Marisol Touraine

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Hiroshi Kiyotake Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Hiroshi KiyotakeTanggal lahir 12 November 1989 (umur 34)Tempat lahir Ōita, JepangTinggi 1,72 m (5 ft 7+1⁄2 in)Posisi bermain GelandangInformasi klubKlub saat ini Hannover 96Nomor 28Karier junior2002–2007 Oita TrinitaKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2008–2009 Oita Trinita 31 (4)2010–2012 Cerezo Osaka 66 (13)2012–2014 1. FC Nürnberg 64 (7)2014– Hannover 96 24 (4)Tim nasional‡2009 Jepang U-20 5 (1)2011– ...

Heros Paduppai Kepala Badan Instalasi Strategis Pertahanan[a]Masa jabatan11 Oktober 2016 – 10 April 2018MenteriRyamizard Ryacudu PendahuluParyantoPenggantiAlfred BH Rante Tandung Informasi pribadiLahir22 Januari 1960 (umur 64)Makassar, Sulawesi Selatan, IndonesiaPartai politikPKSSuami/istriNy. AisyahAnak1. Muhammad Herdiansyah2. Muhammad Hermawan3. Muhammad Rafie HKarier militerPihak IndonesiaDinas/cabang TNI Angkatan DaratMasa dinas1983—2018Pangkat Mayor J...

American comic book series published by DC ComicsGotham City SirensCover of Gotham City Sirens #1 (August 2009), art by Guillem March.Publication informationPublisherDC ComicsScheduleMonthlyFormatFinishedPublication dateJune 2009 – August 2011No. of issues26Main character(s)CatwomanHarley QuinnPoison IvyCreative teamCreated byPaul DiniGuillem MarchWritten byPaul Dini (#1, 2, 4–7, 9–11)Tony Bedard (#12–15)Peter Calloway (#16–26)Artist(s)Guillem March (#1–6, 8–9)Dav...

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Кузнечик (значения). КузнечикКузнечикъ Жанр стихотворение Автор Велимир Хлебников Язык оригинала русский Дата написания 1908 или 1909 Дата первой публикации 1912 Текст произведения в Викитеке «Кузне́чик» («Крылышкуя золотопи�...

Artistic syncretism between Classical Greece and Buddhist India Gandhara artTop: Standing Buddha from Gandhara, 1st-2nd century AD Centre:The Bimaran casket, representing the Buddha, is dated to around 30–10 BC. British Museum; Bottom: The Bodhisattva Maitreya, 2nd century AD, GandharaYears active1st century B.C. -5th century A.D. The Greco-Buddhist art or Gandhara art is the artistic manifestation of Greco-Buddhism, a cultural syncretism between Ancient Greek art and Buddhism. It had mainl...

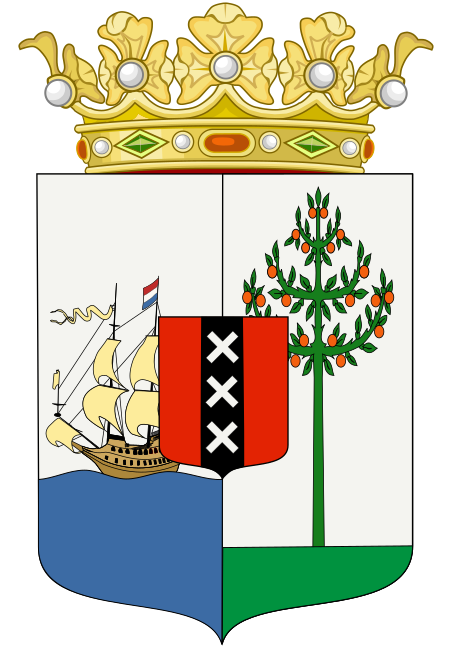

Politics of Curaçao Constitution Governor Lucille George-Wout Prime Minister Gilmar Pisas Cabinet Parliament Political parties Elections: 2010, 2012, 2016, 2017, 2021 Referendums: 1993, 2005, 2009 Other countries vte General elections were held in Curaçao on 19 October 2012.[1] Early elections for the Curaçao island council were necessary as the Cabinet-Schotte lost its majority in the Estates of Curaçao. The elections were the first of the Curaçao after obtaining the status of c...

England international footballer Alan Devonshire Devonshire in 2011Personal informationFull name Alan Ernest Devonshire[1]Date of birth (1956-04-13) 13 April 1956 (age 68)Place of birth Park Royal, EnglandHeight 5 ft 11 in (1.80 m)[2]Position(s) MidfielderTeam informationCurrent team Maidenhead United (manager)Youth career Crystal PalaceSenior career*Years Team Apps (Gls)0000–1976 Southall 1976–1990 West Ham United 358 (29)1990–1992 Watford 25 (1)Tota...

Resolusi 989Dewan Keamanan PBBGedung ICTR di KigaliTanggal24 April 1995Sidang no.3.524KodeS/RES/989 (Dokumen)TopikRwandaRingkasan hasil15 mendukungTidak ada menentangTidak ada abstainHasilDiadopsiKomposisi Dewan KeamananAnggota tetap Tiongkok Prancis Rusia Britania Raya Amerika SerikatAnggota tidak tetap Argentina Botswana Republik Ceko Jerman Honduras Indonesia Italia Nigeria Oman Rwanda Resolusi 989 Dewan K...

