HMS Nicator (1916)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Bermeo merupakan nama kota di Spanyol yang terletak di bagian utara. Kota ini terletak di Wilayah Otonomi Pais Vasco, Provinsi Vizcaya, Spanyol. Pada tahun 2012, kota ini memiliki jumlah penduduk sebanyak 17.144 jiwa dan memiliki luas wilayah 34,12 km². Kota ini terletak 33 km dari Bilbao. Bermeo Pelabuhan Bermeo Pelabuhan Bermeo Pelabuhan Bermeo San Juan de Gaztelugatxe Akatz Izaro Olatu Xixili Badatoz Santa Eufemia Ercilla Aritzatxu Artikel bertopik geografi atau tempat Spanyol ...

Часть серии статей о Холокосте Идеология и политика Расовая гигиена · Расовый антисемитизм · Нацистская расовая политика · Нюрнбергские расовые законы Шоа Лагеря смерти Белжец · Дахау · Майданек · Малый Тростенец · Маутхаузен ·&...

Kementerian Perang Bayern di Munich, 1833 Kementerian Perang (Jerman: Kriegsministeriumcode: de is deprecated ) adalah sebuah kemeterian untuk urusan militer Kerajaan Bayern, yang didirikan sebagai Ministerium des Kriegswesens pada 1 Oktober 1808 oleh Raja Maksimilian I Yusuf dari Bayern. Kementerian tersebut terletak di Ludwigstraße[1] di Munich. Pada saat ini, bangunan tersebut, yang dibangun oleh Leo von Klenze antara 1824 dan 1830, menjadi kantor rekaman publik Bayern, Bayerische...

Artikel ini berisi konten yang ditulis dengan gaya sebuah iklan. Bantulah memperbaiki artikel ini dengan menghapus konten yang dianggap sebagai spam dan pranala luar yang tidak sesuai, dan tambahkan konten ensiklopedis yang ditulis dari sudut pandang netral dan sesuai dengan kebijakan Wikipedia. (April 2019) Logo Ovi. Ovi by Nokia adalah merek layanan Internet Nokia yang dapat digunakan dari peranti bergerak, komputer (melalui Nokia Ovi Suite) atau situs web (Ovi.com). Nokia berfokus pada lim...

Disambiguazione – Se stai cercando altri significati, vedi Uppsala (disambigua). Uppsalaarea urbana Uppsala – VedutaStazione, Orto botanico, UKK, Cattedrale, centro città LocalizzazioneStato Svezia RegioneSvealand Contea Uppsala ComuneUppsala AmministrazioneSindacoErik Pelling (S/SAP) dal 2018 TerritorioCoordinate59°51′N 17°38′E / 59.85°N 17.633333°E59.85; 17.633333 (Uppsala)Coordinate: 59°51′N 17°38′E / 59.85°N 17.6...

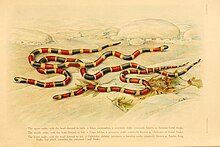

Use of mimicry as an anti-predator adaptation in animals with backbones This article relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this article by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: Mimicry in vertebrates – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) In evolutionary biology, mimicry in vertebrates is mimicry by a vertebrate of some model (an anim...

SalpausselkäSalpausselän hyppyrimäet Stato Finlandia LocalitàLahti Apertura1923 Ristrutturazioni1938, 1957,1974-1977 Spettatori80.000 Trampolino lungo HS 130Punto K116 m Primato138 m(Johann André Forfang, 2016) Trampolino normale HS 100Punto K90 m Primato103,5 m(Kamil Stoch, 2017) Trampolino medio HS 70Punto K64 m Primato62,5 m(Jarkko Määttä, 2008) Modifica dati su Wikidata · ManualeCoordinate: 60°59′00.5″N 25°37′53.39″E / 60.983471�...

此條目可参照英語維基百科相應條目来扩充。 (2021年5月6日)若您熟悉来源语言和主题,请协助参考外语维基百科扩充条目。请勿直接提交机械翻译,也不要翻译不可靠、低品质内容。依版权协议,译文需在编辑摘要注明来源,或于讨论页顶部标记{{Translated page}}标签。 约翰斯顿环礁Kalama Atoll 美國本土外小島嶼 Johnston Atoll 旗幟颂歌:《星條旗》The Star-Spangled Banner約翰斯頓環礁�...

Independent TV station in Minneapolis KSTC-TVMinneapolis–Saint Paul, MinnesotaUnited StatesCityMinneapolis, MinnesotaChannelsDigital: 30 (UHF)Virtual: 5.2Branding45tv; 5 Eyewitness News on 45MeTV Twin Cities (DT3)ProgrammingAffiliations5.2: Independent / ABC (alternate)for others, see § SubchannelsOwnershipOwnerHubbard Broadcasting(KSTC-TV, LLC)Sister stationsKSTP-TV, KSTP, KSTP-FM, KTMYHistoryFirst air dateJune 19, 1994 (29 years ago) (1994-06-19)Former call signsKVBM (...

提示:此条目页的主题不是中國—瑞士關係。 關於中華民國與「瑞」字國家的外交關係,詳見中瑞關係 (消歧義)。 中華民國—瑞士關係 中華民國 瑞士 代表機構駐瑞士台北文化經濟代表團瑞士商務辦事處代表代表 黃偉峰 大使[註 1][4]處長 陶方婭[5]Mrs. Claudia Fontana Tobiassen 中華民國—瑞士關係(德語:Schweizerische–republik china Beziehungen、法�...

