Hiram Sanford Stevens

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Jean-Pierre Laurens in his studio (1931) Mother and Daughter Jean-Pierre Laurens (18 Maret 1875 – 23 April 1932) adalah seorang pelukis Prancis; terutama gambar dan potret. Biografi Dia adalah putra bungsu dari pelukis, Jean-Paul Laurens. Kakak laki-lakinya, Paul Albert Laurens juga menjadi seorang seniman,[1] dan dia menikah dengan pematung, Yvonne Diéterle. Ia belajar dengan Léon Bonnat di École des Beaux-Arts. Pameran pertamanya di Salon datang pada tahun 1899, k...

Mr. Monk Helps Himself First edition 2013 hard coverAuthorHy ConradCountryUnited StatesLanguageEnglishSeriesMonk mystery novel seriesGenreMystery novelPublisherSignet BooksPublication dateJune 4, 2013Media typePrint (hardcover)Preceded byMr. Monk Gets Even Followed byMr. Monk Gets on Board Mr. Monk Helps Himself is the sixteenth novel based on the television series Monk. It was published on June 4, 2013. Like the other novels, the story is narrated by Natalie Teeger,...

Serbian–French–American cinematographer Paul IvanoIvano (right) with camera assistants Robert Lazlo and Frank Heisler and Ella Raines on the set of The Suspect (1944)BornPaul Ivano-Ivanichevitch (Romanized Serbian)May 13, 1900 (1900-05-13)Nice, FranceDiedApril 9, 1984 (1984-04-10) (aged 83)Woodland Hills, CaliforniaOccupationCinematographerSpouseMargaret (Greta) Ginsburg Ivano[1][2] Paul Ivano, ASC (May 13, 1900 – April 9, 1984), was a Serbian–...

Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: Michael Jakarimilena – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR Michael JakarimilenaLahirMichael Herman Jakarimilena13 Juli 1983 (umur 40)Jayapura, IndonesiaPekerjaanaktor, penyanyiSuami/is...

Private social club in Pennsylvania, US Cosmopolitan Club of PhiladelphiaThe Cosmopolitan Club of PhiladelphiaTypeSocial clubTax ID no. 23-0495600Websitewww.cosclub.org The Cosmopolitan Club of Philadelphia is a private social club in Philadelphia. It was founded in June 1928 by a group of women from Philadelphia and its surroundings.[1] In January 1930, the members had purchased the lot at 1616 Latimer Street, and oversaw the construction of an Art Deco building.[1] The membe...

Area in Lagos Island Port at Olowogbowo Olowogbowo is an area in the west of Lagos Island in Lagos, also known as Apongbon. The area is in the central business district.[1] The community was founded after 1851, when freed Yoruba captives and their descendants who had been set ashore in Sierra Leone returned in successive waves to Lagos, and were granted land to settle in the Olowogbowo and Breadfruit areas of the island.[2] The name Apongbon is a garbled version of the Yoruba...

Questa voce sull'argomento poeti francesi è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Jean de La Taille Jean de La Taille (Bondaroy, 1540 – Parigi, 1607) è stato un poeta e drammaturgo francese. Indice 1 Biografia 2 Note 3 Bibliografia 4 Altri progetti 5 Collegamenti esterni Biografia Studiò discipline umanistiche a Parigi con Muretu e legge a Orléans con Anne de Bourg. Nella prima fase della sua carriera fu ugonotto, ma successivamente si co...

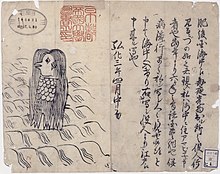

Ilustrasi sosok Amabie yang bersumber pada salah satu surat kabar (kawaraban) dari zaman Edo Amabie (アマビエ) adalah makhluk legenda dalam cerita rakyat Jepang berwujud putri duyung dengan mulut seperti paruh burung yang muncul dari laut. Ia bergerak menggunakan ketiga kaki atau siripnya dan diyakini dapat meramalkan panen berlimpah atau wabah. Amabie kemungkinan merupakan bentuk lain dari Amabiko atau Amahiko, atau dikenal juga sebagai Amahiko-nyūdo (尼彦入道). Sumber tertulis yang...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento calciatori italiani non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Questa voce sull'argomento calciatori italiani è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Gino Bonzi Nazi...

Questa voce sull'argomento stagioni delle società calcistiche italiane è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Voce principale: Ostiglia Football Club. Ostiglia Football ClubStagione 1923-1924Sport calcio Squadra Ostiglia Seconda Divisione7º posto nel girone D della Seconda Divisione, retrocessa in Terza Divisione 1922-1923 1924-1925 Si invita a seguire il modello di voce Questa pagina r...

