Dictionary of Old Tupi

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Rute perjalanan Willem van Ruysbroeck, 1253-1255. Willem van Ruysbroeck (1210 - 1270) adalah seorang rohaniawan Kristen dari ordo Fransiskan dan penjelajah. Ia berasal dari kota Rubrouck, Flandria, yang sekarang termasuk région Nord-Pas-de-Calais di Prancis utara yang berbatasan dengan Belgia. Namanya dieja secara bermacam-macam, antara lain Ruysbroeck, Rubroek, Ruysbroek, Roebroeck, Rubroeck, Roebroek, Rubruck, Ruysbrock, Ruysbrok, dan Rubruquius. Ia termasyhur terutama sebagai salah seoran...

Mohammed Al-Owais oleh Kirill Venediktov, 2018Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Mohammed Al-OwaisTanggal lahir 10 Oktober 1991 (umur 32)Tempat lahir Al-Hasa, Arab SaudiTinggi 187 cm (6 ft 2 in)Posisi bermain Penjaga gawangInformasi klubKlub saat ini Al-Ahli SCNomor 33Karier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2017 – Al-Ahli SC 23 (0)Tim nasional2015 – Arab Saudi 7 (0) * Penampilan dan gol di klub senior hanya dihitung dari liga domestik Mohammed Al-Owais (lahir 10 Oktober 1991) ...

Vejrø Vejrø north of Lolland. Vejrø is a Danish island north of Lolland. It covers an area of 1.57 square kilometres (0.61 square miles) and has two inhabitants (as of 2005[update]). The island is private property; for tourists, it offers a marina, an airfield, and some cottages for rent. External links Vejrø 55°02′N 11°22′E / 55.033°N 11.367°E / 55.033; 11.367 vteIslands of Denmark Baltic Sea Zealand Funen Bornholm Christiansø (Ertholmene) Islands...

Yassine Beno Beno pada 2023Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Yassine Beno[1]Tanggal lahir 4 April 1991 (umur 33)[1]Tempat lahir Montreal, Quebec, KanadaTinggi 195 cm (6 ft 5 in)[2][3]Posisi bermain Penjaga gawangInformasi klubKlub saat ini Al-HilalNomor 37Karier junior1999–2010 Wydad CasablancaKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2010–2012 Wydad Casablanca 10 (0)2012–2014 Atlético Madrid B 47 (0)2012–2016 Atlético Madrid 0 (0)2014–20...

Casino resort in Las Vegas, Nevada Red Rock ResortRed Rock Resort in 2010 Location Summerlin South, Nevada, U.S. Address 11011 West Charleston Boulevard[1]Opening dateApril 18, 2006; 17 years ago (2006-04-18)ThemeModern/desertNo. of rooms796Total gaming space118,309 sq ft (10,991.3 m2)Notable restaurantsT-Bones ChophouseYard HouseLucille's SmokehouseCasino typeLand-basedOwnerStation CasinosRenovated in2006–07, 2014, 2019–20Coordinates36°9′1...

Questa voce sull'argomento stagioni delle società calcistiche italiane è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Voce principale: Associazione Calcio Giacomense. Associazione Calcio GiacomenseStagione 2012-2013Sport calcio Squadra Giacomense Allenatore Fabio Gallo poi Leonardo Rossi Presidente Walter Mattioli Lega Pro Seconda Divisione11º posto nel girone A. Maggiori presenzeCampionato: No...

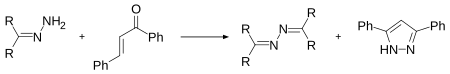

Organic compounds - Hydrazones Structure of the hydrazone functional group Hydrazones are a class of organic compounds with the structure R1R2C=N−NH2.[1] They are related to ketones and aldehydes by the replacement of the oxygen =O with the =N−NH2 functional group. They are formed usually by the action of hydrazine on ketones or aldehydes.[2][3] Synthesis Hydrazine, organohydrazines, and 1,1-diorganohydrazines react with aldehydes and ketones to give hydrazones. Ph...

2023 smartwatch developed by Google Pixel Watch 2A Pixel Watch 2 on display at a store inShibuya Stream in Tokyo, JapanCodenameEosAuroraBrandGoogleSeriesPixelCompatible networks LTE UMTS First releasedOctober 12, 2023; 6 months ago (2023-10-12)Availability by region30 countriesPredecessorPixel WatchTypeSmartwatchDimensionsD: 41 mm (1.6 in)H: 12.3 mm (0.48 in)Mass31 g (1.1 oz)Operating systemWear OS 4.0System-on-chipQualcomm Snapdragon ...

Variants of the human immunodeficiency virus Human immunodeficiency viruses Phylogenetic tree of the SIV and HIV viruses Scientific classification (unranked): Virus Realm: Riboviria Kingdom: Pararnavirae Phylum: Artverviricota Class: Revtraviricetes Order: Ortervirales Family: Retroviridae Subfamily: Orthoretrovirinae Genus: Lentivirus Groups included Human immunodeficiency virus 1 Human immunodeficiency virus 2 Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa Simian immunodeficiency vi...

Former U.S. publishing house This article is about the former publishing house. For the current imprint, see Perseus Book Group. Vanguard PressFoundedMarch 1926; 98 years ago (March 1926)FounderRoger BaldwinScott NearingTrustees of the Garland FundDefunct1988; 36 years ago (1988)SuccessorRandom HouseCountry of originUnited StatesHeadquarters locationNew York CityKey peopleRex Stout (1926–1928)James Henle (1928–1952)Evelyn Shrifte (1952–1988)Publication typ...

