Mario Puzo

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Dwi Soetjipto Kepala Satuan Kerja Khusus Pelaksana Kegiatan Usaha Hulu Minyak dan Gas BumiPetahanaMulai menjabat 3 Desember 2018 PendahuluAmien SunaryadiPenggantiPetahanaDirektur Utama PT Pertamina (Persero)Masa jabatan28 November 2014 – 3 Februari 2017 PendahuluKaren AgustiawanPenggantiElia Massa ManikDirektur Utama PT Semen IndonesiaMasa jabatan2010–2014 PenggantiSuparni Informasi pribadiLahir10 November 1955 (umur 68) Surabaya, Jawa Timur, IndonesiaSuami/istriHandiniA...

Strada statale 144di OropaDenominazioni successiveStrada provinciale 144 di Oropa LocalizzazioneStato Italia Regioni Piemonte DatiClassificazioneStrada statale InizioBiella FineSantuario di Oropa Lunghezza11,355[1] km Data aperturaD.P.R. 11 aprile 1951, n. 459[2] GestoreTratte ANAS: nessuna (dal 2001 la gestione è passata alla Provincia di Biella) Manuale Pietra miliare a Cossila La ex strada statale 144 di Oropa (SS 144), ora strada provinciale 144 di Oropa (SP 144...

President of Mexico from 1876 to 1877 For the municipality, see Juan N. Méndez (municipality). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Juan N. Méndez – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) In this Spanish name, the first or ...

Ukrainian tennis player Viktoriya KutuzovaCountry (sports) UkraineResidenceOdesa, UkraineBorn (1988-08-19) 19 August 1988 (age 35)Odesa, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet UnionHeight1.69 m (5 ft 7 in)Turned pro2003Retired2014PlaysRight (two-handed backhand)Prize money$586,580SinglesCareer record190–135 (58.5%)Career titles6 ITFHighest rankingNo. 76 (28 November 2005)Grand Slam singles resultsAustralian Open1R (2006, 2009, 2010)French Open2R (2...

Air warfare branch of Tanzania's military Tanzania Air Force CommandJeshi la Anga lA TanzaniaRoundel of the Tanzania Air Force CommandFounded2024; 0 years ago (2024)Country TanzaniaRoleAerial warfarePart ofTanzania People's Defence ForceEngagementsUganda–Tanzania WarCommandersCommanderMajor General Shaban ManiAircraft flownFighterChengdu F-7, Shenyang F-6HelicopterBell 412, Airbus H125, Airbus H155, Airbus H225LP,TrainerK-8 Karakorum, Shenyang FT-6, Chengdu FT-7T...

Luís Boa Morte Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Luís Boa Morte PereiraTanggal lahir 4 Agustus 1977 (umur 46)Tempat lahir Lisboa, PortugalTinggi 1,78 m (5 ft 10 in)[1]Posisi bermain GelandangInformasi klubKlub saat ini Sintrense (Manager)Nomor 72Karier junior1994–1996 Sporting CPKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)1997–1999 Arsenal 25 (0)1999–2001 Southampton 14 (2)2000–2001 → Fulham (loan) 39 (18)2001–2007 Fulham 156 (27)2007–2011 West Ham United 91 (...

Voce principale: Calcio Como. Calcio ComoStagione 2014-2015Sport calcio Squadra Como Allenatore Giovanni Colella, poi Carlo Sabatini All. in seconda Moreno Greco Presidente Pietro Porro Lega Pro4º nel girone A, promosso in Serie B dopo i play-off Coppa ItaliaTerzo turno Coppa Italia Lega ProFinalista Maggiori presenzeCampionato: Le Noci (38)Totale: Le Noci (49) Miglior marcatoreCampionato: Ganz, Le Noci (11)Totale: Ganz (18) Abbonati739[1] Maggior numero di spettatori6 143 vs B...

Bagian dari seri tentangBuddhisme Awal Teks Buddhis Teks Buddhis Awal Bhāṇaka Tipiṭaka Nikāya Āgama Teks Buddhis Gandhāra Jataka Avadana Abhidharma Sidang Buddhis Pertama Kedua Ketiga Keempat Buddhisme Awal Buddhisme prasektarian → Aliran Buddhis awal Mahāsāṃghika Ekavyāvahārika Lokottaravāda Gokulika Bahuśrutīya Prajñaptivāda Caitika (Haimavata) Sthavira nikāya (Sthaviravāda) Pudgalavāda Vātsīputrīya Saṃmitīya Sarvāstivāda (Haimavata) (Kāśyapīya) (Mahīśā...

Voce principale: Campionato mondiale di Formula 1 2000. Gran Premio della Malesia 2000 663º GP del Mondiale di Formula 1Gara 17 di 17 del Campionato 2000 Data 22 ottobre 2000 Luogo Circuito di Sepang Percorso 5,543 km Circuito permanente Distanza 56 giri, 310,408 km Clima Sereno Risultati Pole position Giro più veloce Michael Schumacher Mika Häkkinen Ferrari in 1'37397 McLaren - Mercedes in 1'38453 (nel giro 34) Podio 1. Michael SchumacherFerrari 2. David CoulthardMcLaren - Mercedes...

