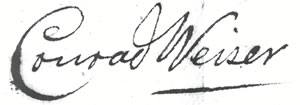

Conrad Weiser Homestead

The Conrad Weiser Homestead was the home of Johann Conrad Weiser, who enlisted the Iroquois on the British side in the French and Indian War. The home is located near Womelsdorf, Berks County, Pennsylvania in the United States. A designated National Historic Landmark, it is currently administered as a historic house museum by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. The historic site was established in 1923 to preserve an example of a colonial homestead and to honor Weiser, an important figure in the settlement of the colonial frontier. The site includes period buildings and an orientation exhibit on a 26-acre (110,000 m2) landscaped park designed by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. The park features walking and hiking paths, meadows, groves and a pond. The park contains statues of Conrad Weiser and of Shikellamy, an Onondaga chief who befriended Weiser and helped him keep the peace on the frontier of colonial Pennsylvania. The Friends of the Conrad Weiser Homestead assist in operating the programs. The house was built in 1729 of native limestone. It was expanded several times over the years but it does include an original single room with fireplace and bake oven and a second room that Weiser added to his home in 1750. The home is decorated with many of the furnishings and household tools that were most common during the frontier era. A family cemetery behind the house is the final resting place of Weiser, his wife Anna and many friendly Indian Chiefs. Life of Conrad WeiserEarly yearsConrad Weiser was born in 1696 in the small village of Affstätt in Herrenberg, in the Duchy of Württemberg (now part of Germany), where his father (also John Conrad Weiser), as a member of the Württemberg Blue Dragoons, was stationed. Soon after Conrad's birth, his father received a discharge from the Blue Dragoons and moved back to the family ancestral home of Gross Aspach. Fever claimed the life of his mother, Anna Magdalena, in 1709 after war, pestilence, and an unusually cold and long winter ravaged the lands. Wallace notes that Conrad Weiser (senior) wrote for his children, "Buried beside Her Ancestors, she was a god-fearing woman and much loved by Her neighbors. Her motto was Jesus I live for thee, I die for thee, thine am I in life and death." His family moved to the frontier town of Schoharie, New York by 1710 at the expense of Queen Anne. There the German immigrants were placed into indentured servitude, as per a signed agreement, to burn tar to pay for the journey. When he was only 16, Weiser's father agreed to a chief's proposal for him to live with the Mohawks in the upper Schoharie Valley. During his stay with them in the winter and spring of 1712–1713, Weiser endured hardships of cold, hunger and homesickness, but he learned a great deal about the Mohawk language and the customs of the Iroquois. Conrad Weiser returned to his own people towards the end of July 1713. On November 22, 1720, at the age of 24, he married a young German girl, Anna Eve Feck. In 1723 the couple followed the Susquehanna River south and settled their young family on a farm in Tulpehocken near present-day Reading, Pennsylvania. The couple had fourteen children, but only seven reached adulthood. Service to Pennsylvania Weiser's colonial service began in 1731. The Iroquois sent Shikellamy, an Oneida chief, as an emissary to other tribes and the British. Shikellamy lived on the Susquehanna River at Shamokin village, near present-day Sunbury, Pennsylvania and Shikellamy State Park. An oral tradition holds that Weiser met Shikellamy while hunting. In any case, the two became friends. When Shikellamy traveled to Philadelphia for a council with the Province of Pennsylvania, he brought Weiser with him. The Iroquois trusted him and considered him an adopted son of the Mohawks. Weiser impressed the Pennsylvania governor and council, which thereafter relied heavily on his services. Weiser also interpreted in a follow-up council in Philadelphia in August, 1732. During the treaty in Philadelphia of 1736, Shikellamy, Weiser and the Pennsylvanians negotiated a deed whereby the Iroquois sold the land drained by the Delaware River and south of the Blue Mountains. Since the Iroquois had never until then laid claim to this land, this purchase represented a significant swing in Pennsylvanian policy toward the Native Americans. William Penn had never taken sides in disputes between tribes, but by this purchase, the Pennsylvanians were favoring the Iroquois over the Lenape. Along with the Walking Purchase of the following year, his treaty exacerbated Pennsylvania-Lenape relations. The results of this policy shift would help induce the Lenape to side with the French during the French and Indian Wars, which would result in many colonial deaths. It did, however, help induce the Iroquois to continue to side with the British over the French. During the winter of 1737, Weiser attempted to broker a peace between southern tribes and the Iroquois. Having survived high snow, freezing temperatures and starvation rations during the six-week journey to the Iroquois capital of Onondaga, he managed to convince the Iroquois not to send any war parties in the spring, but he failed to convince them to send emissaries to parlay with the southern tribes. Impressed with his fortitude in the pursuit of peace, the Iroquois named Weiser "Tarachiawagon", or "Holder of the Heavens." Spill-over violence from a war between the Iroquois and southern tribes such as the Catawba would have drawn first Virginia, and then Pennsylvania, into conflict with