Walter Bagehot

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Regata Oxford-CambridgeAltri nomiBoat Race Sport Canottaggio Paese Inghilterra LuogoLondra ImpiantoFiume Tamigi CadenzaAnnuale PartecipantiUniversità di CambridgeUniversità di Oxford Sito Internettheboatrace.org StoriaFondazione1829 Numero edizioni168 DetentoreCambridge Record vittorie86 Cambridge Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale La regata Oxford-Cambridge (in inglese semplicemente Boat Race) è una celebre gara di canottaggio. Si disputa annualmente sul fiume Tamigi, tra un e...

Sel satuan dari corundum Aluminium oksida (alumina) Aluminium oksida adalah sebuah senyawa kimia dari aluminium dan oksigen, dengan rumus kimia Al2O3. Nama mineralnya adalah alumina, dan dalam bidang pertambangan, keramik dan teknik material senyawa ini lebih banyak disebut dengan nama alumina. Sifat-sifat Aluminium oksida adalah insulator (penghambat) panas dan listrik yang baik. Umumnya Al2O3 terdapat dalam bentuk kristalin yang disebut corundum atau α-aluminum oksida. Al2O3 dipakai sebaga...

Action of the American Civil War This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Action at Blue Mills Landing – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Action at Blue Mills LandingPart of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of theAmerican Civ...

American politician (1899–1980) Page BelcherMember of the U.S. House of Representativesfrom OklahomaIn officeJanuary 3, 1951 – January 3, 1973Preceded byGeorge H. WilsonSucceeded byJames R. JonesConstituency8th district (1951–1953)1st district (1953–1973) Personal detailsBorn(1899-04-21)April 21, 1899Jefferson, Oklahoma TerritoryDiedAugust 2, 1980(1980-08-02) (aged 81)Midwest City, Oklahoma, U.S.Political partyRepublicanSpouseGladys CollinsAlma materUniversity of Okla...

العلاقات الغابونية الصربية الغابون صربيا الغابون صربيا تعديل مصدري - تعديل العلاقات الغابونية الصربية هي العلاقات الثنائية التي تجمع بين الغابون وصربيا.[1][2][3][4][5] مقارنة بين البلدين هذه مقارنة عامة ومرجعية للدولتين: وجه المقارنة الغ�...

Candi JagoNama sebagaimana tercantum dalamSistem Registrasi Nasional Cagar BudayaCandi Jago pada 2017. Cagar budaya IndonesiaPeringkatNasionalKategoriSitusNo. RegnasCB.445No. SKSK Menteri No. 177/M/1998Pemilik IndonesiaPengelolaBalai Pelestarian Cagar Budaya Jawa TimurKoordinat8°0′20.81″S 112°45′50.82″E / 8.0057806°S 112.7641167°E / -8.0057806; 112.7641167Candi JagoLokasi candi Jawi di kabupaten PasuruanTampilkan peta Surabaya dan MalangLokasi candi Ja...

1980 film by Robert Clouse The Big BrawlTheatrical release posterChinese nameTraditional Chinese殺手壕Simplified Chinese杀手壕TranscriptionsStandard MandarinHanyu Pinyinshāshǒu háoYue: CantoneseJyutpingsaat3 sau2 hou4 Directed byRobert ClouseWritten byRobert ClouseProduced byRaymond ChowFred WeintraubStarring Jackie Chan Kristine DeBell Mako Ron Max David Sheiner Rosalind Chao Lenny Montana Peter Marc José Ferrer CinematographyRobert C. JessupEdited byGeorge GrenvillePeter Cheu...

2018 ← 2019 → 2020素因数分解 3×673二進法 11111100011三進法 2202210四進法 133203五進法 31034六進法 13203七進法 5613八進法 3743十二進法 1203十六進法 7E3二十進法 50J二十四進法 3C3三十六進法 1K3ローマ数字 MMXIX漢数字 二千十九大字 弐千拾九算木 2019(二千十九、二〇一九、にせんじゅうきゅう)は、自然数また整数において、2018の次で2020の前の数である。 性質 2019は合成数で...

Opel AntaraInformasiProdusenOpelJuga disebutChevrolet Captiva SportDaewoo Winstorm MaXXGMC Terrain (Middle East)Holden Captiva 5Saturn VueVauxhall AntaraMasa produksi2006–sekarangPerakitanBupyeong, Korea Selatan (GM Korea)Ramos Arizpe, Mexico (GM México)St. Petersburg, Rusia (GM Auto)[1]Bodi & rangkaKelasSUV kompakBentuk kerangka5-pintu wagonTata letakMesin depan, penggerak roda depan/4WDPlatformTheta platformMobil terkaitSuzuki Grand VitaraChevrolet CaptivaChevrolet ...

Not to be confused with the drone delivery service Amazon Prime Air. Cargo airline Amazon Air (Prime Air)Founded2015; 9 years ago (2015)Hubs CincinnatiHyderabad[1] Leipzig/Halle[2]San Bernardino[3]Focus citiesFort Worth/AllianceMilan–MalpensaOntarioWilmington (OH)Fleet size90Parent companyAmazonKey peopleRaoul SreenivasanWebsiteamazon.com/airplanes Amazon Air (often branded as Prime Air) is a virtual cargo airline operating exclusively to transport ...

此條目介紹的是拉丁字母中的第2个字母。关于其他用法,请见「B (消歧义)」。 提示:此条目页的主题不是希腊字母Β、西里尔字母В、Б、Ъ、Ь或德语字母ẞ、ß。 BB b(见下)用法書寫系統拉丁字母英文字母ISO基本拉丁字母(英语:ISO basic Latin alphabet)类型全音素文字相关所属語言拉丁语读音方法 [b][p][ɓ](适应变体)Unicode编码U+0042, U+0062字母顺位2数值 2歷史發...