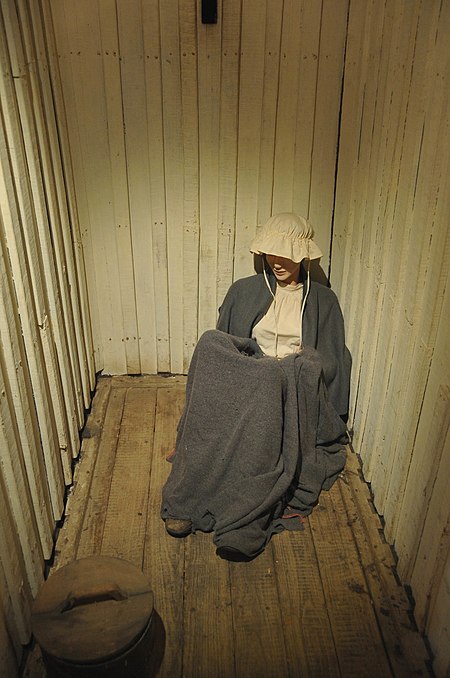

Tourist attraction in Tasmania This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Richmond Gaol – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Richmond GaolLocationRichmond, TasmaniaCoordinates42°44′11″S 147°26′20″E / 42.7364°S 1...

Азиатский барсук Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:СинапсидыКласс:Мле�...

Франц Саксен-Кобург-Заальфельдскийнем. Franz von Sachsen-Coburg-Saalfeld герцог Саксен-Кобург-Заальфельдский 8 сентября 1800 — 9 декабря 1806 Предшественник Эрнст Фридрих Саксен-Кобург-Заальфельдский Преемник Эрнст I Саксен-Кобург-Заальфельдский Рождение 15 июля 1750(1750-07-15)Кобург, Сакс...

2016年美國總統選舉 ← 2012 2016年11月8日 2020 → 538個選舉人團席位獲勝需270票民意調查投票率55.7%[1][2] ▲ 0.8 % 获提名人 唐納·川普 希拉莉·克林頓 政党 共和黨 民主党 家鄉州 紐約州 紐約州 竞选搭档 迈克·彭斯 蒂姆·凱恩 选举人票 304[3][4][註 1] 227[5] 胜出州/省 30 + 緬-2 20 + DC 民選得票 62,984,828[6] 65,853,514[6]...

EquusPoster rilis teatrikalSutradaraSidney LumetProduserElliott KastnerLester PerskyDenis HoltSkenarioPeter ShafferBerdasarkanEquusoleh Peter ShafferPemeranRichard BurtonPeter FirthJenny AgutterJoan PlowrightColin BlakelyPenata musikRichard Rodney BennettSinematograferOswald MorrisPenyuntingJohn Victor-SmithPerusahaanproduksiWinkast Film ProductionsDistributorUnited ArtistsTanggal rilis 14 Oktober 1977 (1977-10-14) (Britania Raya) 16 Oktober 1977 (1977-10-16) (Amerika ...

2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会波兰代表團波兰国旗IOC編碼POLNOC波蘭奧林匹克委員會網站olimpijski.pl(英文)(波兰文)2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会(東京)2021年7月23日至8月8日(受2019冠状病毒病疫情影响推迟,但仍保留原定名称)運動員206參賽項目24个大项旗手开幕式:帕维尔·科热尼奥夫斯基(游泳)和马娅·沃什乔夫斯卡(自行车)[1]闭幕式:卡罗利娜·纳亚(皮划艇)&#...

هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالات أخرى قليلة جدًا. فضلًا، ساعد بإضافة وصلة إليها في مقالات متعلقة بها. (أكتوبر 2020) نادي الروضة موسم 2019–20 الرئيس الهيئة العامة للرياضة الملعب ملعب الأمير عبد الله بن جلوي دوري الدرجة الثانية السعودي المركز السابع كأس خادم الحرمين الشريفي�...

American record label For the label founded in the 1950s by George Goldner, see End Records. The End RecordsParent companyBMG Rights ManagementFounded1998 (1998)FounderAndreas Katsambas[1]Distributor(s)Universal Music Group[2]GenreRock, heavy metal, experimental, indie rockCountry of originUnited StatesLocationNew York CityOfficial websitewww.theendrecords.com The End Records is a record label in Manhattan that specializes in rock, heavy metal, indie, and electronic music...

Timeline of piracy in the 1990s This timeline of piracy in the 1990s is a chronological list of key events involving pirates between 1990 and 1999. Events 1995 September 13 - The freighter Anna Sierra is boarded off the coast of Thailand after a group numbering 30 men overtook the ship in a motorboat. Heavily armed, the crew were forced to surrender and eventually set adrift in the ship's lifeboats. The pirates set sail for China and, repainting and refitting the ship within two day...

アイザック・バシェヴィス・シンガー 誕生 (1903-11-11) 1903年11月11日 ロシア帝国(現 ポーランド) ラジミン死没 1991年7月24日(1991-07-24)(87歳没) アメリカ合衆国フロリダ州マイアミ職業 作家言語 イディッシュ語民族 ポーランド系ユダヤ人市民権 アメリカ合衆国ジャンル 散文主な受賞歴 ノーベル文学賞(1978) ウィキポータル 文学テンプレートを表示 ノーベル賞受賞者 受...

Colin Hanks al South by Southwest 2015 Colin Lewes Hanks (Sacramento, 24 novembre 1977) è un attore statunitense. Indice 1 Biografia 1.1 Carriera 1.2 Vita privata 2 Filmografia 2.1 Cinema 2.2 Televisione 3 Doppiaggio 4 Doppiatori italiani 5 Altri progetti 6 Collegamenti esterni Biografia Nato dal primo matrimonio dell'attore Tom Hanks (finito con un divorzio quando aveva 10 anni) con l'attrice Samantha Lewes, morta per un cancro alle ossa nel 2002, ha una sorella, Elizabeth (nata nel 1982), ...