Joseon Tongbo

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Irisosaurus Periode Jura Awal, Hettangian PreЄ Є O S D C P T J K Pg N ↓ Restorasi kerangkaTaksonomiKerajaanAnimaliaFilumChordataKelasReptiliaOrdoSaurischiaGenusIrisosaurus lbs Irisosaurus adalah sebuah genus punah dari dinosaurus sauropodomorfa Sauropodiformes,[1] dari Formasi Fengjiahe di Tiongkok. Spesies tipenya, Irisosaurus yimenensis secara resmi dideskripsikan pada 2020.[1][2] Genus tersebut adalah takson saudara dari Mussaurus. Referensi ^ a b Claire Pey...

Biografi ini tidak memiliki sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak dapat dipastikan. Bantu memperbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan sumber tepercaya. Materi kontroversial atau trivial yang sumbernya tidak memadai atau tidak bisa dipercaya harus segera dihapus.Cari sumber: Al-Mu'tashim Billah – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR (Pelajari cara dan kapan saatnya untuk menghapus pesan templat ini) Biografi ini memerlukan lebih banyak cata...

Australian architect E.C. ManfredBorn5 June 1856Kensington, LondonDied20 February 1941 (aged 84)Goulburn, New South WalesNationalityAustralianOccupationArchitectBuildingsSt. John's Orphanage (1912)St. Joseph's Orphanage (1905) Edmund Cooper Manfred (5 June 1856 – 20 February 1941)[1] often referred as E.C. Manfred was an English born Australian architect who was prominent for his works for designing well known and iconic buildings in Goulburn, New South Wales.[2] Early life ...

Labeling systems for food and consumer products Green label redirects here. For the online magazine, see Green Label. Classification of eco-labels Ecolabels (also Eco-Labels) and Green Stickers are labeling systems for food and consumer products. The use of ecolabels is voluntary, whereas green stickers are mandated by law; for example, in North America major appliances and automobiles use Energy Star. They are a form of sustainability measurement directed at consumers, intended to make it ea...

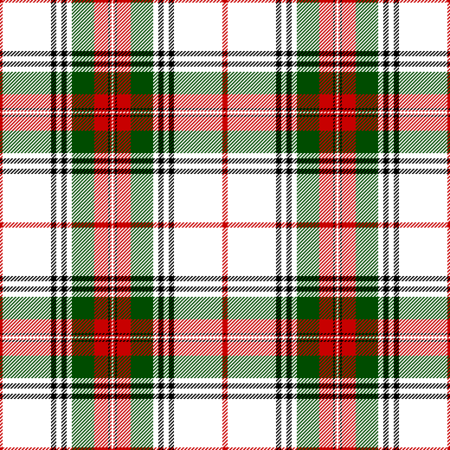

List of tartan patterns This is a list of tartans from around the world. The examples shown below are generally emblematic of a particular association. However, for each clan or family, there are often numerous other official or unofficial variations. There are also innumerable tartan designs that are not affiliated with any group but were simply created for aesthetic reasons (and which are not within the scope of this list). British royal and noble tartans Tartans in this section are those t...

Artikel ini perlu diterjemahkan ke bahasa Indonesia. Artikel ini ditulis atau diterjemahkan secara buruk dari Wikipedia bahasa selain Indonesia. Jika halaman ini ditujukan untuk komunitas berbahasa tersebut, halaman itu harus dikontribusikan ke Wikipedia bahasa tersebut. Lihat daftar bahasa Wikipedia. Artikel yang tidak diterjemahkan dapat dihapus secara cepat sesuai kriteria A2. Jika Anda ingin memeriksa artikel ini, Anda boleh menggunakan mesin penerjemah. Namun ingat, mohon tidak menyalin ...

Rosa ParksRosa Parks pada tahun 1955, dengan Martin Luther King, Jr. dalam latar belakang.LahirRosa Louise McCauley(1913-02-04)4 Februari 1913Tuskegee, Alabama, Amerika SerikatMeninggal24 Oktober 2005(2005-10-24) (umur 92)Detroit, Michigan, Amerika SerikatKebangsaanAmerikaPekerjaanAktivis hak-hak sipilDikenal atasMontgomery Bus BoycottKota asalTuskegee, AlabamaSuami/istriRaymond Parks (1932–1977; bercerai)Tanda tangan Rosa Parks (lahir di Tuskegee, Alabama 4 Februari 1913 �...

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Sustainable Energy for All – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Sustainable Energy for AllAbbreviationSEforALLFormation2011; 13 years ago (2011) as UN Sustainable Energy for A...

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع خلف الأبواب المغلقة (توضيح). هذه المقالة بحاجة لصندوق معلومات. فضلًا ساعد في تحسين هذه المقالة بإضافة صندوق معلومات مخصص إليها. يستخدم مصطلح خلف الأبواب المغلقة (بالإنجليزية: Behind closed doors) في العديد من الألعاب الرياضية، خاصة في كرة القدم،[1] لوصف ا�...

Disambiguazione – Se stai cercando altri significati, vedi Campionato mondiale costruttori. Il campionato mondiale costruttori di Formula 1 (in inglese Formula One World Constructors' Championship, abbreviato WCC) viene attribuito ufficialmente dalla Federazione Internazionale dell'Automobile ed è determinato da un particolare sistema di punteggio, che nel corso degli anni è variato, basato sui risultati ottenuti in ogni Gran Premio. Indice 1 Criterio 2 Statistiche 3 Albo d'oro 3.1 Per s...

