Battus philenor

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

High rise apartment building in Louisville, KY, US The 800 ApartmentsThe 800 Apartments in 2006General informationStatusCompletedTypeResidentialArchitectural styleInternational Style[1]Location800 South Fourth StreetLouisville, Kentucky, 40201Coordinates38°14′37.85″N 85°45′32.77″W / 38.2438472°N 85.7591028°W / 38.2438472; -85.7591028Construction started1961Completed1963–64Opened1963Renovated2015–16Cost$6 millionHeightAntenna spire331 ft (10...

Daniel Garbercirca 1900Lahir(1880-04-11)11 April 1880North Manchester, IndianaMeninggal5 Juli 1958 ( 1958 -07-05) (umur 78)Cuttalossa, PennsylvaniaKebangsaanAmericanPendidikanPennsylvania Academy of the Fine ArtsDikenal ataslandscape painter Daniel Garber (11 April 1880 – 5 Juli 1958) adalah seorang pelukis lanskap Impresionis Amerika pelukis lanskap dan anggota koloni di New Hope, Pennsylvania. Dia terkenal hari ini karena adegan besar impresionis di daerah Harapan Baru...

Untuk kegunaan lain, lihat Benggala (disambiguasi). Artikel ini mengandung aksara Bengali. Tanpa dukungan perenderan yang baik, Anda mungkin akan melihat tanda tanya, kotak, atau simbol lain. Benggala Zona berbahasa Benggala. Area di mana bahasa merupakan mayoritas. Area di mana bahasa merupakan minoritas. Teluk Benggala Benggala (bahasa Bengali: বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit. Bangla/Bôngô, diucapkan: [ˈbɔŋgo] simakⓘ) merupakan sebuah...

Coordinate: 49°57′52″N 8°12′29″E / 49.964444°N 8.208056°E49.964444; 8.208056 Zweites Deutsches FernsehenLogo dell'emittenteLogo di ZDFStato Germania Linguatedesco VersioniZDF (data di lancio: 1º aprile 1963) Nomi precedentiARD 2 (1961-1963) EditoreZweites Deutsches Fernsehen Sitozdf.de DiffusioneTerrestre Digitale ZDF (Germania)DVB-T - FTA Digitale ZDF (Bolzano)DVB-T - FTA Digitale ZDF (Trento)DVB-T - FTA Satellite Digitale Astra19.2° Est ZDF (DVB-S - FTA)11...

Medical imaging technique Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographyMRCP image showing stones in the distal common bile duct: (a) Gallbladder with stones, (b) Stones in bile duct, (c) Pancreatic duct, (d) Duodenum.ICD-9-CM88.97MeSHD049448OPS-301 code3-843[edit on Wikidata] Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a medical imaging technique. It uses magnetic resonance imaging to visualize the biliary and pancreatic ducts non-invasively. This procedure can be used to det...

Королевские гуркхские стрелкиангл. The Royal Gurkha Rifles Эмблема Королевских гуркхских стрелков Годы существования 1 июля 1994—н.в. Страна Великобритания Подчинение Британская армия Входит в Гуркхская бригада Тип пехота, стрелки Включает в себя два батальона лёгкой пехоты...

كرة اليد في الألعاب الأولمبية الصيفيةالهيئة الإداريةالاتحاد الدولي لكرة اليدالمنافسات2 (رجال: 1; سيدات: 1)الألعاب 1896 1900 1904 1908 1912 1920 1924 1928 1932 1936 1948 1952 1956 1960 1964 1968 1972 1976 1980 1984 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 2020 قائمة الفائزين بالميداليات بدأت منافسات كرة اليد في الألعاب الأولمبية الصيفية 1...

Giamaica Uniformi di gara Casa Trasferta Sport Calcio Federazione JFFJamaica Football Federation Confederazione CONCACAF Codice FIFA JAM Soprannome The Reggae Boyz (i ragazzi del Reggae) Selezionatore Heimir Hallgrímsson Record presenze Ian Goodison (128) Capocannoniere Luton Shelton (35) Ranking FIFA 55º (26 ottobre 2023)[1] Esordio internazionale Haiti 1 - 2 Giamaica Haiti; 9 marzo 1925 Migliore vittoria Giamaica 12 - 0 Isole Vergini Britanniche Grand Cayman, Isole Cayman; 4 marz...

تحتاج هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر إضافية لتحسين وثوقيتها. فضلاً ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة بإضافة استشهادات من مصادر موثوق بها. من الممكن التشكيك بالمعلومات غير المنسوبة إلى مصدر وإزالتها.Learn how and when to remove this message لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع هوية (توضيح).الهُوِيَّةُ هو مصطل...

