hall of FameSpouseBarbara Frances Morse (d. 1969)Children2[1&...

Il piano Andinia è una teoria del complotto sulla colonizzazione e conversione religiosa dell'Argentina da parte della ebraismo tramite massicce ondate migratorie, che nel tempo avrebbero procurato la maggioranza democratica agli ebrei immigrati e la conseguente finalità ultima di costituire uno Stato ebraico. Indice 1 Storia 2 Implicazione del sionismo internazionale 3 Note 4 Bibliografia 5 Voci correlate Storia Le prime ondate migratorie vennero dall'Europa e furono inizialmente costituit...