Bloomsbury (horse)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Bad Essen Lambang kebesaranLetak Bad Essen di Osnabrück NegaraJermanNegara bagianNiedersachsenKreisOsnabrückPemerintahan • MayorGünter Harmeyer (CDU)Luas • Total103,31 km2 (3,989 sq mi)Ketinggian113 m (371 ft)Populasi (2013-12-31)[1] • Total15.013 • Kepadatan1,5/km2 (3,8/sq mi)Zona waktuWET/WMPET (UTC+1/+2)Kode pos49152Kode area telepon05472Pelat kendaraanOSSitus webwww.badessen.de Bad Essen ialah se...

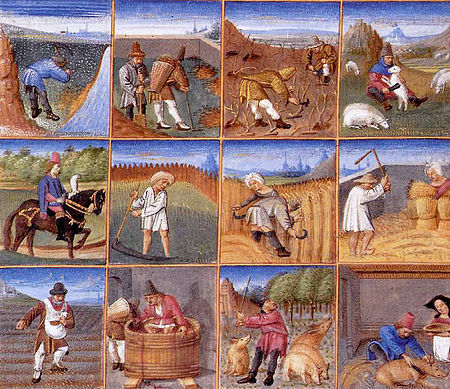

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Janvier (homonymie). Janvier Janvier, extrait des Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry (vers 1410-1416), musée Condé, Chantilly, ms.65, f.1. Éphémérides 1er 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 décembre février modifier Janvier est le premier mois des calendriers grégorien et julien, l'un des sept mois possédant 31 jours. Nom Étymologie Le nom de janvier provient du nom latin d...

Italian model, actress and film director Valeria GolinoBorn (1965-10-22) 22 October 1965 (age 58)Naples, ItalyNationalityItalian Greek[1]OccupationActressYears active1983–presentSpouse(s)Peter Del Monte (1985–1987)Benicio del Toro (1988–1992)Fabrizio Bentivoglio (1993–2001)Andrea Di Stefano (2002–2005)Riccardo Scamarcio (2006–2016)AwardsVolpi Cup for best actress – Venice Film Festival 1985: Storia d'amore 2015: For your loveWebsitewww.valeriagol...

For related races, see 1928 United States Senate elections. 1928 United States Senate election in California ← 1922 November 6, 1928 1934 → Nominee Hiram Johnson Minor Moore Charles H. Randall Party Republican Democratic Prohibition Popular vote 1,148,397 282,411 92,106 Percentage 74.11% 18.23% 5.94% County resultsJohnson: 60–70% 70–80% 80–90% &#...

العلاقات الإكوادورية التشيكية الإكوادور التشيك الإكوادور التشيك تعديل مصدري - تعديل العلاقات الإكوادورية التشيكية هي العلاقات الثنائية التي تجمع بين الإكوادور والتشيك.[1][2][3][4][5] مقارنة بين البلدين هذه مقارنة عامة ومرجعية للدولتين: �...

Rasio 1:2 Bendera Sao Tome dan Principe diperkenalkan pada 5 November 1975. Warna merah melambangkan kemerdekaan, dengan dua bintang hitam melambangkan dua pulau utama di negara itu. Hijau, kuning, dan merah merupakan warna bendera Pan-Afrika. lbsBendera di duniaBendera negara berdaulat · Daerah dependensiAfrika Afrika Selatan Afrika Tengah Aljazair Angola Benin Botswana Burkina Faso Burundi Chad Eritrea Eswatini Etiopia Gabon Gambia Ghana Guinea Guinea Khatulistiwa Guinea-Bissau Jibuti...

Roy Makaay Makaay dengan Feyenoord saat 2007Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Rudolphus Antonius MakaayTanggal lahir 9 Maret 1975 (umur 49)[1]Tempat lahir Wijchen, Belanda[1]Tinggi 188 m (616 ft 9+1⁄2 in)Posisi bermain PenyerangKarier junior SC Woezik DIOSA Blauw Wit NijmegenKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)1993–1997 Vitesse 109 (42)1997–1999 Tenerife 72 (21)1999–2003 Deportivo La Coruña 133 (79)2003–2007 Bayern Munich 129 (78)2007–2010 Fey...

Totò e CarolinaUna scena del filmLingua originaleitaliano Paese di produzioneItalia Anno1955 Durata80 minuti (versione censurata), 93 minuti (versione restaurata del 1999) Dati tecnicibianco e nerorapporto: 1,33:1 Generecommedia RegiaMario Monicelli SoggettoEnnio Flaiano SceneggiaturaAge, Furio Scarpelli, Rodolfo Sonego, Mario Monicelli ProduttoreAlfredo De Laurentiis Casa di produzioneRosa Film Distribuzione in italianoVariety Film FotografiaDomenico Scala, Luciano Trasatti MontaggioAdriana...

Women's long jump at the 2015 World ChampionshipsVenueBeijing National StadiumDates27 August (qualification)28 August (final)Competitors34 from 20 nationsWinning distance7.14Medalists Tianna Bartoletta United States Shara Proctor Great Britain Ivana Španović Serbia← 20132017 → Events at the2015 World ChampionshipsTrack events100 mmenwomen200 mmenwomen400 mmenwomen800 mmenwomen1500 mmenwomen5000 mm...