the Iroquois. Therefore, this peace-brokering had a profound effect on Native American/colonial relations. In 1742, he interpreted at a treaty with the Iroquois at Philadelphia, at which time they were paid for the land purchased in 1736. During this council, the Onondaga chief Canasatego castigated the Lenape for engaging in land sales, and ordered them to remove their settlements to either the Wyoming Valley or Shamokin village. This accelerated the Lenape migration to the Ohio Valley, which had begun as early as the 1720s. There, they would be positioned to trade with the French, and launch raids as far east as the Susquehanna River during the French and Indian Wars. In 1744, Weiser acted as the interpreter for the Treaty of Lancaster, between representatives of the Iroquois and the colonies of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. During the final day of the treaty, on 1744-07-04, Canasatego, the Onondaga chief, spoke of the Iroquois concepts of political unity: "Our wise forefathers established Union and Amity between the Five Nations. This has made us formidable; this has given us great Weight and Authority with our neighboring Nations. We are a powerful Confederacy; and by your observing the same methods, our wise forefathers have taken, you will acquire such Strength and power. Therefore whatever befalls you, never fall out with one another." Benjamin Franklin printed this speech, which influenced American concepts of political unity. Significantly, after the Treaty of Lancaster, both Virginia and Pennsylvania acted as if the Iroquois had sold them the rights to the Ohio Valley, but the Iroquois did not believe they had done so. In 1748, Pennsylvania sent Conrad Weiser to Logstown, a council and trade village on the Ohio River. Here he held council with chiefs representing 10 tribes, including Lenape and Shawnee, and the Iroquois. He arrived at a treaty of friendship between Pennsylvania and these tribes. Threatened by this development and the continued activity of British traders in the Ohio valley, the French redoubled their diplomatic efforts and began to build a string of forts, culminating in Fort Duquesne at present-day Pittsburgh, in 1754. In 1750, he traveled again to Onondaga, he found the political dynamics in the Six Nations had shifted. Canasatego, always pro-British, had died. Several Iroquois tribes were leaning toward the French, although the Mohawks remained pro-British. Early in the summer of 1754, on the eve of the French and Indian War, Weiser was a member of a Pennsylvania delegation to Albany. London had invoked the meeting, hoping to win assurances of Iroquois support in the looming war with the French. Present were representatives of the Iroquois and seven colonies. Because of divisions within both the British and Native American ranks, the council did not result in the treaty of support that the crown desired. Instead, each colony made the best deal it could with individual Iroquois leaders. Weiser was able to negotiate one of the more successful, in which some lower-level chiefs deeded to the colony most of the land remaining in present-day Pennsylvania, including the southwestern part, still claimed by Virginia.  In 1756, Weiser was appointed along with Ben Franklin to construct a series of forts between the Delaware River and the Susquehanna River. In the fall of 1758, Weiser attended a council at Easton. Representation included leaders from Pennsylvania, the Iroquois and other Native American tribes. Weiser helped smooth over the tense meeting. With the Treaty of Easton, the tribes in the Ohio Valley agreed to abandon the French. This collapse of Native American support was a factor in the French decision to demolish Fort Duquesne and withdraw from the Forks of the Ohio. Throughout this decades-long career, Weiser's knowledge of Native American languages and culture made him a key player in treaty negotiations, land purchases, and the formulation of Pennsylvania's policies towards Native Americans. Because of his early experiences with the Iroquois, Weiser was inclined to be sympathetic to their interpretation of events, as opposed to the Lenape or the Shawnee. This may have exacerbated Pennsylvanian-Lenape/Shawnee relations, with bloody consequences in the French and Indian Wars. Nevertheless, for many years, he helped to keep the powerful Iroquois, or Six Nations, allied with the British as opposed to the French. This important service contributed to the continued survival of the British colonies and the eventual victory of the British over the French in the French and Indian Wars. Conrad Weiser HomesteadThe Conrad Weiser Homestead is a Pennsylvania state historic site located in Womelsdorf, Berks County, Pennsylvania which interprets the life of Conrad Weiser. Weiser was an 18th-century German immigrant who served as an Indian interpreter and who helped coordinate Pennsylvania's Indian policy. He played a major role in the history of colonial Pennsylvania. The Conrad Weiser Homestead is located on Rt. 422, within easy driving distance of Philadelphia, Lancaster, Hershey and Harrisburg. The Conrad Weiser Homestead includes period buildings, and a new orientation exhibit, on a 26-acre (110,000 m2) Olmsted-designed landscaped park. Conrad Weiser’s historical contributions to Pennsylvania simply cannot be overlooked. Weiser was predominantly responsible for negotiating every major treaty between the colonial settlers in Pennsylvania and the Iroquois Nations from 1731 until 1758. In addition to serving as one of the most knowledgeable and successful liaisons between the Indian and the colonist, Weiser was chiefly responsible for both the settlement of the town of Reading, Pennsylvania and the establishment of Berks County. Finally, in 1755, Weiser organized a local militia to quell Indian uprisings during the American phase of the Seven Years' War, and was appointed Colonel of the First Battalion of the Pennsylvania Regiment a year later. Exempting some Berks County locals and various individuals with genealogical ties to this man, few are conscious about the relevance, let alone the existence, of Conrad Weiser. Weiser was born in Astaat, Germany in 1696. His family migrated to America in 1710, settling in New York State. It was in this vicinity where he initially gained contact with the Iroquois Nations. At the age of fifteen he voluntarily decided to live amidst the Mohawk tribe of the Iroquois. Conrad attained significant knowledge of not only the language but also the customs and traditions of the Mohawk tribe, which proved invaluable later in his career. For example, Weiser was one of the few Indian/Colonial interpreters who comprehended the overwhelming significance of the use of Wampum in conducting matters of diplomacy with the Iroquois. Weiser moved to the Tulpehocken area in Pennsylvania in 1729, erecting a house upon a farmstead that would eventually contain 890 acres (3.6 km2) of land. Weiser’s knowledge of the Iroquois was immediately employed, as an Oneida Iroquois, Shikellamy, enlisted Weiser’s abilities as a diplomat to negotiate a series of land ownership treaties between the Pennsylvania colonists and the Indians. Weiser was able to maintain fairly stable relations between the Pennsylvania government and the Iroquois Nation during the 1730s and 1740s. Weiser’s success in mediating Indian/Colonial politics established a tremendous ethos of credibility in the eyes of the Pennsylvania Government. Weiser was appointed Lancaster County Magistrate in 1741, thrusting him into his first “official” role in colonial government. He continued to negotiate territorial matters with the Indians in this position. Then in 1748, Weiser was named one of the commissioners of the town of Reading, in which he bought a plot of land and built a second house. Weiser made several journeys to New York and Central Pennsylvania to attend to matters of Iroquois diplomacy. However, by 1752, Weiser had grown rather exhausted in negotiating with the Indians, and decided to attend to local affairs. Weiser desired to establish a separate county from Lancaster in which the town of Reading would be located. His wish was granted, as the county of Berks was created in 1752. Additionally, Weiser was appointed the county’s first justice of the peace. The American segment of the Seven Years' War erupted in 1754. An incident in 1755 known as the “Penn’s Creek Massacre” left several colonials dead and many others missing in the wake of Indian attacks in northern Pennsylvania. In response to this uprising, Weiser was placed in charge of a local militia in the Tulpehocken region. Then in 1756, Weiser was appointed Colonel of the First Pennsylvania Regiment. Until 1758, he spent most of his time riding between Forts Northkill, Lebanon, and Henry in Berks County as well as other forts under his charge. Weiser conducted his final substantial contribution to Indian/Colonial diplomacy in 1758, negotiating the Treaty of Easton, which concluded the vast majority of Indian insurrection in the eastern third of Pennsylvania. He retired to his house in Reading after completion of this treaty and expired in 1760. Weiser’s body currently resides in a family burial plot to the west of what was believed to have been his house in the Tulpehocken area. Other careersBetween 1734 and 1741, Weiser became a follower of Conrad Beissel, a German Seventh Day Baptist preacher. For six years, he lived at the monastic settlement, Ephrata Cloister, in the Ephrata Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. His wife lived there only a few months before returning to their farm. Weiser would visit her frequently enough, however, to father four more children. In addition, he took leaves of absence for diplomatic duties, such as those in 1736 and 1737. Weiser left the cloister in 1741 after becoming disenchanted with the leadership of Beissel and returned to the Lutheran faith of his father. In addition, he followed a mixed career as a farmer, land owner and speculator, tanner, and merchant. He created the plan for the city of Reading in 1748, was a key figure in the creation of Berks County in 1752 and served as its Justice of the Peace until 1760. Conrad was also teacher and a lay minister of the Lutheran Church, and founded Trinity Church in Reading. In 1756, during the French and Indian War, the Lenape began with raids into central Pennsylvania. As Pennsylvania organized a militia, Conrad was made a Lt. Colonel. Working with Benjamin Franklin, he planned and established a series of forts between the Delaware and Susquehanna Rivers. When General Forbes evicted the French from Fort Duquesne in 1758, the threat subsided. Possible museum closureIn 2008, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC), proposed to close this and several other historic properties because of a budget deficit and relatively few paying visitors.[4] Funding was cut in 2009, and several buildings closed.[5] Since 2012, the buildings are opened on the first Sunday of every month, based on an agreement between the PHMC and the site's Friends.[6] The park areas are open from dawn to dusk every day. See also

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Conrad Weiser Homestead. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||