Industrial violence

|

Read other articles:

Allotinus fallax Male Female Klasifikasi ilmiah Kerajaan: Animalia Filum: Arthropoda Kelas: Insecta Ordo: Lepidoptera Famili: Lycaenidae Genus: Allotinus Spesies: A. fallax Nama binomial Allotinus fallaxC. & R. Felder, [1865][1] Sinonim Allotinus fallax sabazus Fruhstorfer, 1913 Allotinus fallax zaradrus Fruhstorfer, 1915 Allotinus fallax ancius Fruhstorfer, 1913 Allotinus fallax artinus Fruhstorfer, 1916 Allotinus apus de Nicéville, 1895 Allotinus fallax michaelis Eliot, 1...

Nama ini menggunakan kebiasaan penamaan Filipina; nama tengah atau nama keluarga pihak ibunya adalah Bautista dan marga atau nama keluarga pihak ayahnya adalah Rodriguez. Rufus Rodriguez Anggota DPR dari dapil II Cagayan de OroPetahanaMulai menjabat 30 Juni 2019 PendahuluMaxie RodriguezPenggantiPetahanaMasa jabatan30 Juni 2007 – 30 Juni 2016 PendahuluConstantino G. JaraulaPenggantiMaxie Rodriguez Informasi pribadiLahirRufus Bautista Rodriguez13 September 1953 (umur 70...

Fachrori UmarFachrori Umar sebagai Gubernur Jambi (2019) Gubernur Jambi ke-9Masa jabatan13 Februari 2019 – 12 Februari 2021(Pelaksana Tugas: 10 April 2018 – 13 Februari 2019)WakilLowong PendahuluZumi ZolaPenggantiSudirman (Plh.)Hari Nur Cahya Murni (Pj.)Al HarisWakil Gubernur Jambi ke-5Masa jabatan12 Februari 2016 – 10 April 2018GubernurZumi Zola PenggantiAbdullah SaniMasa jabatan3 Agustus 2010 – 3 Agustus 2015GubernurHasan Basri Agus PendahuluAntony...

John WilliamsJohn Williams di Avery Fisher Hall, 2007Informasi latar belakangNama lahirJohn Towner WilliamsLahir8 Februari 1932 (umur 92)AsalFlushing, Queens, New York, Amerika SerikatGenreMusik film, musik klasik kontemporer, jazzPekerjaankomponis, pianis, konduktorTahun aktif1952–sekarang John Towner Williams (lahir 8 Februari 1932) merupakan seorang komposer, konduktor, pianis, dan produser rekaman musik asal Amerika Serikat. Kariernya saat ini telah menginjak usia enam decade. Will...

NYU Tisch School of the ArtsJenisPrivateDidirikan1965Staf akademik216Sarjana3.163Magister939LokasiKota New York, New York, Amerika SerikatDeanMary Schmidt CampbellSitus webTisch.NYU.edu Tisch School of the Arts (lebih dikenal dengan Tisch or TSOA) iadalah salah satu sekolah yang membuat New York University (NYU). Sekolah ini didirikan pada tahun 1965. Sekolah ini mempunyai 2700 orang sarjana (dalam 7 program) dan 500 siswa magister (dalam 10 programs). Tisch sering dikenal untuk program actin...

Untuk aktor dengan nama yang mirip, lihat Alec Baldwin. Adam BaldwinAdam BaldwinLahir27 Februari 1962 (umur 62)Winnetka, Illinois, U.S.PekerjaanAktorTahun aktif1980–sekarangSuami/istriAmi Julius (m. 1988)Anak3 Adam Baldwin (lahir 27 Februari 1962) adalah seorang aktor Amerika. Dia membintangi Full Metal Jacket (1987) sebagai Ibu Hewan, serta di serial televisi Firefly dan film lanjutannya Serenity sebagai Jayne Cobb. Perannya termasuk Stillman di Ord...

