EPOXI

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Roman general's address to his soldiers The Augustus of Prima Porta is an example of an adlocutio pose. In ancient Rome the Latin word adlocutio means an address given by a general, usually the emperor, to his massed army and legions, and a general form of Roman salute from the army to their leader. The research of adlocutio focuses on the art of statuary and coinage aspects. It is often portrayed in sculpture, either simply as a single, life-size contrapposto figure of the general with his a...

Biografi ini tidak memiliki sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak dapat dipastikan. Bantu memperbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan sumber tepercaya. Materi kontroversial atau trivial yang sumbernya tidak memadai atau tidak bisa dipercaya harus segera dihapus.Cari sumber: Annette Bening – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR (Pelajari cara dan kapan saatnya untuk menghapus pesan templat ini) Annette BeningAnnette Bening di Festival Film ...

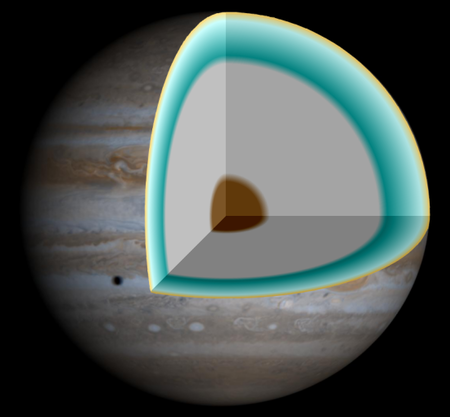

Gambar potongan yang menunjukkan model interior Jupiter, dengan inti berbatu yang dilapisi oleh lapisan dalam hidrogen metalik. Dalam ilmu keplanetan, volatil atau pemeruap adalah kelompok unsur kimia dan senyawa kimia dengan volatilitas rendah yang berhubungan dengan planet atau kerak bulan dan / atau atmosfer. Contohnya termasuk nitrogen, air, karbon dioksida, amonia, hidrogen, metana dan sulfur dioksida. Dalam astrogeologi, senyawa ini keadaan padat, sering terdiri dari proporsi besar dari...

وايتيش الإحداثيات 37°47′18″N 88°55′35″W / 37.7883°N 88.9264°W / 37.7883; -88.9264 [1] تاريخ التأسيس 1903 تقسيم إداري البلد الولايات المتحدة[2] التقسيم الأعلى إلينوي خصائص جغرافية المساحة 2.33 كيلومتر مربع عدد السكان عدد السكان 279 (1 أبريل 2020)[3] ا�...

جائزة النمسا الكبرى 1986 (بالألمانية: XIX Holiday Austrian Grand Prix) السباق 12 من أصل 16 في بطولة العالم لسباقات الفورمولا واحد موسم 1986 السلسلة بطولة العالم لسباقات فورمولا 1 موسم 1986 البلد النمسا التاريخ 17 أغسطس 1986 مكان التنظيم ستيفن سبيلبرغ، شتايرمارك، النمسا طول المسار 5.942 ...

Collection of illustrated, pocket-sized books on a variety of subjects New Horizons (book series) redirects here. Not to be confused with New Horizons (book) or New Horizons. Découvertes GallimardFour titles from the collection, first row from left to right — Les feux de la Terre : Histoires de volcans, L'Afrique des explorateurs : Vers les sources du Nil, Tous les jardins du monde and Figures de l'héraldique; and their English editions published in the corresponding American an...

الدوري الألماني الشرقي 1969–70 تفاصيل الموسم الدوري الألماني الشرقي النسخة 23 البلد ألمانيا الشرقية التاريخ بداية:23 أغسطس 1969 نهاية:30 مايو 1970 المنظم الاتحاد الأوروبي لكرة القدم البطل كارل زايس يينا مباريات ملعوبة 182 عدد المشاركين 14 الدوري الألم�...

German Jewish industrialist Hall in the house of Max Meirowsky in Cologne-Lindenthal. With a tapestry by Fritz Erler (1909) Max Meirowsky (born 17 February 1866 in Guttstadt; died 1 December 1949 in Geneva) was a German-Jewish industrialist and art collector persecuted by the Nazis. Life Max Meirowsky, the older brother of the dermatologist Emil Meirowsky (1876-1960),[1] came to Cologne from East Prussia. In 1894 he founded a company near Porz to produce insulating material (mica, mon...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir bus et Bus (électricité). Flotte d'autobus électriques à Pékin pendant les Jeux olympiques de 2008 Un bus électrique est un véhicule de type autobus qui fonctionne grâce à l’énergie électrique pour assurer un service de transport de voyageurs. Il se distingue du trolleybus et du gyrobus par le fait qu’il est indépendant de tout circuit d’alimentation (type caténaire) et possède sa propre réserve d’énergie, sous forme de batteries emba...

