| Name

|

Year

|

Formation

|

Location

|

Notes

|

Images

|

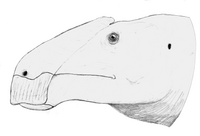

| Abydosaurus

|

2010

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Had a short domed crest on its skull similar to that of Giraffatitan

|

![]()

|

| Acantholipan

|

2018

|

Pen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian)

|

Mexico Mexico

( Coahuila) Coahuila)

|

Known to possess spike-like osteoderms

|

|

| Achelousaurus

|

1994

|

Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Combines long spikes on the top of its frill and a low keratinous boss over its eyes and nose

|

|

| Acheroraptor

|

2013

|

Hell Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

One of the geologically youngest dromaeosaurids

|

|

| Acristavus

|

2011

|

Two Medicine Formation, Wahweap Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana Montana

Utah) Utah)

|

Uniquely for a hadrosaurid, it lacked any ornamentation on its skull

|

|

| Acrocanthosaurus

|

1950

|

Antlers Formation, Arundel Formation, Cloverly Formation, Twin Mountains Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian)

|

United States United States

( Maryland Maryland

Oklahoma Oklahoma

Texas Texas

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Possessed elongated neural spines that would have supported a low sail or hump in life

|

|

| Acrotholus

|

2013

|

Milk River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Had a tall, oval-shaped dome

|

|

| Adelolophus

|

2014

|

Wahweap Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Potentially a close relative of Parasaurolophus[5]

|

|

| Agujaceratops

|

2006

|

Aguja Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

The type species was originally assigned to the genus Chasmosaurus

|

|

| Ahshislepelta

|

2011

|

Kirtland Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Relatively small compared to other North American ankylosaurs

|

|

| Akainacephalus

|

2018

|

Kaiparowits Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Much of the skeleton is known, including the entirety of the skull

|

|

| Alamosaurus

|

1922

|

Black Peaks Formation, El Picacho Formation, Evanston Formation?, Javelina Formation, North Horn Formation, Ojo Alamo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico New Mexico

Texas Texas

Utah Utah

Wyoming?) Wyoming?)

|

The only titanosaur confirmed to have crossed into North America. One of the largest dinosaurs known from the continent[6]

|

|

| Alaskacephale

|

2006

|

Prince Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Alaska) Alaska)

|

Had an array of polygonal nodes on its squamosal

|

|

| Albertaceratops

|

2007

|

Oldman Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Possessed long brow horns and a bony ridge over its nose

|

|

| Albertadromeus

|

2013

|

Oldman Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

The proportions of its hindlimb suggest a cursorial lifestyle

|

|

| Albertavenator

|

2017

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Its discovery suggests that the diversity of small dinosaurs may be higher than previously thought

|

|

| Albertonykus

|

2009

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

May have used its specialized forelimbs to dig into tree trunks for feeding on termites[7]

|

|

| Albertosaurus

|

1905

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Known from more than thirty specimens, twenty-six of which are preserved together[8]

|

|

| Aletopelta

|

2001

|

Point Loma Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( California) California)

|

Would have lived in present-day Mexico. Its fossils were only found in California due to the shifting of tectonic plates

|

|

| Allosaurus

|

1877

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

Oklahoma Oklahoma

Utah Utah

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Multiple specimens have been discovered, making it well-known both popularly and scientifically. At least three species are known from the United States, in addition to one described from Portugal

|

|

| Ampelognathus

|

2023

|

Lewisville Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

More closely related to iguanodonts than to the morphologically similar "hypsilophodonts"[9]

|

|

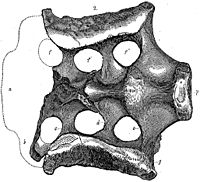

| Amphicoelias

|

1878

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado) Colorado)

|

Originally believed to date from the Cretaceous

|

|

| Anasazisaurus

|

1993

|

Kirtland Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

May have been a second species of Kritosaurus[10]

|

|

| Anchiceratops

|

1914

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Had a long, rectangular frill ringed by short, triangular spikes

|

|

| Anchisaurus

|

1885

|

Portland Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian to Sinemurian)

|

United States United States

( Connecticut Connecticut

Massachusetts) Massachusetts)

|

Some possible remains were originally misidentified as human skeletons[11]

|

|

| Angulomastacator

|

2009

|

Aguja Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

The tip of its jaw was angled 45° at its anterior end, with the tooth row bent to match

|

|

| Animantarx

|

1999

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous to Late Cretaceous, Albian to Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Its holotype was discovered during a radiological survey of a fossil site. No bones were exposed before it was excavated

|

|

| Ankylosaurus

|

1908

|

Ferris Formation, Frenchman Formation, Hell Creek Formation, Lance Formation, Scollard Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta Alberta

Saskatchewan) Saskatchewan)

United States United States

( Montana Montana

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

The largest and most well-known ankylosaur

|

|

| Anodontosaurus

|

1929

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Originally mistakenly believed to have been toothless

|

|

| Anzu

|

2014

|

Hell Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( Montana Montana

North Dakota North Dakota

South Dakota) South Dakota)

|

Large and known from considerably good remains. Preserves evidence of a tall head crest

|

|

| Apatoraptor

|

2016

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Quill knobs preserved on its ulna confirm this genus had wings

|

|

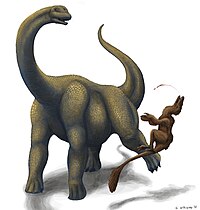

| Apatosaurus

|

1877

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

New Mexico New Mexico

Oklahoma Oklahoma

Utah Utah

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Had a characteristically robust skeleton compared to other diplodocids

|

|

| Appalachiosaurus

|

2005

|

Blufftown Formation?, Demopolis Chalk, Donoho Creek Formation?, Ripley Formation?, Tar Heel/Coachman Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Alabama Alabama

Georgia (U.S. state)? Georgia (U.S. state)?

