Insects in literature

|

Read other articles:

Kematian Hiakinthos, oleh Jean Broc. cakram yang membunuh Hiakinthos terlihat di dekat kakinya. Museum Sainte-Croix, Poitiers, Prancis. Hiakinthos (bahasa Yunani: Ὑάκινθος Hiákinthos) adalah seorang pahlawan ilahi dalam mitologi Yunani. Kultusnya di Amykles barat daya Sparta ada pada era Mycenaea. Sebuah temenos atau tempat suci dibangun di sekitar tempat yang dipercaya menjadi gundukan kuburnya, yang terletak di kaki patung Apollo pada periode Klasik.[1] Mitos sastra me...

Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: MA Negeri 3 Bantul – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR MA Negeri 3 BantulMAN Wonokromo BantulInformasiDidirikan1962AkreditasiA (96)Nomor Pokok Sekolah Nasional20363270MaskotMANTABA Madras...

Market and 1st StreetMarket and BatteryStreetcar at Market and 1st Street in 2016General informationLocationMarket Street at 1st and Battery StreetsSan Francisco, CaliforniaCoordinates37°47′28.3″N 122°23′58.3″W / 37.791194°N 122.399528°W / 37.791194; -122.399528Platforms2 side platformsTracks2ConstructionAccessiblePartial, Market and 1st Street (eastbound) only[1]HistoryRebuiltSeptember 1, 1995[2]Services Preceding station Muni Following sta...

Historic building in Salt Lake City, Utah, U.S. United States historic placeThomas Kearns Mansion and Carriage HouseU.S. National Register of Historic Places Governor's Mansion, March 2010Show map of UtahShow map of the United StatesLocation603 East South Temple StreetSalt Lake City, UtahUnited StatesCoordinates40°46′11″N 111°52′23″W / 40.76972°N 111.87306°W / 40.76972; -111.87306Area9 acres (3.6 ha)Built1900-02ArchitectNeuhausen, Carl M.NRHP refe...

See also: History of American journalism and Early American publishers and printers The history of American newspapers begins in the early 18th century with the publication of the first colonial newspapers. American newspapers began as modest affairs—a sideline for printers. They became a political force in the campaign for American independence. Following independence the first amendment to U.S. Constitution guaranteed freedom of the press. The Postal Service Act of 1792 provi...

Not to be confused with Beipu in Xincheng, Hualien. Place in Taiwan, Republic of ChinaBeipu Township北埔鄉 HoppoBeipu Township in Hsinchu CountyBeipu Township北埔鄉Coordinates: 24°39′50″N 121°4′5″E / 24.66389°N 121.06806°E / 24.66389; 121.06806CountryRepublic of ChinaProvinceTaiwanCountyHsinchuGovernment • TypeRural townshipArea • Total50.6676 km2 (19.5629 sq mi)Population (March 2023) • Total8,6...

Untuk kegunaan lain, lihat Ibis (disambiguasi). Ibis Ibis Klasifikasi ilmiah Kerajaan: Animalia Filum: Chordata Kelas: Aves Ordo: Ciconiiformes Famili: Threskiornithidae Subfamili: ThreskiornithinaePoche, 1904 Genera Threskiornis Pseudibis Thaumatibis Geronticus Nipponia Bostrychia Theristicus Cercibis Mesembrinibis Phimosus Eudocimus Plegadis Lophotibis Ibis, upih atau sekendi adalah sejenis burung yang masuk ke dalam famili Threskiornithidae. Ibis mempunyai paruh panjang bengkok dan biasany...

† Человек прямоходящий Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:Синапсиды�...

Questa voce sull'argomento myrtaceae è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Come leggere il tassoboxMelaleuca Melaleuca thymifolia Classificazione APG IV Dominio Eukaryota Regno Plantae (clade) Angiosperme (clade) Mesangiosperme (clade) Eudicotiledoni (clade) Eudicotiledoni centrali (clade) Superrosidi (clade) Rosidi (clade) Eurosidi (clade) Eurosidi II Ordine Myrtales Famiglia Myrtaceae Sottofamiglia Myrtoideae Tribù Melaleuceae Genere Mela...

Paris Métro station For other uses, see Bastille (disambiguation). BastilleLine 1 platforms.General informationLocationPl. de la Bastille (two)Boul. Bourdon × Boul. Henri IV37, Boul. Bourdon130, Rue de Lyon140, Rue de Lyon1, Rue de Charenton1, Boul. Beaumarchais2, Boul. Beaumarchais4th, 11th and 12th arrondissement of ParisÎle-de-FranceFranceCoordinates48°51′11″N 2°22′09″E / 48.853082°N 2.369077°E / 48.853082; 2.369077Owned byRATPOperated byRATPLine(s) L...

My Spy FamilyTitolo originaleMy Spy Family PaeseRegno Unito Anno2007-2010 Formatoserie TV Generesitcom Stagioni3 Episodi46 Durata22 min Lingua originaleinglese Rapporto14:9 CreditiIdeatorePaul Alexander Interpreti e personaggi Milo Twomey: Dirk Bannon Natasha Beaumont: Natalia Sterminov Alice Connor: Elle Bannon Joe Tracini: Spike Bannon Ignat Pakhotin: Boris Bannon Doppiatori e personaggi Danilo De Girolamo: Dirk Bannon Alessandra Korompay: Natalia Sterminov Gemma Donati: Elle Bannon Daniele...