German publishing house Manesse VerlagParent companyPenguin Random HouseFounded1944Country of originGermanyHeadquarters locationMunichKey peopleHorst LauingerFiction genresClassic LiteratureOfficial websitewww.manesse.ch The Manesse Verlag is a German publishing house for classical literature, founded in 1944 in Zürich in Switzerland. It belongs today to Random House publishing group based in Munich. The publishing house is mainly known for its library of world literature.[1] It also...

この項目には、一部のコンピュータや閲覧ソフトで表示できない文字が含まれています(詳細)。 数字の大字(だいじ)は、漢数字の一種。通常用いる単純な字形の漢数字(小字)の代わりに同じ音の別の漢字を用いるものである。 概要 壱万円日本銀行券(「壱」が大字) 弐千円日本銀行券(「弐」が大字) 漢数字には「一」「二」「三」と続く小字と、「壱」「�...

2016年美國總統選舉 ← 2012 2016年11月8日 2020 → 538個選舉人團席位獲勝需270票民意調查投票率55.7%[1][2] ▲ 0.8 % 获提名人 唐納·川普 希拉莉·克林頓 政党 共和黨 民主党 家鄉州 紐約州 紐約州 竞选搭档 迈克·彭斯 蒂姆·凱恩 选举人票 304[3][4][註 1] 227[5] 胜出州/省 30 + 緬-2 20 + DC 民選得票 62,984,828[6] 65,853,514[6]...

Japanese manga series Alien NineNorth American cover of Alien Nine volume 1エイリアン9(Eirian Nain)GenreScience fiction[1] MangaWritten byHitoshi TomizawaPublished byAkita ShotenEnglish publisherUS: CPM PressMagazineYoung ChampionDemographicSeinenOriginal run9 June 1998 – 24 August 1999Volumes3 (List of volumes) Original video animationDirected byJiro Fujimoto (epi. 1)Yasuhiro Irie (epi. 2–4)Written bySadayuki MuraiMusic byKuniaki HaishimaStudioJ.C.St...

Частина серії проФілософіяLeft to right: Plato, Kant, Nietzsche, Buddha, Confucius, AverroesПлатонКантНіцшеБуддаКонфуційАверроес Філософи Епістемологи Естетики Етики Логіки Метафізики Соціально-політичні філософи Традиції Аналітична Арістотелівська Африканська Близькосхідна іранська Буддій�...

For other uses, see History of England (disambiguation). English history redirects here. For the Jon English album, see English History (album). Part of a series on the History of England Timeline Prehistoric Britain Roman Britain Medieval period Economy in the Middle Ages Sub-Roman Britain Anglo-Saxon period English unification High Middle Ages Norman Conquest Norman period Late Middle Ages Black Death in England Tudor period Elizabethan era English Renaissance Stuart period English Civil W...

2010 studio album by Colour RevoltThe CradleStudio album by Colour RevoltReleased2010GenreIndie rockLength43:41LabelDualtoneProducerHank SullivantColour Revolt chronology Plunder, Beg and Curse(2008) The Cradle(2010) Professional ratingsReview scoresSourceRatingAbsolutePunk.net(87%)[1]AllMusic[2] The Cradle is the second full-length album from Oxford, Mississippi, indie-rock band, Colour Revolt. It is the band's first since drummer Len Clark, bassist Patrick Addison, a...

Germanic people in Northern Europe mentioned by Tacitus Map showing the Roman empire in AD 125 and contemporary barbarian Europe, showing two possible locations of the Sitones. One, based on Tacitus, places them in central Sweden. Another view places them roughly in modern Estonia and/or Finland. The Sitones were a Germanic people living somewhere in Northern Europe in the first century CE. They are mentioned only by Cornelius Tacitus in 97 CE in Germania.[1] Tacitus considered them s...

Invasion of southern Lebanon by Israel as part of the Lebanese Civil War Not to be confused with the South Lebanon conflict (1985–2000). 1978 South Lebanon conflictPart of the Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon and the Israeli–Lebanese conflictIsraeli soldiers meeting with Lebanese ex-military officer Saad Haddad during the invasionDate14–21 March 1978LocationSouth Governorate and Nabatieh GovernorateResult Israeli victoryTerritorialchanges Palestinian withdrawal from South Lebanon...

Archaeological site in Indonesia This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (June 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Ratu BokoThe gate of Ratu Boko compoundGeneral informationArchitectural stylecandi, fortified settlement complexTown or citynear Yogyakarta (city), YogyakartaCountryIndonesiaCoordinates7°46′12″S 110°29′20″E ...