Ordo Isabella orang Katolik (bahasa Spanyol: Orden de Isabel la Católica) adalah sebuah ordo sipil Spanyol yang diberikan untuk menghargai pelayanan yang bermanfaat bagi negara. Ordo tersebut tidak secara khusus diberikan kepada orang Spanyol, dan penghargaan tersebut telah diberikan pada beberapa warga asing. Ordo tersebut dibuat pada 14 Maret 1815 oleh Raja Ferdinand VII dari Spanyol untuk menghormati Ratu Isabella I dari Castile dengan nama Ordo Kerajaan dan Amerika Isabella orang Ka...

烏克蘭總理Прем'єр-міністр України烏克蘭國徽現任杰尼斯·什米加尔自2020年3月4日任命者烏克蘭總統任期總統任命首任維托爾德·福金设立1991年11月后继职位無网站www.kmu.gov.ua/control/en/(英文) 乌克兰 乌克兰政府与政治系列条目 宪法 政府 总统 弗拉基米尔·泽连斯基 總統辦公室 国家安全与国防事务委员会 总统代表(英语:Representatives of the President of Ukraine) 总...

Music radio station in Prescott, Arizona KAHMSpring Valley, ArizonaBroadcast areaPrescott–Flagstaff–PhoenixFrequency102.1 MHzBrandingFM 102.1ProgrammingFormatBeautiful Music - Easy ListeningOwnershipOwnerFarmworker Educational Radio Network (Cesar Chavez Foundation)(Phoenix Radio Broadcasting, LLC)Sister stationsKYCAHistoryFirst air dateSeptember 9, 1981; 42 years ago (1981-09-09)Former frequencies103.9 MHz (1980s)Call sign meaningThe call letters KAHM, when spoken as a ...

Star Wars character Fictional character Fennec ShandStar Wars characterMing-Na Wen as Fennec ShandFirst appearanceChapter 5: The GunslingerThe Mandalorian(2019)Last appearanceBad TerritoryStar Wars: The Bad Batch(2024)Created byJon FavreauPortrayed byMing-Na WenVoiced byMing-Na WenIn-universe informationSpeciesHuman (cyborg)OccupationAssassin, bounty hunter, consigliereAffiliationFett gotraPartnerBoba Fett Fennec Shand is a fictional character in the Star Wars franchise portrayed by Ming-Na W...

American animator, producer and entrepreneur (1901–1966) For other uses, see Walt Disney (disambiguation). Walt DisneyDisney in 1946Born(1901-12-05)December 5, 1901Chicago, Illinois, U.S.DiedDecember 15, 1966(1966-12-15) (aged 65)Burbank, California, U.S.Occupations Animator film producer voice actor entrepreneur TitlePresident of The Walt Disney Company[1]Spouse Lillian Bounds (m. 1925)Children2, including Diane Disney MillerRelativesDisney famil...

Buddhist precepts kept on observance days and festivals Buddhist devotional practices Devotional Offerings Prostration Merit-making Taking refuge Chanting / Music Pūja Holidays Buddha's Birthday Vesak Ghost Festival Uposatha Kaṭhina Precepts Five Precepts Eight Precepts Bodhisattva vow Bodhisattva Precepts Other Meditation Giving Texts Pilgrimage Fasting vte In Buddhism, the eight precepts (Sanskrit: aṣṭāṇga-śīla or aṣṭā-sīla, Pali: aṭṭhaṅga-sīla or aṭṭha-sīla) ...

第三十二届夏季奥林匹克运动会場地單車女子個人爭先比賽比賽場館伊豆單車館日期2021年8月6日至8日参赛选手30(含未上场1人)位選手,來自18個國家和地區奖牌获得者01 ! 凱爾西·米切爾 加拿大02 ! 奧蓮娜·斯塔里科娃 乌克兰03 ! 李慧詩 中国香港← 20162024 → 2020年夏季奧林匹克運動會自行車比賽 公路自行车 公路賽 男子 女子 �...

2015 Gibraltar general election ← 2011 26 November 2015 2019 → All 17 seats in the Gibraltar Parliament9 seats needed for a majority First party Second party Leader Fabian Picardo Daniel Feetham Party Alliance Social Democrats Last election 48.88%, 10 seats 46.76%, 7 seats Seats won 10 7 Seat change Popular vote 100,950 46,545 Percentage 68.44% 31.56% Swing 19.56pp 15.20pp Chief Minister before election Fabian Picardo Socialist Lab...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant la médecine. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Pour les articles homonymes, voir Bridge (homonymie). Dents de porcelaine fixées sur un pont de métal (Porcelain Fused to Metal ou PFM). Un bridge ou pont dentaire au Québec et Nouveau-Brunswick ou prothèse partielle fixe[1] est une prothèse dentaire formant un pont entre deux dents. Le bridge permet de rem...

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Februari 2023. RookseDesaPohon elm di RookseKoordinat: Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:ISO 3166/data/EE' not found.NegaraEstoniaCountyTartuParokiKastreZona waktuUTC+2 (EET) • Musim panas (DST)UTC+3 (EEST) Rookse adalah sebuah desa di ...