Rocket launching complex of the Plesetsk Cosmodrome in northwestern Russia Site 43Launch sitePlesetsk CosmodromeCoordinates62°55′12″N 40°28′1″E / 62.92000°N 40.46694°E / 62.92000; 40.46694Short namePu-43OperatorRussian Space ForcesTotal launches545Launch pad(s)TwoSite 43/3 launch historyStatusActiveLaunches223First launch21 December 1965R-7A SemyorkaLast launch27 October 2023Soyuz-2.1b / Lotos-S1 №7AssociatedrocketsR-7A Semyorka (retired)Vostok-...

1997 studio album by Earth, Wind & FireIn the Name of LoveStudio album by Earth, Wind & FireReleasedJuly 22, 1997Recorded1996StudioSony Music Studios, Los Angeles, Sunset Sound, HollywoodGenreR&B, soul, funkLength56:21LabelRhinoProducerMaurice WhiteEarth, Wind & Fire chronology Let's Groove: The Best of Earth, Wind & Fire(1996) In the Name of Love(1997) Greatest Hits(1998) Reissue cover2006 Reissue Cover Singles from In the Name of Love In the Name of LoveReleased:...

NASA rocket transport vehicle Motor vehicle Crawler-transporterOverviewManufacturerMarion Power Shovel CompanyAlso calledMissile Crawler Transporter FacilitiesModel years1965PowertrainEngine2 × 2,050 kW (2,750 hp) V16 ALCO 251C diesel engines, driving 4 × 1,000 kW (1,341 hp) generators for traction2 × 794 kW (1,065 hp) engines driving 2 × 750 kW (1,006 hp) generators powering auxiliaries: jacking, steering, lighting, and ventilating.Transm...

Lal JoseLahirValapad,thrissur, Kerala, IndiaTempat tinggalOttapalam, Kerala, IndiaNama lainLaluPekerjaanSutradara film, produser, distributorTahun aktif1989–sekarangSuami/istriLeena Lal Jose adalah sebuah sutradara film India dan produser yang paling dikenal karena film-film Malayalamnya. Lal Jose memulai karier filmnya sebagai asisten sutradara Kamal. Lal Jose bekerja padafilm-film Kamal pada 1990an. Debut penyutradaraannya adalah film Oru Maravathoor Kanavu (1998). Film-film po...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento centri abitati della Malaysia non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Kuala Lumpurterritorio federaleWilayah Persekutuan Kuala Lumpur Kuala Lumpur – Veduta LocalizzazioneStato Malaysia AmministrazioneMinistroMhd Amin Nordin Abdul Aziz dal 18-7-2015 TerritorioCoordinate3°08′51″N 101°41′36...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Bonnières et Seine (homonymie). Bonnières-sur-Seine La mairie. Blason Administration Pays France Région Île-de-France Département Yvelines Arrondissement Mantes-la-Jolie Intercommunalité Communauté de communes Les Portes de l'Ile de France Maire Mandat Jean-Marc Pommier 2020-2026 Code postal 78270 Code commune 78089 Démographie Populationmunicipale 5 038 hab. (2021 ) Densité 658 hab./km2 Population agglomération 14 602 hab....

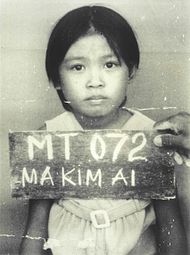

Questa voce sull'argomento diritto internazionale è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Una giovane vietnamita in un campo profughi in Malaysia (1980). Per rifugiato si intende generalmente una persona che si trova al di fuori del proprio paese di origine e che non può o non vuole tornarvi per fondati motivi di discriminazione politica, religiosa, razziale, di nazionalità o a causa di persecuzioni. Un rifugiato che ha formalmente presentat...