U.S. cricket organization This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources.Find sources: Major League Cricket 2000 – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2023) For the current cricket competition sanctioned by USA Cricket, see Major League Cricket. Major League CricketSportCricketFounded2000Ceas...

Indian film and television actress Not to be confused with Ambika Mohan or Ambika Sukumaran. AmbikaAmbika in 2014BornKallara, Thiruvananthapuram , Kerala, IndiaYears active1976–1989 (as a leading actress) 1997–present (as a supporting artist)Spouses Premkumar (m. 1988; div. 1996) Ravikanth (m. 2000; div. 2002) ChildrenRamkesav (b.1989)Rishikesh (b.1991)Parent(s)Kallara Kunjan Nair ...

إن حيادية وصحة هذه المقالة محلُّ خلافٍ. ناقش هذه المسألة في صفحة نقاش المقالة، ولا تُزِل هذا القالب من غير توافقٍ على ذلك. (نقاش) (يوليو 2018) يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن �...

Flag used by the People's Liberation Army, China Chinese People's Liberation ArmyUseWar flag and Naval jack Proportion4:5Adopted15 June 1949DesignA Chinese red field with a yellow star at the canton, and the Chinese numerals for 8 and 1, the date of the PLA's establishment on August 1, 1927. PLA flag during Nixon's visit to China The flag of the Chinese People's Liberation Army is the war flag of the People's Liberation Army; the layout of the flag has a golden star at the top left corner and...

Monument in Salisbury, North Carolina FameFame, Salisbury (location from 1909 to 2020)35°40′12.75″N 80°27′46.56″W / 35.6702083°N 80.4629333°W / 35.6702083; -80.4629333LocationSalisbury, North Carolina, U.S.TypeConfederate MonumentCompletion date1891 Fame, also called Gloria Victis (Glory to the Defeated or Glory to the Conquered),[1] is a Confederate monument in Salisbury, North Carolina. Cast in Brussels, in 1891, Fame is one of two nearly-ide...

Provincial electoral district in Manitoba, Canada Red River North Manitoba electoral districtProvincial electoral districtLegislatureLegislative Assembly of ManitobaMLA Jeff WhartonProgressive ConservativeDistrict created2018First contested2019Last contested2023DemographicsPopulation (2016)[1]21,000Electors (2019)15,077Area (km²)922Pop. density (per km²)22.8Census division(s)Division No. 12, Division No. 13, Division No. 19Census subdivision(s)Brokenhead 4, Divisio...

Фридрихсгамский мирный договор Тип договора Международный договор Дата подписания 5 (17) сентября 1809 года Место подписания Фридрихсгам, Выборгская губерния, Российская империя Вступление в силу 1 (13) октября 1809 года Подписали Николай Петрович Румянцев, ...

Paolo BloraNazionalità Italia Motociclismo CarrieraCarriera in SuperbikeEsordio1998 Miglior risultato finale41º Gare disputate39 Punti ottenuti11 Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Paolo Blora (Pavia, 12 ottobre 1969) è un pilota motociclistico italiano, ritiratosi dall'attività agonistica, campione italiano Superbike nel 1998, tecnico della specialità velocità del Gruppo Sportivo Fiamme Oro e responsabile tecnico di numerosi piloti impegnati nel motomondiale[1 ...

German mathematician Bernold FiedlerFiedler at Oberwolfach, 2008Born (1956-05-15) 15 May 1956 (age 68)NationalityGermanAlma materHeidelberg UniversityScientific careerFieldsMathematicsInstitutionsFree University of BerlinThesisStabilitätswechsel und globale Hopf-Verzweigung (1982)Doctoral advisorWilli JägerDoctoral studentsBjörn SandstedeArnd Scheel Bernold Fiedler (born 15 May 1956) is a German mathematician, specializing in nonlinear dynamics. Fiedler received a Diploma fr...

Realistic artificially generated media A video deepfake of Kim Jong Un created in 2020 by a nonpartisan advocacy group RepresentUs Part of a series onArtificial intelligence Major goals Artificial general intelligence Intelligent agent Recursive self-improvement Planning Computer vision General game playing Knowledge reasoning Natural language processing Robotics AI safety Approaches Machine learning Symbolic Deep learning Bayesian networks Evolutionary algorithms Hybrid intelligent systems S...

جيل شلهوب معلومات شخصية تاريخ الميلاد 9 يونيو 1983 (العمر 41 سنة) مواطنة لبنان الحياة العملية المهنة ممثل، ممثل صوت اللغات العربية المواقع IMDB صفحته على IMDB تعديل مصدري - تعديل جيل يوسف (9 يونيو 1983 - ) ممثل وممثل صوت لبناني.[1][2] فيلموغرافيا أفلام قميص الصوف - أم...

Daken AkihiroDisegni di Gabriele Dell'Otto UniversoUniverso Marvel Lingua orig.Inglese AutoriDaniel Way Steve Dillon EditoreMarvel Comics 1ª app.marzo 2007 1ª app. inWolverine: Origins n. 10 Editore it.Panini Comics - Marvel Italia 1ª app. it.novembre 2007 1ª app. it. inWolverine n. 214 Caratteristiche immaginarieAlter egoWolverine II SessoMaschio Poteri Fattore rigenerante Forza, agilità e riflessi sovrumani Sensi ipersviluppati Artigli ossei protrattili Emissione e...