Filipinos in Ireland

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Village in County Galway, Ireland Village in Connacht, IrelandAughrim EachroimVillageAughrim crossAughrimLocation in IrelandCoordinates: 53°18′15″N 8°19′00″W / 53.304167°N 8.316667°W / 53.304167; -8.316667CountryIrelandProvinceConnachtCountyCounty GalwayElevation115 m (377 ft)Population (2011)[1] • Rural595Time zoneUTC+0 (WET) • Summer (DST)UTC+1 (IST (WEST))Irish Grid ReferenceM785281Websitewww.loughrea.ie Aug...

Untuk perguruan tinggi negeri, swasta (termasuk Islam swasta), dan kedinasan, lihat Daftar perguruan tinggi di Indonesia. Perguruan Tinggi Keagamaan Islam Negeri (PTKIN), merupakan bagian dari Perguruan Tinggi Keagamaan Negeri yang berberada di bawah tanggung jawab Kementerian Agama. Ada tiga jenis perguruan tinggi yang termasuk ke dalam kategori ini, yaitu universitas Islam negeri (UIN), institut agama Islam negeri (IAIN), dan sekolah tinggi agama Islam negeri (STAIN). Saat ini PTKIN berjuml...

August EigruberAugust Eigruber pada tahun 1938 Gauleiter Reichsgau OberdonauMasa jabatan22 Mei 1938 – 5 Mei 1945Reichsstatthalter Reichsgau OberdonauMasa jabatan1 April 1940 – 5 Mei 1945Landeshauptmann Austria HuluMasa jabatan14 Mei 1938 – 1 April 1940 PendahuluHeinrich GleissnerPenggantiJabatan dihapuskan Informasi pribadiLahir(1907-04-16)16 April 1907Steyr, AustriaMeninggal28 Mei 1947(1947-05-28) (umur 40)Penjara Landsberg, Landsberg am LechSebab k...

Historic house in Connecticut, United States United States historic placeEphraim Wheeler HouseU.S. National Register of Historic Places Show map of ConnecticutShow map of the United StatesLocation470 Whippoorwill Lane,Stratford, ConnecticutCoordinates41°15′11.3″N 73°6′55.35″W / 41.253139°N 73.1153750°W / 41.253139; -73.1153750Architectural styleColonialNRHP reference No.92000318[1]Added to NRHPApril 17, 1992 The Ephraim Wheeler House ...

Anglo-Irish lawyer The Right HonourableThe Lord AshbournePC KCLord Ashbourne, by Dickinson.Lord Chancellor of IrelandIn office1885–1886MonarchVictoriaPreceded byJohn NaishSucceeded byJohn NaishIn office1886–1892MonarchVictoriaPreceded byJohn NaishSucceeded bySamuel WalkerIn office1895–1905MonarchsVictoriaEdward VIIPreceded bySamuel WalkerSucceeded bySamuel WalkerAttorney-General for IrelandIn office1877–1880MonarchVictoriaPreceded byGeorge Augustus Chichester MaySucceeded byHugh LawMe...

Register office of Northern Ireland This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: General Register Office Northern Ireland – news · newspapers · books · s...

كأس الاتحاد الإنجليزي 1913–14 تفاصيل الموسم كأس الاتحاد الإنجليزي النسخة 43 البلد المملكة المتحدة التاريخ بداية:13 سبتمبر 1913 نهاية:25 أبريل 1914 المنظم الاتحاد الإنجليزي لكرة القدم البطل نادي بيرنلي عدد المشاركين 64 كأس الاتحاد الإنجليزي 1912–13 كأس ا...

Indian national monument dedicated to its armed forces National War Memorial IndiaClockwise from top: The Stambh (obelisk) houses the immortal flame, A section of the Tyag Chakra, View of a bust at the Param Vir Chakra sectionFor Indian military dead of all warsEstablished2019Unveiled25 February 2019Location28°36′46″N 77°13′59″E / 28.612772°N 77.233053°E / 28.612772; 77.233053C Hexagon, India Gate Circle, New Delhi, IndiaDesigned byYogesh Chandrah...

Sulayman ibn QutulmishMonumento dedicato a Sulayman ibn Qutulmish a Tarso, in Turchiasultano di RumIn carica1077 - 1086 PredecessoreQutulmish SuccessoreQilij Arslan I Altri titolisciàghazi Mortepressi di Antiochia, 1086 DinastiaSelgiuchidi PadreQutulmish ConsorteSeljuka Khatun Religionesunnismo Sulayman ibn Qutulmish, o Süleyman I (in arabo سليمان بن قتلمش?, Sulaymān ibn Qutulmish, o Qutalmish; ... – pressi di Antiochia, 1086), fondò uno Stato indipendente...

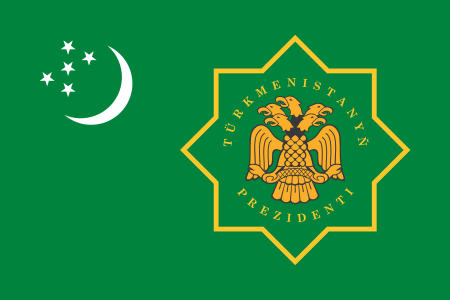

土库曼斯坦总统土库曼斯坦国徽土库曼斯坦总统旗現任谢尔达尔·别尔德穆哈梅多夫自2022年3月19日官邸阿什哈巴德总统府(Oguzkhan Presidential Palace)機關所在地阿什哈巴德任命者直接选举任期7年,可连选连任首任萨帕尔穆拉特·尼亚佐夫设立1991年10月27日 土库曼斯坦土库曼斯坦政府与政治 国家政府 土库曼斯坦宪法 国旗 国徽 国歌 立法機關(英语:National Council of Turkmenistan) ...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Bakayoko. Tiémoué Bakayoko Tiémoué Bakayoko avec le Chelsea FC (2017). Situation actuelle Équipe FC Lorient Numéro 14 Biographie Nationalité Français Ivoirien Nat. sportive Français Naissance 17 août 1994 (29 ans) Paris (France) Taille 1,89 m (6′ 2″) Période pro. 2013 - Poste Milieu défensif Pied fort Droit Parcours junior Années Club 2000-2004 Olympique de Paris XVe 2004-2006 CA Paris 14 2006-2008 Montrouge FC 92 2008-2013 St...