رافائيل برسوناز (بالفرنسية: Raphaël Personnaz) معلومات شخصية الميلاد 23 يوليو 1981 (العمر 42 سنة)فرنسا مواطنة فرنسا الحياة العملية المدرسة الأم المعهد الوطني العالي للفنون الدرامية [لغات أخرى]مدرسة فلوران [لغات أخرى] المهنة ممثل، وممثل مسرحي، �...

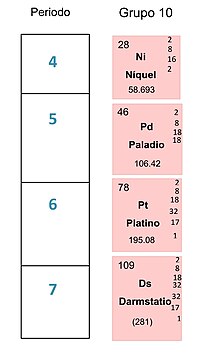

Los elementos que se pueden encontrar en el grupo 10 son los siguientes: Níquel (28) Paladio (46) Platino (78) Darmstatio (110) Estos elementos a temperatura ambiente se presentan en estado sólido. Grupo 10- Tabla periodica[1] Propiedades comunes También es conocida como la familia del níquel. Los estados de oxidación que tienen en común los elementos son 0 y +2. Todos se encuentran en la naturaleza en forma elemental aunque el níquel al ser el más reactivo de ellos, solamente ...

Series of events tied to two Miami television station sales Main article: Media in Miami Miami–Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach television network affiliate switches on January 1, 19891989 South Florida television affiliation switch at a glance Station Market Channel Affiliation(pre-1989) Affiliation(post-1989) WTVJ Miami–Fort Lauderdale 4 CBS NBC WCIX Miami–Fort Lauderdale 6 Fox CBS WSVN Miami–Fort Lauderdale 7 NBC Fox WPEC West Palm Beach 12 ABC CBS WPBF West Palm Beach 25 Not si...

Political party in Hungary Hungarian Civic Party redirects here. For the political party in Romania, see Hungarian Civic Party (Romania). For the former political party in Slovakia, see Hungarian Civic Party (Slovakia). Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Alliance Fidesz – Magyar Polgári SzövetségPresidentViktor OrbánVice presidents See list Kinga GálLajos KósaGábor KubatovSzilárd Németh Parliamentary leaderMáté KocsisFoundersViktor OrbánGábor FodorLászló KövérIstván BajkaiZsolt Ba...

Neolithic passage tomb located in the Boyne Valley, County Meath, Ireland This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Dowth – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) DowthDubhadhShown within IrelandLocationCounty Meath, IrelandCoordinates53°42�...

FaithfulAlbum studio karya Joy TobingDirilis2008Direkam2007-2008GenreReligiDurasi[[54:23]]LabelRhema Records dan SCTVProduserSunan HutabaratKronologi Joy Tobing Mujizat Itu Nyata(2006)Mujizat Itu Nyata2006 Faithful(2008) String Module Error: Match not foundString Module Error: Match not found Faithful adalah album religi Kristen ke dua yang dirilis tahun 2008 dari pemenang Indonesian Idol pertama, yaitu Joy Tobing. Album studio ke-empat milik Joy Joy Tobing ini melibatkan banyak musisi po...

American actress (born 1982) Lily RabeRabe in 2013Born (1982-06-29) June 29, 1982 (age 42)New York City, U.S.EducationNorthwestern University (BA)OccupationActressYears active2001–presentPartnerHamish Linklater (2013–present)Children3ParentsDavid RabeJill Clayburgh Lily Rabe (born June 29, 1982)[1][2] is an American actress. She is best known for her multiple roles on the FX anthology horror series American Horror Story (2011–2021). For her performance as Porti...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento unità militari non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. 9º Reggimento d'assalto paracadutisti "Col Moschin"Stemma del 9º Reggimento d'assalto paracadutisti Col Moschin Descrizione generaleAttivo1954 - oggi[1] Nazione Italia Servizio Eserc...

Frequency dependent circuit This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Audio filter – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Digital domain parametric equalisation An audio filter is a frequency-dependent circuit, working in the audio freq...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Tod. Tod InletGéographiePays CanadaProvince Colombie-BritanniqueDistrict régional district régional de la CapitaleAire protégée Parc provincial Gowlland Tod (en)Coordonnées 48° 33′ 44″ N, 123° 28′ 30″ OFonctionnementPatrimonialité Provincially Recognized Heritage Site (d) (2016)modifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata Tod Inlet est un grau du nord-ouest de la Colombie-Britannique. Géographie I...

この存命人物の記事には検証可能な出典が不足しています。 信頼できる情報源の提供に協力をお願いします。存命人物に関する出典の無い、もしくは不完全な情報に基づいた論争の材料、特に潜在的に中傷・誹謗・名誉毀損あるいは有害となるものはすぐに除去する必要があります。出典検索?: 飯伏幸太 – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii ...