Common kestrel

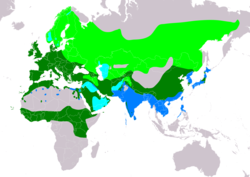

The common kestrel (Falco tinnunculus), also known as the European kestrel, Eurasian kestrel or Old World kestrel, is a species of predatory bird belonging to the kestrel group of the falcon family Falconidae. In the United Kingdom, where no other kestrel species commonly occurs, it is generally just called the "kestrel".[2] This species occurs over a large native range. It is widespread in Europe, Asia and Africa, as well as occasionally reaching the east coast of North America.[3] It has colonized a few oceanic islands, but vagrant individuals are generally rare; in the whole of Micronesia for example, the species was only recorded twice each on Guam and Saipan in the Marianas.[4][5][6] TaxonomyThe common kestrel was formally described in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the current binomial name Falco tinnunculus.[7] Linnaeus specified the type location as Europe but restricted this to Sweden in 1761.[8][9] The genus name is Late Latin from falx, falcis, a sickle, referencing the claws of the bird.[10] The species name tinnunculus is Latin for "kestrel" from "tinnulus", "shrill".[11] The Latin name tinnunculus had been used by the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner in 1555.[12] The word "kestrel" is derived from the French crécerelle which is diminutive for crécelle, which also referred to a bell used by lepers. The word is earlier spelt 'c/kastrel', and is evidenced from the 15th century.[13] The kestrel was once used to drive and keep away pigeons.[14] Archaic names for the kestrel include windhover and windfucker, due to its habit of beating the wind (hovering in air).[13] This species is part of a clade that contains the kestrel species with black malar stripes, a feature which apparently was not present in the most ancestral kestrels. They seem to have radiated in the Gelasian (Late Pliocene,[15] roughly 2.5–2 mya, probably starting in tropical East Africa, as indicated by mtDNA cytochrome b sequence data analysis and considerations of biogeography.[16] A molecular phylogenetic study published in 2015 found that the common kestrel's closest relatives were the spotted kestrel Falco moluccensis and the Nankeen kestrel Falco cenchroides.[17] The rock kestrel (F. rupicolus), previously considered a subspecies, is now treated as a distinct species.[18] The lesser kestrel (F. naumanni), which much resembles a small common kestrel with no black on the upperside except wing and tail tips, is probably not very closely related to the present species, and the American kestrel (F. sparverius) is apparently not a true kestrel at all.[16] Both species have much grey in their wings in males, which does not occur in the common kestrel or its close living relatives but does in almost all other falcons. Subspecies  Eleven subspecies are recognised.[18] Most differ little, and mainly in accordance with Bergmann's and Gloger's rules. Tropical African forms have less grey in the male plumage.[4]