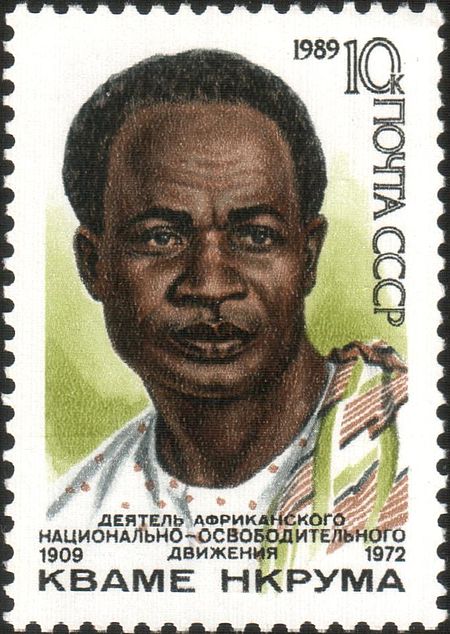

此條目可参照外語維基百科相應條目来扩充。若您熟悉来源语言和主题,请协助参考外语维基百科扩充条目。请勿直接提交机械翻译,也不要翻译不可靠、低品质内容。依版权协议,译文需在编辑摘要注明来源,或于讨论页顶部标记{{Translated page}}标签。 Osagyefo克瓦米·恩克鲁玛第三届非洲联盟主席任期1965年10月21日—1966年2月24日前任贾迈勒·阿卜杜-纳赛尔继任约瑟夫·亚瑟·�...

South Korean footballer and manager In this Korean name, the family name is Lee. Lee Hoe-taik Lee in 1972Personal informationFull name Lee Hoe-taikDate of birth (1946-10-11) 11 October 1946 (age 77)Place of birth Gimpo, Gyeonggi, KoreaHeight 1.67 m (5 ft 6 in)Position(s) ForwardYouth career1963 Yongdungpo Technical High School1963–1965 Dongbuk High SchoolCollege careerYears Team Apps (Gls)1966 Sungkyunkwan University 1970–1973 Hanyang University Senior career*Years Tea...

Військово-музичне управління Збройних сил України Тип військове формуванняЗасновано 1992Країна Україна Емблема управління Військово-музичне управління Збройних сил України — структурний підрозділ Генерального штабу Збройних сил України призначений для планува...

Music sales rankings by the trade magazine Billboard Billboard logo The Billboard charts tabulate the relative weekly popularity of songs and albums in the United States and elsewhere. The results are published in Billboard magazine. Billboard biz, the online extension of the Billboard charts, provides additional weekly charts,[1] as well as year-end charts.[2] The two most important charts are the Billboard Hot 100 for songs and Billboard 200 for albums, and other charts may ...

Taman Nasional Serra dos ÓrgãosIUCN Kategori II (Taman Nasional)Formasi perbukitan dengan puncak Jari Tuhan di latar belakangnyaLetakBrasilKota terdekatTeresópolisKoordinat22°26′43.26″S 42°59′59.13″W / 22.4453500°S 42.9997583°W / -22.4453500; -42.9997583Luas110 km²Didirikan1939 Serra dos Órgãos (Organs Range, Range of the Organs) atau Jalur Organ adalah sebuah jajaran gunung di Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, yang dijadikan taman nasional pada tahun 1939. Dae...

1931 film The SqueakerDirected byMartin FričKarel LamačWritten byEdgar Wallace (novel)Rudolph CartierEgon EisOtto EisProduced byKarel LamačStarringLissy ArnaKarl Ludwig DiehlFritz RaspCinematographyOtto HellerEdited byAlwin EllingHeinz RitterProductioncompanyOndra-Lamac-FilmDistributed bySüd-FilmRelease date 30 July 1931 (1931-07-30) Running time70 minutesCountryGermanyLanguageGerman The Squeaker (German: Der Zinker) is a 1931 German crime film directed by Martin Frič and ...

تلال رأس كوه الموقع باكستان إحداثيات 28°49′43″N 65°11′42″E / 28.82853056°N 65.19495278°E / 28.82853056; 65.19495278 تعديل مصدري - تعديل تلال رأس كوه، هي مجموعة من التلال الجرانيتية التي تشكل جزءًا من سلسلة جبال سليمان [الإنجليزية] في منطقة تشاغاي [الإنجليزية] في مقاطعة بلوش�...

Spiaggia di Travemünde, con le caratteristiche sedie da spiaggia a baldacchino (Strandkörbe in tedesco) Veliero Passat a Travemünde Travemünde: edifici a graticcio nell'Altstadt (città vecchia) Travemünde è un distretto di Lubecca, in Germania, alla foce del fiume Trave nella Baia di Lubecca. Famosa meta balneare del turismo locale sia attualmente che già in passato. Infatti Travemünde era un vecchio resort balneare (già dal 1802) ed è ad oggi il più grande porto di traghetti tede...

Cộng hòa Guatemala Tên bằng ngôn ngữ chính thức República de Guatemala (tiếng Tây Ban Nha) Quốc kỳ Huy hiệu Bản đồ Vị trí của Guatemala Tiêu ngữLibre Crezca Fecundo (tiếng Tây Ban Nha: Tiến tới tự do và màu mỡ)Quốc caHimno Nacional de Guatemala(Tiếng Việt: Quốc ca Guatemala)Hành khúc quốc gia: La GranaderaHành chínhChính phủCộng hòa dân chủTổng thốngBernardo ArévaloThủ đôThành phố Guatemala14°38′B 90°...