此条目序言章节没有充分总结全文内容要点。 (2019年3月21日)请考虑扩充序言,清晰概述条目所有重點。请在条目的讨论页讨论此问题。 哈萨克斯坦總統哈薩克總統旗現任Қасым-Жомарт Кемелұлы Тоқаев卡瑟姆若马尔特·托卡耶夫自2019年3月20日在任任期7年首任努尔苏丹·纳扎尔巴耶夫设立1990年4月24日(哈薩克蘇維埃社會主義共和國總統) 哈萨克斯坦 哈萨克斯坦政府...

东部机场集团有限公司Eastern Airports公司類型国有企业机构代码91320000134795187R (查)公司前身南京禄口国际机场有限公司成立1997年6月10日代表人物董事长:钱凯法(代理)总经理:周成益總部 中国江苏省南京市江宁区禄口街道南京禄口国际机场業務範圍航空运输业所有權者江苏省人民政府(通过省国资委和省交通控股71.3%)南京市人民政府(通过紫金投资控股28.7%)主要�...

Polish actor (1928–1986) Wirgiliusz GryńBorn(1928-06-09)9 June 1928Dąbrowa Górnicza, PolandDied3 September 1986(1986-09-03) (aged 58)Warsaw, PolandOccupationActorYears active1964-1986 Grave of Wirgiliusz Gryń at the Doły Cemetery in Łódź Wirgiliusz Gryń (9 June 1928 – 3 September 1986) was a Polish actor.[1] He appeared in more than 60 films and television shows between 1964 and 1986. At the 13th Moscow International Film Festival he won the award for Best ...

Church in Virginia, United StatesMcLean Bible Church (MBC)MBC's LogoLocation8925 Leesburg Pike, Vienna, VirginiaCountryUnited StatesDenominationNon-denominational evangelicalWeekly attendance~8,000 (2022) [1]Websitewww.mcleanbible.orgHistoryStatus501(c)(3)[2]Founded1961; 63 years ago (1961)ClergySenior pastor(s)Mike Kelsey, Jr., Lead Pastor David Platt, Lead PastorPastor(s) Wade Burnett (Executive Pastor) Nathan Reed (Tysons Campus pastor) Todd Peters (Prince...

2001年洲際國家盃대한민국/일본 2001년 2001 韓国/日本賽事資料屆數第 5 屆主辦國南韓日本比賽日期5月30日–6月10日參賽隊數8 隊(來自6個大洲)球場6 個(位於6個城市)衛冕球隊 墨西哥最終成績冠軍 法國(第 1 次奪冠)亞軍 日本季軍 澳大利亞殿軍 巴西賽事統計比賽場數16 場總入球數31 球(場均 1.94 球)入場人數557,191 人(場均 34,824 人)最佳射手 卡利尼 桑·梅菲 皮利斯 �...

Drag king or drag queen performance show Drag show at the Stonewall Discotheque in Miami Beach, Florida, in 1972Cross-dressing History of cross-dressing In wartime History of drag Rebecca Riots Casa Susanna Pantomime dame Principal boy Travesti (theatre) Travesti (gender identity) Key elements Passing Transvestism Modern drag culture Ball culture Drag king Drag pageantry Drag queen Female queen (drag) Sexual practices Femdom Feminization Petticoating Transvestic fetishism Other aspects Cross-...

1933 Western Australian state election ← 1930 8 April 1933 1936 → All 50 seats in the Western Australian Legislative Assembly First party Second party Leader Philip Collier James Mitchell Party Labor Nationalist/Country coalition Leader since 16 April 1917 17 May 1919 Leader's seat Boulder Northam (lost seat) Last election 23 seats 27 seats Seats won 30 seats 19 seats Seat change 7 8 Percentage 45.48% 44.82% Swing 7.08 10.13 Premie...

Cet article présente une liste des présidents de la république de Lituanie. Présidents successifs Nom Début du mandat Fin du mandat Parti politique Aleksandras Stulginskis 21 décembre 1922 7 juin 1926 Parti démocrate chrétien lituanien Kazys Grinius 7 juin 1926 18 décembre 1926 Union lituanienne agraire et des verts Jonas Staugaitis 18 décembre 1926 19 décembre 1926 Union lituanienne agraire et des verts Aleksandras Stulginskis 19 décembre 1926 Parti démocrate chrétien lituanien...

Karikatur karya George Cruikshank yang menggambarkan kekejaman guillotine. Pemerintahan Teror juga dikenal secara singkat sebagai Teror (bahasa Prancis: La Terreur) merupakan masa penuh kekerasan selama 11 bulan selama Revolusi Prancis. Selama masa ini, orang Prancis yang tidak mendukung revolusi dipancung dengan guillotine. Guillotine (Pisau Nasional) itu menjadi simbol rentetan eksekusi sejumlah tokoh terkemuka, seperti Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, Girondin, Louis Philippe II dan Madame...