North Carolina? North Carolina?

South Carolina?) South Carolina?)

|

The most complete theropod known from the eastern side of North America

|

|

| Aquilarhinus

|

2019

|

Aguja Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

May have been a semiaquatic, coastal species that used its unusual, shovel-shaped bill to scoop up vegetation in wet sediment[12]

|

|

| Aquilops

|

2014

|

Cloverly Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

May have had a short horn protruding from its upper beak

|

|

| Ardetosaurus

|

2024

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

The holotype specimen was damaged by a museum fire

|

|

| Arkansaurus

|

2018

|

Trinity Group (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian)

|

United States United States

( Arkansas) Arkansas)

|

State dinosaur of Arkansas. Its generic name was in use informally even before its formal description

|

|

| Arrhinoceratops

|

1925

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Described as lacking a nasal horn although this is an artifact of preservation

|

|

| Astrodon

|

1865

|

Antlers Formation?, Arundel Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian)

|

United States United States

( Maryland Maryland

Oklahoma?) Oklahoma?)

|

State dinosaur of Maryland

|

|

| Astrophocaudia

|

2012

|

Trinity Group (Early Cretaceous, Albian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

Known from a single partial skeleton

|

|

| Atlantosaurus

|

1877

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado) Colorado)

|

Potentially synonymous with Apatosaurus,[13] but a referred species may represent a separate taxon[14]

|

|

| Atrociraptor

|

2004

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Had a short, deep snout with enlarged teeth

|

|

| Aublysodon

|

1868

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Only known from teeth

|

|

| Augustynolophus

|

2014

|

Moreno Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( California) California)

|

State dinosaur of California. Originally named as a species of Saurolophus

|

|

| Avaceratops

|

1986

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Lacked the fenestrae in its frill, a feature shared only with Triceratops

|

|

| Bambiraptor

|

2000

|

Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Small but well-preserved enough to display its mix of dinosaur- and bird-like features

|

|

| Barosaurus

|

1890

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( South Dakota South Dakota

Utah) Utah)

|

Similar to Diplodocus but larger and with a longer neck

|

|

| Bistahieversor

|

2010

|

Fruitland Formation, Kirtland Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Analysis of its braincase suggests it behaved like tyrannosaurids despite likely not being a member of that family[15]

|

|

| Bisticeratops

|

2022

|

Kirtland Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Preserves bite marks from a tyrannosaurid

|

|

| Borealopelta

|

2017

|

Clearwater Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

So well-preserved that several osteoderms, keratin, pigments and stomach contents are preserved in the positions they would have been in while alive, without flattening or shriveling

|

|

| Boreonykus

|

2015

|

Wapiti Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

One of the few dromaeosaurids known from high latitudes

|

|

| Brachiosaurus

|

1903

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

Oklahoma Oklahoma

Utah Utah

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

A high browser with a tall chest and elongated forelimbs

|

|

| Brachyceratops

|

1914

|

Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Only known from juvenile remains. One specimen has been found to represent a subadult Styracosaurus ovatus

|

|

| Brachylophosaurus

|

1953

|

Judith River Formation, Oldman Formation, Wahweap Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana Montana

Utah?) Utah?)

|

Several specimens preserve extensive soft tissue remains

|

|

| Bravoceratops

|

2013

|

Javelina Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

Suggested to have had a single small horn on the top of its frill but this may be inaccurate

|

|

| Brontomerus

|

2011

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Possessed an enlarged ilium which supported powerful leg muscles, which it may have used to kick away predators

|

|

| Brontosaurus

|

1879

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Utah Utah

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Popularly associated with Apatosaurus but a 2015 study found enough differences for it to be classified as a separate genus[14]

|

|

| Caenagnathus

|

1940

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

One of the largest known caenagnathids[16]

|

|

| Camarasaurus

|

1877

|

Morrison Formation, Summerville Formation? (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

New Mexico? New Mexico?

Oklahoma? Oklahoma?

South Dakota? South Dakota?

Utah Utah

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Very common and known from multiple specimens

|

|

| Camposaurus

|

1998

|

Bluewater Creek Formation (Late Triassic, Norian)

|

United States United States

( Arizona) Arizona)

|

Potentially the oldest known neotheropod

|

|

| Camptosaurus

|

1885

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Utah Utah

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

May have fed on tough vegetation as evidenced by extensive wear frequently exhibited on its teeth[17]

|

|

| Caseosaurus

|

1998

|

Tecovas Formation (Late Triassic, Norian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