Series of battles in the Aegean For other uses, see Cretan War (disambiguation). Cretan WarGreece and the Aegean c. 201 BCDate205–200 BCLocationCrete, Rhodes, Greece, Asia Minor, and Aegean SeaResult Rhodian victoryTerritorialchanges Eastern Crete to RhodesBelligerents Macedonia, Hierapytna, Olous, Aetolia, Spartan pirates, Acarnania Rhodes, Pergamum, Byzantium, Cyzicus, Athens, KnossosCommanders and leaders Philip V, Dicaearchus, Nicanor the Elephant Attalus I,Theophiliscus †Cle...

Foster mother of Gautama Buddha and the first Buddhist nun Prajapati GautamiPrince Siddhartha with Mahaprajapati GautamiPersonalBornPrajāpatīDevdahaReligionBuddhismSpouseKing ŚuddhodanaChildren Sundari Nanda (daughter)Nanda (son) ParentsAñjana (father)Yashodhara (mother)OccupationBhikkhuni RelativesSuppabuddha (brother)Yashodhara (daughter in law)Maya Devi (sister) Senior postingTeacherGautama Buddha Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī (Pali; Sanskrit: महाप्रजापती गौतम�...

North American ethnic group PetunLanguagesPetun (Iroquoian)Related ethnic groupsWendat Indigenous peoplesin Canada First Nations Inuit Métis History Timeline Paleo-Indians Pre-colonization Genetics Residential schools gravesites Indian hospitals Conflicts First Nations Inuit Truth and Reconciliation Commission Politics Indigenous law British Columbia Treaty Process Crown and Indigenous peoples Health Policy Idle No More Indian Act Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada Land Back Land claims ...

This article is about the Thai chivalric order. For the Danish chivalric order, see Order of the Elephant. Thai award The Most Exalted Order of the White Elephantเครื่องราชอิสริยาภรณ์อันเป็นที่เชิดชูยิ่งช้างเผือก Knight Grand Cordon (Special Class) of the Most Exalted Order of the White ElephantAwarded by the King of ThailandTypeMilitary and Civilian OrderEstablished1861EligibilityRoyal officia...

Tetrakosana Nama Nama IUPAC (preferensi) Tetrakosana[1] Penanda Nomor CAS 646-31-1 Y Model 3D (JSmol) Gambar interaktif 3DMet {{{3DMet}}} Referensi Beilstein 1758462 ChEBI CHEBI:32936 Y ChemSpider 12072 Y Nomor EC PubChem CID 12592 Nomor RTECS {{{value}}} UNII YQ5H1M1D7I Y CompTox Dashboard (EPA) DTXSID8060955 InChI InChI=1S/C24H50/c1-3-5-7-9-11-13-15-17-19-21-23-24-22-20-18-16-14-12-10-8-6-4-2/h3-24H2,1-2H3 YKey: POOSGDOYLQNASK-UHFFFAOYSA-N Y SMILE...

Марек Повна назва Футбольний клуб «Марек» Прізвисько дупничани Засновано 1947 Населений пункт Дупниця, Болгарія Стадіон Бончук Вміщує 16 000 Головний тренер Янек Кючуков Ліга Південно-західна третя ліга 2016/17 8-е Домашня Виїзна ФК «Марек» Дупниця (болг. ФК Марек (Дупница))&#...

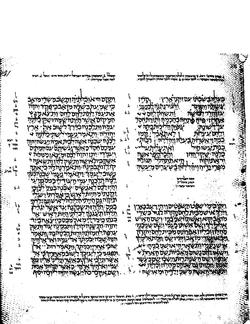

Alkitab IbraniTanakhYosua 1:1 pada Kodeks Aleppo Taurat (Pengajaran)KejadianBeresyitKeluaranSyemotImamatWaiyiqraBilanganBemidbarUlanganDevarim Nevi'im (Nabi-nabi) Awal YosuaYehosyuaHakim-hakimSyofetimSamuelSyemu'elRaja-rajaMelakhim Akhir YesayaYesyayahuYeremiaYirmeyahuYehezkielYekhezqelDua Belas NabiTrei Asar Ketuvim (Karya tulis) Puisi MazmurTehillimAmsalMisyleiAyubIyov Lima Gulungan(Hamesy Megillot) Kidung AgungSyir HassyirimRutRutRatapanEikhahPengkhotbahQoheletEsterEster ...

Large arid region in India and Pakistan Thar DesertGreat Indian DesertThar Desert in Rajasthan, IndiaMap of the Thar Desert ecoregionEcologyRealmIndomalayanBiomeDeserts and xeric shrublandsBordersNorthwestern thorn scrub forestsRann of Kutch seasonal salt marshGeographyArea238,254 km2 (91,990 sq mi)CountriesIndiaPakistanStates of India and provinces of PakistanIndia: RajasthanGujaratHaryanaPunjabPakistan: PunjabSindhCoordinates27°N 71°E / 27°N 71°E /...

Senat KremlinСенатский дворец Senatskiy DvoretsLetak di dalam Kremlin MoskwaInformasi umumGaya arsitekturNeoklasikKoordinat55°45′12″N 37°37′9″E / 55.75333°N 37.61917°E / 55.75333; 37.61917Penyewa sekarangAdministrasi kepresidenan RusiaMulai dibangun1776Rampung1788Desain dan konstruksiArsitekMatvey Kazakov. Senat Kremlin (bahasa Rusia: Сенатский дворец ; Senatskiy Dvorets) adalah sebuah gedung dalam kompleks Kremlin Mos...