Black Rednecks and White Liberals

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Dalam nama Tionghoa ini, nama keluarganya adalah Cui. Cui JianCui Jian dalam Festival Rock Hohaiyan di Taiwan, 2007Lahir2 Agustus 1961 (umur 62)Beijing, TiongkokPekerjaanPenyanyi, penulis lagu, musisiTahun aktif1984–kiniKarier musikNama lainOld Cui (Hanzi: 老崔; Pinyin: Lǎo Cuī)AsalTiongkokGenreRock, punk rock, rap rock, electropunkInstrumenVokal, gitar, gitar listrik, terompetLabelBeijing East-WestSitus webwww.cuijian.com Cui JianJosŏn-gŭl최건 Hanja崔健 Alih Aks...

Gajahan Gajahan besar (Numenius arcuata)lukisan artis Jerman tahun 1902 Klasifikasi ilmiah Kerajaan: Animalia Filum: Chordata Kelas: Aves Ordo: Charadriiformes Famili: Scolopacidae Genus: NumeniusBrisson, 1760 Spesies tipe Scolopax arquataLinnaeus, 1758 Spesies N. americanus N. arquata N. borealis N. madagascariensis N. minutus N. phaeopus N. tahitiensis N. tenuirostris Sinonim Palnumenius Miller, 1942 Gajahan adalah nama umum bagi burung perandai anggota genus Numenius, suku Scolopacidae. T...

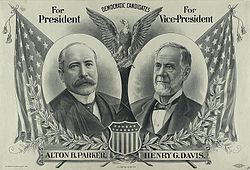

American judge (1852–1926) Alton B. ParkerParker in 1906Chief Judge of the New York Court of AppealsIn officeJanuary 1, 1898 – August 5, 1904Preceded byCharles AndrewsSucceeded byEdgar M. Cullen Personal detailsBornAlton Brooks Parker(1852-05-14)May 14, 1852Cortland, New York, U.S.DiedMay 10, 1926(1926-05-10) (aged 73)New York City, New York, U.S.Resting placeWiltwyck CemeteryPolitical partyDemocraticSpouse(s)Mary SchoonmakerAmy Day CampbellEducationAlbany Law School (LLB) A...

City in Razavi Khorasan province, Iran For other places with the same name, see Bidokht. City in Razavi Khorasan, IranBidokht Persian: بيدختCityBidokhtCoordinates: 34°20′52″N 58°45′23″E / 34.34778°N 58.75639°E / 34.34778; 58.75639[1]CountryIranProvinceRazavi KhorasanCountyGonabadDistrictCentralPopulation (2016)[2] • Total5,501Time zoneUTC+3:30 (IRST)Bidokht at GEOnet Names Server Bidokht (Persian: بيدخت, also Roman...

Henry CavillCavill pada tahun 2011LahirHenry William Dalgliesh Cavill5 Mei 1983 (umur 40)Jersey, Kepulauan ChannelKebangsaanBritania RayaPekerjaanAktorTahun aktif2001–sekarang Henry William Dalgliesh Cavill (/ˈkævəl/; lahir 5 Mei 1983) adalah aktor Inggris. Ia dikenal karena perannya sebagai Charles Brandon di Showtime The Tudors (2007–2010), DC Comics character Superman dalam DC Extended Universe, Geralt of Rivia dalam Netflix seri fantasi The Witcher (2019–sekarang), dan...

Tributary river in Eritrea Anseba Shet'LocationCountryEritreaPhysical characteristicsSource • locationEritrean Highlands Mouth • locationinto Barka River near Per TokarLength346 km (215 mi)Basin size12,100 km2 (4,700 sq mi)[1]Basin featuresRiver systemBarka River The Anseba River (Tigrinya: ሩባ ዓንሰባ, Arabic: نهر أنسيبا) is a tributary of the Barka River in Eritrea with a length of 346 ki...

Dieser Artikel behandelt die Schauspielerin und Sängerin; für den Film Lída Baarová von Filip Renč (2016) siehe Die Geliebte des Teufels. Lída Baarová (1940) Lída Baarová (* 7. September 1914 als Ludmila Babková in Prag, Österreich-Ungarn; † 27. Oktober 2000 in Salzburg) war eine tschechische Schauspielerin und Sängerin. Durch ihre Nähe zur nationalsozialistischen Elite, insbesondere jedoch ihre Affäre mit Joseph Goebbels, war sie zeitlebens umstritten. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 L...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (يناير 2022) هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالات أخرى قليلة جدًا. فضلًا، ساعد بإضافة وصلة إليها في مقالات متعلقة بها. ...

Annual pre-Easter Christian observance This article is about the general Christian pre-Easter period. For Lent in Eastern Christianity, see Great Lent. For other uses, see Lent (disambiguation). LentQuadragesimaHigh altar, barren, with few adornments, as is custom during LentTypeChristianCelebrations Omission of Gloria and Alleluia Veiling of religious images ObservancesFastingPrayingAlms givingAbstinenceBeginsOn Ash Wednesday (Western)On Clean Monday (Eastern)EndsOn Holy Thursday (Latin Cath...