The common kestrels of Europe living during cold periods of the Quaternary glaciation differed slightly in size from the current population; they are sometimes referred to as the paleosubspecies F. t. atavus (see also Bergmann's rule). The remains of these birds, which presumably were the direct ancestors of the living F. t. tinnunculus (and perhaps other subspecies), are found throughout the then-unglaciated parts of Europe, from the Late Pliocene (ELMA Villanyian/ICS Piacenzian, MN16) about 3 million years ago to the Middle Pleistocene Saalian glaciation which ended about 130,000 years ago, when they finally gave way to birds indistinguishable from those living today. Some of the voles the Ice Age common kestrels ate—such as European pine voles (Microtus subterraneus)—were indistinguishable from those alive today. Other prey species of that time evolved more rapidly (like M. malei, the presumed ancestor of today's tundra vole M. oeconomus), while yet again others seem to have gone entirely extinct without leaving any living descendants—for example Pliomys lenki, which apparently fell victim to the Weichselian glaciation about 100,000 years ago.[22][23] DescriptionThe common kestrel measures 32–39 cm (12+1⁄2–15+1⁄2 in) from head to tail, with a wingspan of 65–82 cm (25+1⁄2–32+1⁄2 in). The female is noticeably larger, with the adult male weighing 136–252 g (4+3⁄4–8+7⁄8 oz), around 155 g (5+1⁄2 oz) on average; the adult female weighs 154–314 g (5+3⁄8–11+1⁄8 oz), around 184 g (6+1⁄2 oz) on average. They are thus small compared with other birds of prey, but larger than most songbirds. Like the other Falco species, they have long wings as well as a distinctive long tail.[4] The plumage is mainly light chestnut brown with blackish spots on the upperside and buff with narrow blackish streaks on the underside; the remiges are also blackish. Unlike most raptors, they display sexual colour dimorphism with the male having fewer black spots and streaks, as well as a blue-grey cap and tail. The tail is brown with black bars in females, and has a black tip with a narrow white rim in both sexes. All common kestrels have a prominent black malar stripe like their closest relatives.[4] The cere, feet, and a narrow ring around the eye are bright yellow; the toenails, bill and iris are dark. Juveniles look like adult females, but the underside streaks are wider; the yellow of their bare parts is paler. Hatchlings are covered in white down feathers, changing to a buff-grey second down coat before they grow their first true plumage.[4] Behaviour and ecologyIn the cool-temperate parts of its range, the common kestrel migrates south in winter; otherwise it is sedentary, though juveniles may wander around in search for a good place to settle down as they become mature. It is a diurnal animal of the lowlands and prefers open habitat such as fields, heaths, shrubland and marshland. It does not require woodland to be present as long as there are alternative perching and nesting sites like rocks or buildings. It will thrive in treeless steppe where there are abundant herbaceous plants and shrubs to support a population of prey animals. The common kestrel readily adapts to human settlement, as long as sufficient swathes of vegetation are available, and may even be found in wetlands, moorlands and arid savanna. It is found from the sea to the lower mountain ranges, reaching elevations up to 4,500 m (14,800 ft) ASL in the hottest tropical parts of its range but only to about 1,750 m (5,740 ft) in the subtropical climate of the Himalayan foothills.[4][24] Globally, this species is not considered threatened by the IUCN.[1] Its stocks were affected by the indiscriminate use of organochlorines and other pesticides in the mid-20th century, but being something of an r-strategist able to multiply quickly under good conditions it was less affected than other birds of prey. The global population has been fluctuating considerably over the years but remains generally stable; it is roughly estimated at 1–2 million pairs or so, about 20% of which are found in Europe. There has been a recent decline in parts of Western Europe such as Ireland. Subspecies dacotiae is quite rare, numbering less than 1000 adult birds in 1990, when the ancient western Canarian subspecies canariensis numbered about ten times as many birds.[4] Food and feeding  When hunting, the common kestrel characteristically hovers about 10–20 m (35–65 ft) above the ground, searching for prey, either by flying into the wind or by soaring using ridge lift. Like most birds of prey, common kestrels have keen eyesight enabling them to spot small prey from a distance. Once prey is sighted, the bird makes a short, steep dive toward the target, unlike the peregrine which relies on longer, higher dives to reach full speed when targeting prey. Kestrels can often be found hunting along the sides of roads and motorways, where the road verges support large numbers of prey. This species is able to see near ultraviolet light, allowing the birds to detect the urine trails around rodent burrows as they shine in an ultraviolet colour in the sunlight.[25] Another favourite (but less conspicuous) hunting technique is to perch a bit above the ground cover, surveying the area. When the bird spots prey animals moving by, it will pounce on them. They also prowl a patch of hunting ground in a ground-hugging flight, ambushing prey as they happen across it.