Ville-sur-TourbecomuneVille-sur-Tourbe – Veduta LocalizzazioneStato Francia RegioneGrand Est Dipartimento Marna ArrondissementSainte-Menehould CantoneArgonne Suippe et Vesle TerritorioCoordinate49°11′N 4°47′E / 49.183333°N 4.783333°E49.183333; 4.783333 (Ville-sur-Tourbe)Coordinate: 49°11′N 4°47′E / 49.183333°N 4.783333°E49.183333; 4.783333 (Ville-sur-Tourbe) Superficie11,22 km² Abitanti214[1] (2009) Densità19,07 ab...

Ulster loyalist attack in Northern Ireland 1991 Cappagh killingsPart of the TroublesLocationBoyle's Bar,Cappagh, County TyroneNorthern IrelandCoordinates54°32′29.40″N 6°55′27.19″W / 54.5415000°N 6.9242194°W / 54.5415000; -6.9242194Date3 March 1991 10:30 pmAttack typeShootingDeaths4Injured1PerpetratorUlster Volunteer Force The 1991 Cappagh killings was a gun attack by the loyalist Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) on 3 March 1991 in the village of Cappagh, County...

Subdivision in West Bengal, IndiaAlipore SadarSubdivisionInteractive Map Outlining Alipore Sadar SubdivisionCoordinates: 22°32′21″N 88°19′38″E / 22.5391712°N 88.3272782°E / 22.5391712; 88.3272782Country IndiaState West BengalDivisionPresidencyDistrictSouth 24 ParganasHeadquartersAliporeArea • Total427.28 km2 (164.97 sq mi)Elevation9 m (30 ft)Population (2011) • Total1,490,342 • Density3...

Television channel CTV News ChannelCountryRepublic of China (Taiwan)Broadcast areaTaiwanNetworkChina TelevisionHeadquartersTaipei City, TaiwanOwnershipSister channelsCTi NewsHistoryLaunchedJuly 1, 2004 CTV News Channel (Chinese: 中視新聞台; pinyin: Zhōng shì xīnwén tái) is a digital television channel operated by China Television (CTV) in Taiwan, launched on July 1, 2004. See also Media of Taiwan vteTelevision in TaiwanFree-to-air /TerrestrialTTV TTV Main Channel TTV Finance...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Villefort. Villefort Le barrage de Villefort. Blason Administration Pays France Région Occitanie Département Lozère Arrondissement Mende Intercommunalité CC Mont Lozère Maire Mandat Jean-Claude Bajac-Leyantou 2022-2026 Code postal 48800 Code commune 48198 Démographie Gentilé Villefortais Populationmunicipale 594 hab. (2021 ) Densité 81 hab./km2 Géographie Coordonnées 44° 26′ 25″ nord, 3° 55′ 58″ est...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento premi cinematografici non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Philippe Noiret è stato il primo vincitore del premio Joaquin Phoenix è l'unico attore ad avere vinto il premio due volte Il London Critics Circle Film Award all'attore dell'anno (London Film Criti...

Part of a series onChristianity JesusChrist Nativity Baptism Ministry Crucifixion Resurrection Ascension BibleFoundations Old Testament New Testament Gospel Canon Church Creed New Covenant Theology God Trinity Father Son Holy Spirit Apologetics Baptism Christology History of theology Mission Salvation Universalism HistoryTradition Apostles Peter Paul Mary Early Christianity Church Fathers Constantine Councils Augustine Ignatius East–West Schism Crusades Aquinas Reformation Luther Denominati...

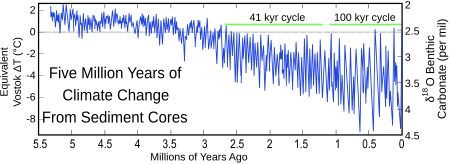

Overview of climactic conditions in Antarctica Surface temperature of Antarctica in winter and summer from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts The climate of Antarctica is the coldest on Earth. The continent is also extremely dry (it is a desert[1]), averaging 166 mm (6.5 in) of precipitation per year. Snow rarely melts on most parts of the continent, and, after being compressed, becomes the glacier ice that makes up the ice sheet. Weather fronts rarely p...

Serhiy SobkoSerhiy Sobko en uniforme de colonelBiographieNaissance 11 juillet 1984 (40 ans)LitynNom dans la langue maternelle Сергі́й Станісла́вович Собко́Nationalité ukrainienneAllégeance UkraineActivité Officier généralAutres informationsConflit Guerre du DonbassDistinctions Medal 15 years to the Armed Forces of Ukraine (d)Pamětní odznak Voják-mírotvůrce (d)Héros d'Ukraine, ordre de l'étoile d'ormodifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata Serh...

Ion containing two or more atoms This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Polyatomic ion – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) An electrostatic potential map of the nitrate ion (NO−3). Areas coloured translucent red, around the outs...

香港トラム 第4世代のNo. 50第4世代のNo. 50 堅尼地城總站 石塘咀總站 屈地街電車廠 港澳碼頭 上環(西港城)總站 上環 MTR港島線乗換 香港 轉乘港鐵 中環 MTR荃湾線・港島線乗換 中環碼頭 金鐘 MTR荃湾線・港島線乗換 湾仔 MTR港島線乗換 跑馬地總站 銅鑼湾 MTR港島線乗換 銅鑼湾總站 天后 MTR港島線乗換 炮台山 MTR港島線乗換 北角總站 北角 MTR港島線・将軍澳線乗換 北角碼頭 �...