Possibly synonymous with Chindesaurus

|

|

| Cedarosaurus

|

1999

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

One specimen preserves over a hundred gastroliths[18]

|

|

| Cedarpelta

|

2001

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Lacked the extensive cranial ornamentation of later ankylosaurids

|

|

| Cedrorestes

|

2007

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Known from a partial skeleton. The specific name, crichtoni, honors Michael Crichton, author of Jurassic Park and The Lost World

|

|

| Centrosaurus

|

1904

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Hundreds of individuals have been preserved in a single "mega-bonebed"[19]

|

|

| Cerasinops

|

2007

|

Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Combines features of both Asian and North American basal ceratopsians

|

|

| Ceratops

|

1888

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Although only known from a few bones, this genus is the namesake of the Ceratopsia and the Ceratopsidae

|

|

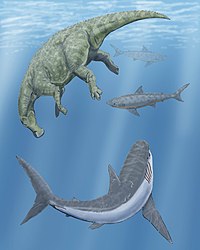

| Ceratosaurus

|

1884

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

Utah Utah

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Possessed a row of osteoderms running down its back

|

|

| Chasmosaurus

|

1914

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Known from multiple remains, including various skulls

|

|

| Chindesaurus

|

1995

|

Chinle Formation (Late Triassic, Norian)

|

United States United States

( Arizona) Arizona)

|

May be a herrerasaur or a close relative of Tawa[20]

|

|

| Chirostenotes

|

1924

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Originally known only from isolated body parts

|

|

| Cionodon

|

1874

|

Denver Formation, Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Colorado) Colorado)

|

Poorly known

|

|

| Citipes

|

2020

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Some specimens were found as stomach contents of Gorgosaurus[21]

|

|

| Claosaurus

|

1890

|

Niobrara Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian to Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Kansas) Kansas)

|

Historically conflated with other hadrosaurs

|

|

| Coahuilaceratops

|

2010

|

Cerro Huerta Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Mexico Mexico

( Coahuila) Coahuila)

|

Possessed brow horns comparable in size to those of Triceratops and Torosaurus

|

|

| Coahuilasaurus

|

2024

|

Cerro del Pueblo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Mexico Mexico

( Coahuila) Coahuila)

|

Identified as a specimen of Kritosaurus[22] before receiving its own genus name[23]

|

|

| Coelophysis

|

1889

|

Chinle Formation (Late Triassic, Norian)

|

United States United States

( Arizona Arizona

New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Known from over a thousand specimens, making it one of the most well-known early dinosaurs. Some referred species may belong to their own genera

|

|

| Coelurus

|

1879

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Potentially an early member of the tyrannosauroid lineage[24]

|

|

| Colepiocephale

|

2003

|

Foremost Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Originally described as a species of Stegoceras

|

|

| Convolosaurus

|

2019

|

Twin Mountains Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

Before its formal description, it had been informally referred to as the "Proctor Lake hypsilophodontid"

|

|

| Coronosaurus

|

2012

|

Oldman Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Had irregular masses of small spikes on the very top of its frill

|

|

| Corythosaurus

|

1914

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Oldman Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Possessed a semicircular crest which may have been used for vocalization

|

|

| Crittendenceratops

|

2018

|

Fort Crittenden Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Arizona) Arizona)

|

The youngest known member of the Nasutoceratopsini

|

|

| Daemonosaurus

|

2011

|

Chinle Formation (Late Triassic, Norian to Rhaetian?)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Unique among early dinosaurs for possessing a short snout with long teeth

|

|

| Dakotadon

|

2008

|

Lakota Formation (Early Cretaceous, Barremian)

|

United States United States

( South Dakota) South Dakota)

|

Originally named as a species of Iguanodon

|

|

| Dakotaraptor

|

2015

|

Hell Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( South Dakota) South Dakota)

|

The holotype assemblage may represent a chimera of multiple taxa[25]

|

|

| Daspletosaurus

|

1970

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Judith River Formation, Oldman Formation, Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

At least three species are known. These have been interpreted as forming an anagenetic lineage[26] but this hypothesis has been criticized[27]

|

|

| Deinonychus

|

1969

|

Antlers Formation, Arundel Formation?, Cedar Mountain Formation?, Cloverly Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian)

|

United States United States

( Maryland? Maryland?

Montana Montana

Oklahoma Oklahoma

Utah? Utah?

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Its discovery helped researchers realize that dinosaurs were active, warm-blooded animals, kicking off the Dinosaur Renaissance

|

|

| Denversaurus

|

1988

|

Lance Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( South Dakota South Dakota

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

The youngest known nodosaurid[28]

|

|

| Diabloceratops

|

2010

|

Wahweap Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Had a distinctively short, deep skull

|

|

| Diclonius

|

1876

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Replaced its teeth in such a way that new teeth could be used at the same time as older ones

|

|

| Dilophosaurus

|

1970

|

Kayenta Formation (Early Jurassic, Sinemurian to Toarcian)

|

United States United States

( Arizona) Arizona)

|

Possessed two semicircular crests running along the length of the skull

|

|

| Dineobellator

|

2020

|

Ojo Alamo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Several features of its hands and feet may be adaptations for increased grip strength[29]

|

|

| Diplodocus

|

1878

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian?)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

Montana Montana

New Mexico New Mexico

Utah Utah

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Had a long, thin tail. Popularly thought to have been used like a bullwhip[30] but it is possible that it could not handle the stress of supersonic travel[31]

|

|

| Diplotomodon

|

1868

|

Hornerstown Formation?/Navesink Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( New Jersey) New Jersey)

|

Has been suggested to be non-dinosaurian

|

|

| Dromaeosaurus

|

1922

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Hell Creek Formation?, Horseshoe Canyon Formation?, Prince Creek Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian?)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Alaska? Alaska?

South Dakota?) South Dakota?)

|

Analysis of wear on its teeth suggests it preferred tougher prey, including bone

|

|

| Dromiceiomimus

|

1972

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

May be synonymous with Ornithomimus edmontonicus

|

|

| Dryosaurus

|

1894

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

Utah Utah

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Remains of multiple growth stages have been found, including specimens in embryonic age[32]

|

|

| Dryptosaurus

|

1877

|

Navesink Formation?, New Egypt Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( New Jersey) New Jersey)

|

Its discovery showed that theropods were bipedal animals

|

|

| Dynamoterror

|

2018

|

Menefee Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Part of the Teratophoneini, a clade of tyrannosaurids exclusively known from southwestern North America[27]

|

|

| Dyoplosaurus

|

1924

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

The holotype specimen preserves skin impressions[33]

|

|

| Dysganus

|

1876

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Four species have been named, all from isolated teeth

|

|

| Dyslocosaurus

|

1992

|

Lance Formation?/Morrison Formation? (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian?/Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian?)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Has been suggested to have four claws on its hindlimbs

|

|

| Dystrophaeus

|

1877

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Oxfordian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Inconsistent in phylogenetic placement, although undescribed remains could further clarify its relationships

|

|

| Edmontonia

|

1928

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Horseshoe Canyon Formation, Judith River Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana?) Montana?)

|

Possessed forward-pointing, bifurcated spikes on its shoulders

|

|

| Edmontosaurus

|

1917

|

Frenchman Formation, Hell Creek Formation, Horseshoe Canyon Formation, Lance Formation, Prince Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta Alberta

Saskatchewan) Saskatchewan)

United States United States

( Alaska Alaska

Colorado Colorado

Montana Montana

North Dakota North Dakota

South Dakota South Dakota

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Known from multiple well-preserved specimens, including a few "mummies". Several were originally assigned to their own genera and/or species

|

|

| Einiosaurus

|

1994

|

Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Distinguished by its forward-curving nasal horn

|

|

| Eolambia

|

1998

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Remains of multiple individuals are known, making up much of the skeleton

|

|

| Eoneophron

|

2024

|

Hell Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( South Dakota) South Dakota)

|

Smaller than the contemporary Anzu

|

|

| Eotrachodon

|

2016

|

Mooreville Chalk (Late Cretaceous, Santonian)

|

United States United States

( Alabama) Alabama)

|

Had a saurolophine-like skull despite its basal position[34]

|

|

| Eotriceratops

|

2007

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

May have been the largest known ceratopsid

|

|

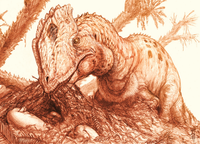

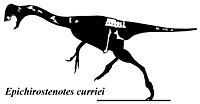

| Epichirostenotes

|

2011

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Its discovery allowed researchers to connect isolated caenagnathid body parts to each other

|

|

| Euoplocephalus

|

1910

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Unusually, its palpebral bone was mobile, allowing it to be used as an eyelid[35]

|

|

| Falcarius

|

2005

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Transitional between generalized theropods and specialized therizinosaurs

|

|

| Ferrisaurus

|

2019

|

Tango Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( British Columbia) British Columbia)

|

Its holotype was discovered close to a railway line[36]

|

|

| Fona

|

2024

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Possibly a semi-fossorial animal based on the related Oryctodromeus[37]

|

|

| Foraminacephale

|

2016

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Oldman Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Originally assigned to three different pachycephalosaurid genera

|

|

| Fosterovenator

|

2014

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Has been variously described as a ceratosaurid, a tetanuran or a close relative of Elaphrosaurus[38]

|

|

| Fruitadens

|

2010

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado) Colorado)

|

One of the smallest known ornithischians[39]

|

|

| Furcatoceratops

|

2023

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Preserves most of the postcranial skeleton, a rarity for ceratopsids. Remains originally identified as Avaceratops

|

|

| Galeamopus

|

2015

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

One specimen is nearly complete, even preserving an associated skull

|

|

| Gargoyleosaurus

|

1998

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Combines features of both ankylosaurids and nodosaurids

|

|

| Gastonia

|

1998

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Several concentrations of fossils may suggest this taxon lived in herds[40]

|

|

| Geminiraptor

|

2010

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

The proportions of its maxilla are similar to those of Late Cretaceous troodontids

|

|

| Glishades

|

2010

|

Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana Montana

|

Described as a basal hadrosauroid but may in fact be a juvenile saurolophine hadrosaurid[41]

|

|

| Glyptodontopelta

|

2000

|

Ojo Alamo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Originally interpreted as possessing a flat mosaic of osteoderms similar to the shields of glyptodonts

|

|

| Gojirasaurus

|

1997

|

Bull Canyon Formation (Late Triassic, Norian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

May be a chimera consisting of undiagnostic theropod bones mixed with pseudosuchian vertebrae[42]

|

|

| Gorgosaurus

|

1914

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Judith River Formation?, Two Medicine Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana?) Montana?)

|

Dozens of specimens are known

|

|

| Gravitholus

|

1979

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Potentially synonymous with Stegoceras[43]

|

|

| Gremlin

|

2023

|

Oldman Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Possessed a ridge running along the top of the skull

|

|

| Gryphoceratops

|

2012

|

Milk River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Potentially the smallest adult ceratopsian known from North America

|

|

| Gryposaurus

|

1914

|

Bearpaw Formation?, Dinosaur Park Formation, Javelina Formation?, Kaiparowits Formation, Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian to Maastrichtian?)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana Montana

Texas? Texas?