JorimGodeungeo-jorimTempat asalKoreaMasakan nasional terkaitHidangan KoreaHidangan serupaNimonoSunting kotak info • L • BBantuan penggunaan templat ini Media: Jorim Nama KoreaHangul조림 Alih AksarajorimMcCune–ReischauerchorimIPA[tɕo.ɾim] Jorim (조림) adalah sebuah hidangan Korea yang terbuat dari sayur, daging, ikan, makanan laut atau tahu yang direbus dan dibumbui dengan kaldu. Hidangan Jorim biasanya berbahan dasar kecap, selain gochujang (고추장, sau...

Gymnastics at the Olympics Gymnasticsat the Games of the II OlympiadGymnastics pictogramVenueVélodrome de VincennesDates29–30 JulyNo. of events1 (1 men, 0 women)Competitors135 from 8 nations← 18961904 → Men's artistic individual all-aroundat the Games of the II OlympiadGymnastics competitions at the 1900 Summer Olympics. Gold medalist Gustave Sandras is depicted at top center.VenueVélodrome de VincennesDates29–30 JulyCompetitors135 from 8 natio...

Roman lawyer, author and magistrate (61 – c.113) For the beer, see Pliny the Younger (beer). Pliny the YoungerGaius Plinius Caecilius SecundusEngraving of Pliny the YoungerBornGaius Caecilius CiloAD 61Como, Roman Italy, Roman EmpireDiedc. AD 113 (aged c. 52)Bithynia, Roman EmpireOccupation(s)Politician, judge, authorNotable workEpistulaeParentsLucius Caecilius Cilo (father)Plinia Marcella (mother) Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, born Gaius Caecilius or Gaius Caecilius Cilo (61 – c...

American baseball player (1898-1969) Baseball player Frank ShellenbackPitcherBorn: (1898-12-16)December 16, 1898Joplin, Missouri, U.S.Died: August 17, 1969(1969-08-17) (aged 70)Newton, Massachusetts, U.S.Batted: RightThrew: RightMLB debutMay 8, 1918, for the Chicago White SoxLast MLB appearanceJuly 5, 1919, for the Chicago White SoxMLB statisticsWin–loss record10–15Earned run average3.06Strikeouts57 Teams Chicago White Sox (1918–1919) Frank Victor Shel...

Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of DumbledoreSutradaraDavid YatesProduser David Heyman J. K. Rowling Steve Kloves Lionel Wigram Tim Lewis Skenario J. K. Rowling Steve Kloves CeritaJ. K. RowlingBerdasarkanCharactersoleh J. K. RowlingPemeran Eddie Redmayne Katherine Waterston Dan Fogler Alison Sudol Ezra Miller Callum Turner William Nadylam Poppy Corby-Tuech Jessica Williams Jude Law Mads Mikkelsen Penata musikJames Newton HowardSinematograferGeorge RichmondPenyuntingMark DayPerusahaanprodu...

هذه المقالة بحاجة لصندوق معلومات. فضلًا ساعد في تحسين هذه المقالة بإضافة صندوق معلومات مخصص إليها. يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (ديسمبر 2018) رتبة م...

This is an archive of past discussions. Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. Archive 1 ← Archive 4 Archive 5 Archive 6 Requested move 13 January 2023 The following is a closed discussion of a requested move. Please do not modify it. Subsequent comments should be made in a new section on the talk page. Editors desiring to contest the closing decision should consider a move review after di...

此條目可参照英語維基百科相應條目来扩充。若您熟悉来源语言和主题,请协助参考外语维基百科扩充条目。请勿直接提交机械翻译,也不要翻译不可靠、低品质内容。依版权协议,译文需在编辑摘要注明来源,或于讨论页顶部标记{{Translated page}}标签。 “埃贝尔”号的姊妹舰“美洲虎”号(英语:SMS Jaguar) 历史 德意志帝国 艦名 “埃贝尔”号炮舰艦名出處 “埃贝尔”号�...

Rithvik DhanjaniLahir5 November 1988 (umur 35)[1]Madhya Pradesh, IndiaKebangsaanIndianPekerjaanaktor, penariTahun aktif2009 - sekarangSuami/istriAsha Negi (2011-sekarang)[2] Rithvik Dhanjani (lahir 5 November 1988) adalah aktor televisi India. Dia memainkan Arjun Digvijay Kirloskar di Pavitra Rishta.[3] Dhanjani telah menjadi tuan rumah dan berpartisipasi dalam banyak reality show seperti Nach Baliye, Dare 2 Dance, India's Best Dramebaaz dan V Distraction. I...

William (Willy) Alfred Higinbotham (* 25. Oktober 1910 in Bridgeport, Connecticut; † 10. November 1994 in Gainesville, Georgia) war ein US-amerikanischer Physiker und der erste Generalsekretär der Federation of American Scientists. Er gilt als Erfinder des ersten Videospiels, Tennis for Two (1958). Laufbahn Higinbotham begann sein Physikstudium am Williams College und beendete es bis zum Ausbruch des Zweiten Weltkrieges an der Cornell University im US-Bundesstaat New York. Es folgten eine ...