密西西比州 哥伦布城市綽號:Possum Town哥伦布位于密西西比州的位置坐标:33°30′06″N 88°24′54″W / 33.501666666667°N 88.415°W / 33.501666666667; -88.415国家 美國州密西西比州县朗兹县始建于1821年政府 • 市长罗伯特·史密斯 (民主党)面积 • 总计22.3 平方英里(57.8 平方公里) • 陸地21.4 平方英里(55.5 平方公里) • ...

此条目序言章节没有充分总结全文内容要点。 (2019年3月21日)请考虑扩充序言,清晰概述条目所有重點。请在条目的讨论页讨论此问题。 哈萨克斯坦總統哈薩克總統旗現任Қасым-Жомарт Кемелұлы Тоқаев卡瑟姆若马尔特·托卡耶夫自2019年3月20日在任任期7年首任努尔苏丹·纳扎尔巴耶夫设立1990年4月24日(哈薩克蘇維埃社會主義共和國總統) 哈萨克斯坦 哈萨克斯坦政府...

Protestant denomination in Japan The United Church of Christ in Japan日本基督教団Nihon Kirisuto KyōdanAbbreviationUCCJClassificationJapanese Independent ChurchAssociationsWorld Council of ChurchesChristian Conference of AsiaNational Council of Churches in JapanRegionJapanEleven other countriesOrigin24 June 1941 Fujimicho ChurchMerger ofThirty-three denominationsSeparationsAnglican Church in JapanJapan Assemblies of GodJapan Baptist ConventionJapan Holiness ChurchJapan Lutheran ChurchRe...

Großfürst Iwan IV. entsandte Theodoret nach Konstantinopel Theodoretos, Theodorit(es) bzw. Theodoret von Kola (* 1489[1] in Rostow, Großfürstentum Moskau; † 17. Augustjul./30. Augustgreg. 1571 im Solowezki-Kloster, Russland), russisch Feodorit[2] Kolski (Феодорит Кольский) war ein russischer Missionar des Solowezki-Klosters, weshalb er gelegentlich auch als Theodoret (von) Solowezki bezeichnet wird. Er gilt als Apostel der Lappen (Samen) und wird in Teile...

YalovaMunicipalityYalovaKoordinat: 40°39′20″N 29°16′30″E / 40.65556°N 29.27500°E / 40.65556; 29.27500CountryTurkeyProvinsiYalovaPemerintahan • MayorVefa Salman, CHPLuas[1] • District166,85 km2 (6,442 sq mi)Ketinggian30 m (100 ft)Populasi (2012)[2] • Perkotaan102.874 • District121.479 • Kepadatan District7,3/km2 (19/sq mi)Situs webwww.yalova.bel.tr ...

Эта статья — о крымском красном терроре в 1920—1921 годах. О событиях в Крыму в 1917—1918 годах см. Массовый террор в Крыму (1917—1918). См. также: Красный террор Кра́сный терро́р в Крыму́ — красный террор, проводившийся на территории Крымского полуострова в 1920—1921 года�...

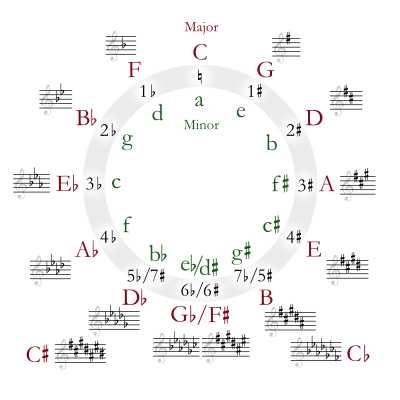

Set of musical alterations For use in cryptography, see Key signature (cryptography). Key signature showing B♭ and E♭ (the key of B♭ major or G minor) Key signature showing F♯ and C♯ (the key of D major or B minor) In Western musical notation, a key signature is a set of sharp (♯), flat (♭), or rarely, natural (♮) symbols placed on the staff at the beginning of a section of music. The initial key signature in a piece is placed immediatel...