Utah) Utah)

|

One specimen preserves impressions of a row of pyramidal scales running along its back[44]

|

|

| Hadrosaurus

|

1858

|

Woodbury Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Jersey) New Jersey)

|

Its holotype was the first dinosaur skeleton to be mounted

|

|

| Hagryphus

|

2005

|

Kaiparowits Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Large but only known from a single hand

|

|

| Hanssuesia

|

2003

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Judith River Formation, Oldman Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

One dome preserves several lesions

|

|

| Haplocanthosaurus

|

1903

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

Montana? Montana?

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

One of the smallest sauropods of the Morrison Formation

|

|

| Hesperonychus

|

2009

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Oldman Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

A common component of its habitat as indicated by the great number of its remains

|

|

| Hesperornithoides

|

2019

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Oxfordian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Before its formal description, it had been nicknamed "Lori"

|

|

| Hesperosaurus

|

2001

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Montana Montana

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Two morphotypes of plates are known, which has been interpreted as an indication of sexual dimorphism[45]

|

|

| Hierosaurus

|

1909

|

Niobrara Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian to Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Kansas) Kansas)

|

Only known from a few bones, including osteoderms

|

|

| Hippodraco

|

2010

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Its tooth crowns were shaped like shields

|

|

| Hoplitosaurus

|

1902

|

Lakota Formation (Early Cretaceous, Barremian?)

|

United States United States

( South Dakota) South Dakota)

|

Known from some osteoderms, including spikes similar to those of Polacanthus

|

|

| Huehuecanauhtlus

|

2012

|

Unnamed formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian)

|

Mexico Mexico

( Michoacán) Michoacán)

|

The southernmost non-hadrosaurid hadrosauroid known from North America[46]

|

|

| Hypacrosaurus

|

1913

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation, Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Some juveniles of this genus were originally interpreted as dwarf lambeosaurines

|

|

| Hypsibema

|

1869

|

Marshalltown Formation?, Ripley Formation, Tar Heel/Coachman Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Missouri Missouri

New Jersey? New Jersey?

North Carolina) North Carolina)

|

Potentially one of the largest non-hadrosaurid hadrosauroids

|

|

| Hypsirhophus

|

1878

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado) Colorado)

|

Usually seen as synonymous with Stegosaurus but may be a separate genus due to differences in its vertebrae[47]

|

|

| Iani

|

2023

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Represents the family Tenontosauridae, a North American clade of rhabdodontomorphs[48]

|

|

| Iguanacolossus

|

2010

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Large and robustly built

|

|

| Invictarx

|

2018

|

Menefee Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Only known from a few bones but can be distinguished from other genera by characters of its osteoderms

|

|

| Issi

|

2021

|

Fleming Fjord Formation (Late Triassic, Norian)

|

Greenland Greenland

(Sermersooq)

|

Originally described as an exemplar of Plateosaurus

|

|

| Jeyawati

|

2010

|

Moreno Hill Formation (Late Cretaceous, Turonian to Coniacian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Its postorbital bone had a rugose texture

|

|

| Judiceratops

|

2013

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Unusually, its brow horns were teardrop-shaped in cross-section

|

|

| Kaatedocus

|

2012

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Originally interpreted as a diplodocid although one study finds it to be more likely a basal dicraeosaurid[49]

|

|

| Kayentavenator

|

2010

|

Kayenta Formation (Early Jurassic, Sinemurian to Pliensbachian)

|

United States United States

( Arizona) Arizona)

|

Described in a book published through an online print-on-demand service

|

|

| Koparion

|

1994

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Known from a single tooth which may have come from a troodontid

|

|

| Kosmoceratops

|

2010

|

Kaiparowits Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Possessed fifteen horns and horn-like structures, including eight hornlets folding down from the top of the frill

|

|

| Kritosaurus

|

1910

|

El Picacho Formation?, Javelina Formation?, Kirtland Formation, Ojo Alamo Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian?)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico New Mexico

Texas?) Texas?)

|

Had an elevated nasal bone with an enlarged nasal cavity to match

|

|

| Labocania

|

1974

|

Cerro del Pueblo Formation, La Bocana Roja Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian? to Campanian)

|

Mexico Mexico

( Baja California Baja California

Coahuila) Coahuila)

|

The description of the second species, L. aguillonae, suggests a position within the tyrannosaurid clade Teratophoneini[50]

|

|

| Lambeosaurus

|

1923

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Possessed a hollow head crest that varied in shape between species, sexes and ages. Most familiarly, it was hatchet-shaped in adult male L. lambei

|

|

| Laosaurus

|

1878

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Oxfordian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Several referred specimens have been reassigned to other taxa

|

|

| Latirhinus

|

2012

|

Cerro del Pueblo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Mexico Mexico

( Coahuila) Coahuila)

|

As described, it represented a chimera composed of lambeosaurine and saurolophine remains.[51] The exact holotypic bones belonged to a lambeosaurine[52]

|

|

| Lepidus

|

2015

|

Colorado City Formation (Late Triassic, Norian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