Gabriel Zamora is a municipality in the center of the Mexican square kilometres (0.72% of the surface of the state)[1] and is bordered to the north by the municipalities of Nuevo Parangaricutiro, Uruapan and Taretan, to the east by Nuevo Urecho, to the south by Múgica, and to the west by Parácuaro. The municipality had a population of 19,876 inhabitants according to the 2005 census.[2] Its municipal seat is the city of Lombardía. Before having its name change to Gabriel Zam...

Australian engineer and inventor (1850–1915) Lawrence HargraveMRAeSLawrence Hargrave, c. 1890Born(1850-01-29)29 January 1850Greenwich, EnglandDied6 July 1915(1915-07-06) (aged 65)NationalityAustralian Lawrence Hargrave, MRAeS,[1] (29 January 1850 – 6 July 1915)[nb 1] was an Australian engineer, explorer, astronomer, inventor and aeronautical pioneer. Biography Lawrence Hargrave was born in Greenwich, England, the second son of John Fletcher Hargrave ...

Петлица высшего классного чина Главного государственного советника налоговой службы Главный государственный советник налоговой службы — высший классный чин в налоговых органах Российской Федерации в 1991—2001 гг. (ниже — государственный советник налоговой служ...

Stone cross set up where a murder or accident happened Conciliation cross near Jaroměř, the largest in the Czech Republic Conciliation cross, also known as roadside cross or penitence cross, is a stone cross, which was set up in a place where a murder or accident had happened. It occurs mainly in Central Europe. Purpose In the Middle Ages and in the early modern period, the conciliation crosses were erected as a symbol of penance for crime, most often for murder. If the perpetrator of the m...

本模板依照頁面品質評定標準无需评级。本Template属于下列维基专题范畴: 天文专题 (获评模板級、不适用重要度) 天文WikiProject:天文Template:WikiProject Astronomy天文条目 天文学主题查论编本Template属于天文专题范畴,该专题旨在改善中文维基百科天文学相关条目类内容。如果您有意参与,请浏览专题主页、参与讨论,并完成相应的开放性任务。 模板 根据专...

University of MacerataUniversità degli Studi di MacerataTypePublicEstablished1290RectorJohn Francis Mc CourtStudents11,213 (2008)[1]LocationMacerata, ItalySports teamsCus MacerataAffiliationsMacerata Student NetworkWebsitewww.unimc.it The grand hall of the University The University of Macerata (Italian: Università degli Studi di Macerata) is a public university located in Macerata, Italy. It is one of the oldest universities in Europe that are still functioning.[2] Overview...

1973 1981 Élections législatives de 1978 dans la Manche 5 sièges de députés à l'Assemblée nationale 12 et 19 mars 1978 Corps électoral et résultats Inscrits 316 210 Votants au 1er tour 264 315 83,59 % 2,1 Votes exprimés au 1er tour 260 096 Votants au 2d tour 261 626 82,76 % Votes exprimés au 2d tour 250 279 Majorité présidentielle Liste Rassemblement pour la RépubliqueUnion pour la démocratie françaiseDivers droite Vo...

フレンチ・キスの楽曲については「思い出せない花」をご覧ください。 2024年 6月(水無月) 日 月 火 水 木 金 土 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 日付の一覧 各月 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 6月29日(ろくがつにじゅうくにち)は、グレゴリオ暦で年始から180日目(閏年では181日目)にあたり、年末まであと185日ある。 できごと 長篠の戦い(1575)、織...

Politics of Kiribati Constitution Human rights LGBT rights Executive President Taneti Maamau Vice-President Teuea Toatu Cabinet Legislative House of Assembly Speaker: Tangariki Reete Members Judiciary Court of Appeal President: Sir Peter Blanchard High Court Chief Justice: Bill Hastings (suspended) Elections Recent elections Presidential: 20162020 Parliamentary: 2015–162020 Political parties Subdivisions Foreign relations Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Immigration Minister: Taneti Maamau ...

تجمع الخفسة - قرية - تقسيم إداري البلد اليمن المحافظة محافظة حضرموت المديرية مديرية العبر العزلة عزلة العبر السكان التعداد السكاني 2004 السكان 27 • الذكور 14 • الإناث 13 • عدد الأسر 4 • عدد المساكن 4 معلومات أخرى التوقيت توقيت اليمن (+3 غرينيتش) تعد�...

This article is about the German People's Party which existed between 1918 and 1933. For other parties with same name, see German People's Party (disambiguation). Political party in Germany German People's Party Deutsche VolksparteiLeaderGustav StresemannFounded15 December 1918; 105 years ago (15 December 1918)Dissolved4 July 1933; 91 years ago (4 July 1933)Preceded byNational Liberal PartyFree Conservative Party (moderate elements)Merged intoFree Democ...