Untuk orang lain dengan nama yang sama, lihat Bjarni Benediktsson. Bjarni Benediktsson Perdana Menteri Islandia ke-13Masa jabatan14 November 1963 – 10 Juli 1970PresidenÁsgeir ÁsgeirssonKristján EldjárnPendahuluÓlafur ThorsPenggantiJóhann HafsteinMasa jabatan8 September 1961 – 31 Desember 1961PresidenÁsgeir ÁsgeirssonPendahuluÓlafur ThorsPenggantiÓlafur Thors Informasi pribadiLahir(1908-04-30)30 April 1908Reykjavík, IslandiaMeninggal10 Juli 1970(1970-07-10) (um...

Container for holding water for animals to drink from For water trough, a device that enables a steam railway locomotive to replenish its water supply while in motion, see Water trough. A watering trough on a stock route, Australia A Bills horse trough in Sebastian, Victoria, Australia Sheep watering trough, Idaho, 1930s A watering trough (or artificial watering point) is a man-made or natural receptacle intended to provide drinking water to animals, livestock on farms or ranches or wild anim...

San JoaquinStato Stati Uniti Stati federati California Lunghezza530 km Bacino idrografico83 000 km² Altitudine sorgente3 354 m s.l.m. SfociaBaia di San Francisco Mappa del fiume Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Il San Joaquin è un fiume che corre per 530 km nello Stato della California, negli Stati Uniti occidentali. Nasce nella Sierra Nevada e sfocia nella baia di San Francisco, formando un delta con il fiume Sacramento. È il secondo fiume della Californi...

Richard DonnerLahirRichard Donald Schwartzberg(1930-04-24)24 April 1930Bronx, Kota New York, A.S.Meninggal5 Juli 2021(2021-07-05) (umur 91)PekerjaanSutradara film, sutradara televisi, produser filmTahun aktif1957–2009Karya terkenal The Omen Superman The Goonies Lethal Weapon Scrooged Maverick Superman II: The Richard Donner Cut Suami/istriLauren Shuler Donner (m. 1985; wafat 2021) Richard Donner (nama lahir Richard Donald Schwar...

Historic church in New Jersey, United States United States historic placeSix Mile Run Reformed ChurchU.S. National Register of Historic PlacesNew Jersey Register of Historic Places Six Mile Run Reformed Church and Chapel in 2022Show map of Somerset County, New JerseyShow map of New JerseyShow map of the United StatesLocation3037 New Jersey Route 27Franklin Park, New JerseyCoordinates40°26′19″N 74°32′10″W / 40.43861°N 74.53611°W / 40.43861; -74.53611Built187...

Austrian footballer Christoph Monschein Monschein in 2016Personal informationDate of birth (1992-10-22) 22 October 1992 (age 31)Place of birth Brunn am Gebirge, Austria[1]Height 1.78 m (5 ft 10 in)Position(s) StrikerTeam informationCurrent team First ViennaNumber 7Youth career1998–2009 SC Brunn am GebirgeSenior career*Years Team Apps (Gls)2009–2014 SC Brunn am Gebirge 117 (42)2014–2016 ASK Ebreichsdorf 45 (35)2016–2017 Admira Wacker 39 (12)2017–2021 Austr...

Gereja di Tara Eparki Tara adalah sebuah eparki Gereja Ortodoks Rusia yang terletak di Tara, Federasi Rusia. Eparki tersebut didirikan pada tahun 2012.[1] Referensi ^ http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/2270689.html lbsKeuskupan Gereja Ortodoks RusiaPatriark MoskwaEparki di Rusia Abakan dan Khakassia Akhtubinsk Alapayevsk Alatyr Alexdanrov Almetyevsk Amur Anadyr Ardatov Arkhangelsk Armavir Arsenyev Astrakhan Balashov Barnaul Barysh Belgorod Belyov Bezhetsk Birobidzhan Birsk Biysk Blagov...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant la presse écrite. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Pour les articles homonymes, voir dpa. Deutsche Presse-Agentur Création 1949 Forme juridique GmbH Siège social Hambourg Allemagne Directeurs Sven Gösmann (d) (depuis 2014) Actionnaires Westdeutscher Rundfunk (3,9 %)[1]Deutsche Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft (d) (1,3 %)[1]Axel Springer Verl...

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع سنترفيل (توضيح). سنترفيل الإحداثيات 31°15′23″N 95°58′46″W / 31.256388888889°N 95.979444444444°W / 31.256388888889; -95.979444444444 [1] تقسيم إداري البلد الولايات المتحدة[2][3] التقسيم الأعلى مقاطعة ليون عاصمة لـ مقاطعة ليون خصائص جغرافي...

نورثامبرلاند الإحداثيات 44°33′48″N 71°33′31″W / 44.563333333333°N 71.558611111111°W / 44.563333333333; -71.558611111111 [1] تاريخ التأسيس 1767 تقسيم إداري البلد الولايات المتحدة[2] التقسيم الأعلى مقاطعة كوس خصائص جغرافية المساحة 94.5 كيلومتر مربع ارتفاع 262 متر&...