Muscle scars are preserved on the holotype bones

|

|

| Leptoceratops

|

1914

|

Hell Creek Formation, Lance Formation, Scollard Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana Montana

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Analysis of its teeth shows it could chew like a mammal, an adaptation to eating tough, fibrous plants[53]

|

|

| Leptorhynchos

|

2013

|

Aguja Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

Had a slightly upturned mandible similar to those of oviraptorids

|

|

| Lokiceratops

|

2024

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Unusually for a ceratopsid, its frill ornamentations were bilaterally asymmetrical. Closely related to Albertaceratops and Medusaceratops[54]

|

|

| Lophorhothon

|

1960

|

Mooreville Chalk, Tar Heel/Coachman Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Alabama Alabama

North Carolina?) North Carolina?)

|

Although incomplete, the holotype skull preserves evidence of a crest

|

|

| Lythronax

|

2013

|

Wahweap Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Already had the forward-directed orbits of derived tyrannosaurids despite its early age

|

|

| Machairoceratops

|

2016

|

Wahweap Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Possessed two long, forward-pointing horns on the top of its frill

|

|

| Magnapaulia

|

2012

|

El Gallo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Mexico Mexico

( Baja California) Baja California)

|

Has been suggested to be semi-aquatic due to its tall, narrow tail[55]

|

|

| Maiasaura

|

1979

|

Oldman Formation, Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Remains of hundreds of individuals, including juveniles, eggs and nests, have been found at a single site[56]

|

|

| Malefica

|

2022

|

Aguja Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

Its discovery suggests a greater diversity of basal hadrosaurids than previously thought

|

|

| Maraapunisaurus

|

2018

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado) Colorado)

|

Named from a single, lost vertebra of immense size

|

|

| Marshosaurus

|

1976

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado? Colorado?

Utah) Utah)

|

Potentially a close relative of Piatnitzkysaurus and Condorraptor[57]

|

|

| Martharaptor

|

2012

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Had not yet acquired the robust feet of derived therizinosaurs

|

|

| Medusaceratops

|

2010

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Possessed elongated spikes curving away from the sides of its frill

|

|

| Menefeeceratops

|

2021

|

Menefee Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

One of the oldest centrosaurines

|

|

| Mercuriceratops

|

2014

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Had "wing"-like projections on its squamosal bones

|

|

| Microvenator

|

1970

|

Cloverly Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Teeth from Deinonychus have been mistakenly attributed to this genus

|

|

| Mierasaurus

|

2017

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

One of the latest-surviving turiasaurs[58]

|

|

| Moabosaurus

|

2017

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Described as a macronarian[59] but has since been reinterpreted as a turiasaur closely related to Mierasaurus[58]

|

|

| Monoclonius

|

1876

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Only known from indistinct remains of juveniles and subadults

|

|

| Montanoceratops

|

1951

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation?, St. Mary River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Often restored with a short nasal horn although this may be a misplaced cheek horn[60]

|

|

| Moros

|

2019

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

The proportions of its metatarsals are similar to those of ornithomimids

|

|

| Mymoorapelta

|

1994

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

Utah) Utah)

|

The first ankylosaur described from the Morrison Formation

|

|

| Naashoibitosaurus

|

1993

|

Kirtland Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Like other kritosaurins, it possessed a nasal arch, but it was not as tall as that of Gryposaurus

|

|

| Nanosaurus

|

1877

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Several referred specimens were originally assigned to other genera

|

|

| Nanuqsaurus

|

2014

|

Prince Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( Alaska) Alaska)

|

Described as a dwarf tyrannosaurid although undescribed remains suggest a size comparable to Albertosaurus[61]

|

|

| Nasutoceratops

|

2013

|

Kaiparowits Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Possessed an enlarged nasal cavity and two long, curving horns similar to those of modern cattle

|

|

| Navajoceratops

|

2020

|

Kirtland Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Had a distinctive notch at the very top of its frill, similar to its potential ancestor Pentaceratops[62]

|

|

| Nedcolbertia

|

1998

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Known from three partial skeletons. The specific name, justinhofmanni, honors a six-year-old schoolboy who won a contest to have a dinosaur named after him

|

|

| Nevadadromeus

|

2022

|

Willow Tank Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Nevada) Nevada)

|

The first non-avian dinosaur described from Nevada

|

|

| Niobrarasaurus

|

1995

|

Niobrara Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian to Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Kansas) Kansas)

|

Originally mistakenly believed to have been aquatic[63]

|

|

| Nodocephalosaurus

|

1999

|

Kirtland Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Closely related to Asian ankylosaurids[64]

|

|

| Nodosaurus

|

1889

|

Frontier Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Coniacian)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Its armor included banded dermal plates interspersed by bony nodules

|

|

| Nothronychus

|

2001

|

Moreno Hill Formation, Tropic Shale (Late Cretaceous, Turonian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico New Mexico

Utah) Utah)

|

Would have lived in the marshes and swamps[65] along the Turonian shoreline[66]

|

|

| Ojoraptorsaurus

|

2011

|

Ojo Alamo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Only known from an incomplete pair of pubes

|

|

| Oohkotokia

|

2013

|

Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Potentially a synonym of Scolosaurus[67]

|

|

| Ornatops

|

2021

|

Menefee Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Preserves a pair of bumps on its skull which may have anchored a crest

|

|

| Ornitholestes

|

1903

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

May have possessed a sickle claw similar to those of dromaeosaurids[68]

|

|

| Ornithomimus

|

1890

|

Denver Formation, Dinosaur Park Formation, Ferris Formation?, Horseshoe Canyon Formation, Kaiparowits Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

Utah? Utah?