[4]  They eat almost exclusively mouse-sized mammals. Voles, shrews and true mice supply up to three-quarters or more of the biomass most individuals ingest. On oceanic islands (where mammals are often scarce), small birds (mainly passerines) may make up the bulk of its diet.[6] Elsewhere, birds are only an important food during a few weeks each summer when inexperienced fledglings abound. Other suitably sized vertebrates like bats, swifts,[26] frogs[citation needed] and lizards are eaten only on rare occasions. However, kestrels are more likely to prey on lizards in southern latitudes. In northern latitudes, the kestrel is found more often to deliver lizards to their nestlings during midday and also with increasing ambient temperature.[27] Seasonally, arthropods may be a main prey item. Generally, invertebrates like camel spiders and even earthworms, but mainly sizeable insects such as beetles, orthopterans and winged termites will be eaten.[4] The common kestrel requires the equivalent of 4–8 voles a day, depending on energy expenditure (time of the year, amount of hovering, etc.). They have been known to catch several voles in succession and cache some for later consumption. An individual nestling consumes on average 4.2 g/h, equivalent to 67.8 g/d (3–4 voles per day).[28] Breeding  The common kestrel starts breeding in spring (or the start of the dry season in the tropics), i.e. April or May in temperate Eurasia and some time between August and December in the tropics and southern Africa. It is a cavity nester, preferring holes in cliffs, trees or buildings; in built-up areas, common kestrels will often nest on buildings, and will reuse the old nests of corvids. The diminutive subspecies dacotiae, the sarnicolo of the eastern Canary Islands is peculiar for nesting occasionally in the dried fronds below the top of palm trees, apparently coexisting with small songbirds which also make their home there.[29] In general, common kestrels will usually tolerate conspecifics nesting nearby, and sometimes a few dozen pairs may be found nesting in a loose colony.[4] The clutch is normally 3–7 eggs; more eggs may be laid in total but some will be removed during the laying time. This lasts about 2 days per egg laid. The eggs are abundantly patterned with brown spots, from a wash that tinges the entire surface buffish white to large almost-black blotches. Incubation lasts from 4 weeks to one month, both male and female will take shifts incubating the eggs. After the eggs have hatched, the parents share brooding and hunting duties. Only the female feeds the chicks, by tearing apart prey into manageable chunks. The young fledge after 4–5 weeks. The family stays close together for a few weeks, during which time the young learn how to fend for themselves and hunt prey. The young become sexually mature the next breeding season.[4] Female kestrel chicks with blacker plumage have been found to have bolder personalities, indicating that even in juvenile birds plumage coloration can act as a status signal.[30] Data from Britain shows nesting pairs bringing up about 2–3 chicks on average, though this includes a considerable rate of total brood failures; actually, few pairs that do manage to fledge offspring raise less than 3 or 4. Compared to their siblings, first-hatched chicks have greater survival and recruitment probability, thought to be due to the first-hatched chicks obtaining a higher body condition when in the nest.[31] Population cycles of prey, particularly voles, have a considerable influence on breeding success. Most common kestrels die before they reach 2 years of age; mortality up until the first birthday may be as high as 70%. At least females generally breed at one year of age;[32] possibly, some males take a year longer to maturity as they do in related species. The biological lifespan to death from senescence can be 16 years or more, however; one was recorded to have lived almost 24 years.[32]

In culture The kestrel is sometimes seen, like other birds of prey, as a symbol of the power and vitality of nature. In "Into Battle" (1915), the war poet Julian Grenfell invokes the superhuman characteristics of the kestrel among several birds, when hoping for prowess in battle:

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889) writes on the kestrel in his poem "The Windhover", exalting in their mastery of flight and their majesty in the sky.

A kestrel is also one of the main characters in The Animals of Farthing Wood. Barry Hines' novel A Kestrel for a Knave - together with the 1969 film based on it, Ken Loach's Kes - is about a working-class boy in England who befriends a kestrel. The Pathan name for the kestrel, Bād Khurak, means "wind hover" and in Punjab it is called Larzānak or "little hoverer". It was once used as a decoy to capture other birds of prey in Persia and Arabia. It was also used to train greyhounds meant for hunting gazelles in parts of Arabia. Young greyhounds would be set after jerboa-rats which would also be distracted and forced to make twists and turns by the dives of a kestrel.[33] References

Sources

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Falco tinnunculus. Wikispecies has information related to Falco tinnunculus. Common kestrel media from ARKive

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||