Designation for a radio broadcasting frequency This article appears to be a dictionary definition. Please rewrite it to present the subject from an encyclopedic point of view. (May 2023) In broadcasting, a channel or frequency channel is a designated radio frequency (or, equivalently, wavelength), assigned by a competent frequency assignment authority for the operation of a particular radio station, television station or television channel. See also Frequency allocation, ITU RR, article 1.17 ...

本條目存在以下問題,請協助改善本條目或在討論頁針對議題發表看法。 此條目需要擴充。 (2013年1月1日)请協助改善这篇條目,更進一步的信息可能會在討論頁或扩充请求中找到。请在擴充條目後將此模板移除。 此條目需要补充更多来源。 (2013年1月1日)请协助補充多方面可靠来源以改善这篇条目,无法查证的内容可能會因為异议提出而被移除。致使用者:请搜索一下条目的...

博里萨夫·约维奇攝於2009年 南斯拉夫社會主義聯邦共和國第12任總統任期1990年5月15日—1991年5月15日总理安特·马尔科维奇前任亚内兹·德尔诺夫舍克继任塞吉多·巴伊拉莫维奇(英语:Sejdo Bajramović) (代任)第12任不结盟运动秘书长任期1990年5月15日—1991年5月15日前任亚内兹·德尔诺夫舍克继任斯捷潘·梅西奇第3任塞尔维亚常驻南斯拉夫社会主义联邦共和国主席团代表任�...

Royal Air Force Air Chief Marshal (born 1939) For the NASCAR driver, see Richard Johns (racing driver). For the film and television producer, see Richard Johns (producer). Sir Richard JohnsSir Richard Johns, the Constable and Governor of Windsor Castle, leading the procession to the Garter service in St George's Chapel at Windsor CastleBorn (1939-07-28) 28 July 1939 (age 84)Horsham, West Sussex, EnglandAllegianceUnited KingdomService/branchRoyal Air ForceYears of service1959–2000R...

القوات المسلحة المصريةإدارة نظم المعلومات تفاصيل الوكالة الحكومية البلد مصر الاسم الكامل إدارة نظم المعلومات للقوات المسلحة المصرية المركز القاهرة، مصر الإدارة المدير التنفيذي لواء / توفيق مختار توفيق، مدير إدارة نظم المعلومات للقوات المسلحة المصرية تعديل مصدري...

Species of fish Colorado pikeminnow Conservation status Vulnerable (IUCN 3.1)[1] Critically Imperiled (NatureServe)[2] Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Actinopterygii Order: Cypriniformes Family: Cyprinidae Subfamily: Leuciscinae Clade: Laviniinae Genus: Ptychocheilus Species: P. lucius Binomial name Ptychocheilus luciusGirard, 1856 The Colorado pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus lucius, formerly squawfish) is the la...

Governor of the Province of South Carolina (1701-1777) For the Canadian parliamentarian, see James Allison Glen. For the Canadian flying ace, see James Alpheus Glen. James Glen25th Governor of South CarolinaIn officeDecember 17, 1743 – June 1, 1756MonarchGeorge IIPreceded byWilliam BullSucceeded byWilliam Henry Lyttelton Personal detailsBorn1701Linlithgow, ScotlandDied(1777-07-18)July 18, 1777London, England James Glen (1701 – July 18, 1777) was a Scottish politician in the Provi...

National sports team KoreaCaptainHeesung ChungITF ranking27 (20 September 2021)Colorsred & whiteFirst year1960Years played59Ties played (W–L)114 (51-63)Years inWorld Group3 (0-3)Best finishWG 1r (1981, 1987 & 2008)Most total winsHyung-Taik Lee (51-24)Most singles winsHyung-Taik Lee (41-9)Most doubles winsJin-Sun Yoo (10-6)Hyung-Taik Lee (10-15)Best doubles teamJin-Sun Yoo and Bong-Soo Kim (5-1)Most ties playedHyung-Taik Lee (31)Most years playedHyung-Taik Lee (15) The South Korea me...

American politician (1840–1927) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Archibald B. Darragh – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Archibald B. DarraghArchibald B. Darragh photographed by C. M. Bell StudioMember of the U.S. House&#...

JFK-era advisory body to the U.S. president External videos Prospects of Mankind with Eleanor Roosevelt; What Status For Women?, 59:07, 1962.Eleanor Roosevelt, chair of the Commission, interviews President John F. Kennedy, Secretary of Labor Arthur Goldberg and others, Open Vault from WGBH[1] The President's Commission on the Status of Women (PCSW) was established to advise the President of the United States on issues concerning the status of women. It was created by John F. Kennedy's...

Questa voce sull'argomento stagioni delle società calcistiche italiane è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Voce principale: Associazione Sportiva Gubbio 1910. A.S. Gubbio 1910Stagione 2002-2003Sport calcio Squadra Gubbio Allenatore Marco Alessandrini Presidente Giovanni Urbani Serie C23º posto nel girone B. Maggiori presenzeCampionato: Fabbri (34) Miglior marcatoreCampionato: Cipolla...