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

One referred specimen preserves impressions of ostrich-like feathers covering most of its body[69]

|

|

| Orodromeus

|

1988

|

Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Eggs considered to belong to this taxon may have actually come from a troodontid[70]

|

|

| Oryctodromeus

|

2007

|

Blackleaf Formation, Wayan Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Idaho Idaho

Montana) Montana)

|

Several specimens have been preserved in burrows

|

|

| Osmakasaurus

|

2011

|

Lakota Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian)

|

United States United States

( South Dakota) South Dakota)

|

Originally named as a species of Camptosaurus

|

|

| Pachycephalosaurus

|

1943

|

Hell Creek Formation, Lance Formation, Scollard Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta?) Alberta?)

United States United States

( Montana Montana

South Dakota South Dakota

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Possessed a tall, rounded head dome surrounded by bony knobs

|

|

| Pachyrhinosaurus

|

1950

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation, Prince Creek Formation, St. Mary River Formation, Wapiti Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Alaska) Alaska)

|

Three species have been named, each with a unique pattern of cranial ornamentation

|

|

| Palaeoscincus

|

1856

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Although many restorations depict it with the spikes of Edmontonia and the tail club of Ankylosaurus, this is most likely incorrect

|

|

| Panoplosaurus

|

1919

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Unlike other nodosaurids, it lacked enlarged spikes

|

|

| Parasaurolophus

|

1922

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Fruitland Formation, Kaiparowits Formation, Kirtland Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( New Mexico New Mexico

Utah) Utah)

|

Possessed a curved, hollow crest that varied in size between species

|

|

| Paraxenisaurus

|

2020

|

Cerro del Pueblo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Mexico Mexico

( Coahuila) Coahuila)

|

Described as the first deinocheirid from North America

|

|

| Parksosaurus

|

1937

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Had long toes which may be an adaptation to walking on soft soils in watercourses and marshlands[65]

|

|

| Paronychodon

|

1876

|

Hell Creek Formation, Judith River Formation, Lance Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( Montana Montana

North Dakota North Dakota

South Dakota South Dakota

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Only known from highly distinctive teeth

|

|

| Pawpawsaurus

|

1996

|

Paw Paw Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

Had enlarged nasal cavities that gave it an acute sense of smell, even more powerful than that of contemporary theropods[71]

|

|

| Pectinodon

|

1982

|

Hell Creek Formation, Lance Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Had comb-like serrations on its teeth

|

|

| Peloroplites

|

2008

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

One of the largest known nodosaurids

|

|

| Pentaceratops

|

1923

|

Fruitland Formation, Kirtland Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Its epijugal bones, the hornlets under its eyes, were relatively large

|

|

| Planicoxa

|

2001

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Early Cretaceous, Barremian to Albian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

The rear of its ilium was characteristically flat

|

|

| Platypelta

|

2018

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Originally assigned to Euoplocephalus but was given its own genus because of several morphological differences

|

|

| Platytholus

|

2023

|

Hell Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Differs from juveniles of the contemporary Pachycephalosaurus and Sphaerotholus, hence its classification as a new genus

|

|

| Podokesaurus

|

1911

|

Portland Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian to Sinemurian)

|

United States United States

( Massachusetts) Massachusetts)

|

May have had a tail one and a half times longer than the rest of its skeleton[72]

|

|

| Polyodontosaurus

|

1932

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

May be identical to Latenivenatrix[73]

|

|

| Polyonax

|

1874

|

Denver Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado) Colorado)

|

Poorly known

|

|

| Prenoceratops

|

2004

|

Oldman Formation, Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

The only basal neoceratopsian known from a bonebed

|

|

| Priconodon

|

1888

|

Arundel Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian)

|

United States United States

( Maryland) Maryland)

|

Large but only known from teeth

|

|

| Probrachylophosaurus

|

2015

|

Foremost Formation, Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Shows a skull morphology transitional between crestless and crested brachylophosaurins

|

|

| Propanoplosaurus

|

2011

|

Patuxent Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian)

|

United States United States

( Maryland) Maryland)

|

Only known from the imprints of a neonate skeleton

|

|

| Prosaurolophus

|

1916

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Had a relatively large head for a hadrosaur

|

|

| Protohadros

|

1998

|

Woodbine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Texas) Texas)

|

Possessed a downturned jaw which may be an adaptation to grazing on low-growing plants

|

|

| Pteropelyx

|

1889

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Potentially synonymous with Corythosaurus, although this cannot be confirmed due to the lack of cranial remains[74]

|

|

| Rativates

|

2016

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Originally described as a specimen of Struthiomimus

|

|

| Regaliceratops

|

2015

|

St. Mary River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Possessed a series of large, pentagonal plates lining its frill

|

|

| Richardoestesia

|

1990

|

Aguja Formation, Dinosaur Park Formation, Ferris Formation?, Hell Creek Formation?, Horseshoe Canyon Formation?, Lance Formation?, Scollard Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian?)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana? Montana?

Texas Texas

Wyoming?) Wyoming?)

|

Teeth assigned to this genus have been recovered all around the world, in deposits spanning from the Jurassic to the Cretaceous, although they may not represent a single taxon

|

|

| Rugocaudia

|

2012

|

Cloverly Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Some of this genus' remains include several caudal vertebrae

|

|

| Sarahsaurus

|

2011

|

Kayenta Formation (Early Jurassic, Sinemurian to Pliensbachian)

|

United States United States

( Arizona) Arizona)

|

Possessed strong hands which may indicate a feeding specialization

|

|

| Saurolophus

|

1912

|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Had a short, solid crest that pointed directly upwards. A larger, more well-known species has been found in Mongolia

|

|

| Sauropelta

|

1970

|

Cedar Mountain Formation?, Cloverly Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian)

|

United States United States

( Montana Montana

Utah? Utah?

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Its tail had at least forty vertebrae, making up half of its total body length

|

|

| Saurophaganax

|

1995

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico? New Mexico?

Oklahoma) Oklahoma)

|

Originally described as a large theropod, but was later suggested to be a chimera of sauropod and theropod bones. The holotype bone may have belonged to a sauropod[75]

|

|

| Sauroposeidon

|

2000

|

Antlers Formation, Cloverly Formation, Glen Rose Formation, Twin Mountains Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian)

|

United States United States

( Oklahoma Oklahoma

Texas Texas

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Could raise its head up to 18 metres (59 ft) in the air, the height of a six-story building[76]

|

|

| Saurornitholestes

|

1978

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Donoho Creek Formation, Kirtland Formation, Mooreville Chalk, Oldman Formation, Tar Heel/Coachman Formation, Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Alabama Alabama

Montana Montana

New Mexico New Mexico

South Carolina) South Carolina)

|

Its second premaxillary teeth could be adapted to preening feathers[77]

|

|

| Scolosaurus

|

1928

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Oldman Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Once widely believed to be synonymous with other Campanian ankylosaurids

|

|

| Scutellosaurus

|

1981

|

Kayenta Formation (Early Jurassic, Sinemurian)

|

United States United States

( Arizona) Arizona)

|

Had hundreds of osteoderms arranged in rows along its back and tail

|

|

| Segisaurus

|

1936

|

Navajo Sandstone (Early Jurassic, Pliensbachian to Toarcian)

|

United States United States

( Arizona) Arizona)

|

Preserves evidence of a wishbone similar to that of modern birds

|

|

| Seitaad

|

2010

|

Navajo Sandstone (Early Jurassic, Pliensbachian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

The holotype may have died when a sand dune collapsed on it[78]

|

|

| Siats

|

2013

|

Cedar Mountain Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Utah) Utah)

|

Large but inconsistent in phylogenetic placement

|

|

| Sierraceratops

|

2022

|

Hall Lake Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

United States United States

( New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

May be part of a unique clade of ceratopsians only known from southern Laramidia[79]

|

|

| Silvisaurus

|

1960

|

Dakota Formation (Early Cretaceous to Late Cretaceous, Albian to Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Kansas) Kansas)

|

Hypothesized to live in a forested habitat

|

|

| Smitanosaurus

|

2020

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Oxfordian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado) Colorado)

|

Only known from a partial skull and some vertebrae

|

|

| Sonorasaurus

|

1998

|

Turney Ranch Formation (Early Cretaceous to Late Cretaceous, Albian to Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Arizona) Arizona)

|

State dinosaur of Arizona

|

|

| Sphaerotholus

|

2002

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Frenchman Formation, Hell Creek Formation, Horseshoe Canyon Formation, Kirtland Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta Alberta

Saskatchewan) Saskatchewan)

United States United States

( Montana Montana

New Mexico) New Mexico)

|

Five species have been named, all known from skull elements. Lived in a broad range

|

|

| Spiclypeus

|

2016

|

Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Has been described as "boldly audacious"[80]

|

|

| Spinops

|

2011

|

Dinosaur Park Formation?/Oldman Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Described almost a century after its remains were collected

|

|

| Stegoceras

|

1902

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Fruitland Formation?, Kirtland Formation?, Oldman Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( New Mexico?) New Mexico?)

|

May have been an indiscriminate bulk-feeder due to the shape of its snout[81]

|

|

| Stegopelta

|

1905

|

Frontier Formation (Early Cretaceous to Late Cretaceous, Albian to Cenomanian)

|

United States United States

( Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

May have possessed a sacral shield similar to other nodosaurids

|

|

| Stegosaurus

|

1877

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( Colorado Colorado

Wyoming) Wyoming)

|

Had a single alternating row of large, kite-shaped plates

|

|

| Stellasaurus

|

2020

|

Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

United States United States

( Montana) Montana)

|

Possessed an enlarged, thickened nasal horn

|

|

| Stenonychosaurus

|

1932

|

Dinosaur Park Formation, Two Medicine Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

United States United States

( Montana?) Montana?)

|

Its brain-to-body mass ratio is one of the highest of any non-avian dinosaur

|

|

| Stephanosaurus

|

1914

|

Dinosaur Park Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian)

|

Canada Canada

( Alberta) Alberta)

|

Poorly known

|

|

| Stokesosaurus

|

1974

|

Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian? to Tithonian)

|

United States United States

( South Dakota? South Dakota?

Utah) Utah)

|