Climate of Asia

The climate of Asia is dry across its southwestern region. Some of the largest daily temperature ranges on Earth occur in the western part of Asia. The monsoon circulation dominates across the southern and eastern regions, due to the Himalayas forcing the formation of a thermal low which draws in moisture during the summer. The southwestern region of the continent experiences low relief as a result of the subtropical high pressure belt; they are hot in summer, warm to cool in winter, and may snow at higher altitudes. Siberia is one of the coldest places in the Northern Hemisphere, and can act as a source of arctic air mass for North America. The most active place on Earth for tropical cyclone activity lies northeast of the Philippines and south of Japan, and the phase of the El Nino-Southern Oscillation modulates where in Asia landfall is more likely to occur. Many parts of Asia are being impacted by climate change. TemperatureThe Southern sections of Asia are mild to hot, while far northeastern areas such as Siberia are very cold, and East Asia has a temperate climate. The highest temperature recorded in Asia was 54 °C (at Ahvaz Airport, Iran on June 29, 2017, and at Tirat Zvi, Israel on June 21, 1942). West-central Asia experiences some of the largest diurnal temperature ranges on Earth. The lowest temperature measured was −67.8 °C (−90.0 °F) at Verkhoyansk and Oymyakon, both in Sakha Republic of Russia on February 7, 1892, and February 6, 1933, respectively.[2] PrecipitationA large annual rainfall minimum, composed primarily of deserts, stretches from the Gobi Desert in Mongolia west-southwest through the Taklamakan Desert in Western China, the Thar Desert in Western India and Iranian Plateau into the Arabian Desert in the Arabian Peninsula. Rainfall around the continent is across its southern portion from Eastern India and Northeast India across the Philippines, Indochina, Malay Peninsula, Malay Archipelago and Southern China into Korean Peninsula Taiwan and Japan due to the Monsoon advecting moisture primarily from the Indian Ocean into the region.[3] The monsoon trough can reach as far north as the 40th parallel in East Asia during August before moving southward thereafter. Its poleward progression is accelerated by the onset of the summer monsoon which is characterized by the development of lower air pressure (a thermal low) over the warmest part of Asia.Mawsynram in Meghalaya received annually 11872 cm of rainfall[4][5][6] Cherrapunji. The highest recorded rainfall in a single year was 22,987 mm (904.9 in) in 1861. The 38-year average at Mawsynram, Meghalaya, India is 11,872 mm (467.4 in).[7] Lower rainfall maxima are found around Turkey and central Russia. In March 2008, La Niña caused a drop in sea surface temperatures around Southeast Asia by an amount of 2 °C. It also caused heavy rains over Malaysia, Philippines and Indonesia.[8] Monsoon The Asian monsoons may be classified into a few sub-systems, such as the South Asian Monsoon which affects the Indian subcontinent and surrounding regions, and the East Asian Monsoon which affects southern China, Korea and parts of Japan. The southwestern summer monsoons occur from June through September. The Thar Desert and adjoining areas of the northern and central Indian subcontinent heats up considerably during the hot summers, which causes a low pressure area over the northern and central Indian subcontinent. To fill this void, the moisture-laden winds from the Indian Ocean rush into the subcontinent. These winds, rich in moisture, are drawn towards the Himalayas, creating winds blowing storm clouds towards the subcontinent. The Himalayas act like a high wall, blocking the winds from passing into Central Asia, thus forcing them to rise. With the gain in altitude of the clouds, the temperature drops and precipitation occurs. Some areas of the subcontinent receive up to 10,000 mm (390 in) of rain. The moisture-laden winds on reaching the southernmost point of the Indian subcontinent, due to its topography, become divided into two parts: the Arabian Sea Branch and the Bay of Bengal Branch. The Arabian Sea Branch of the Southwest Monsoon first hits the Western Ghats of the coastal state of Kerala, India, thus making it the first state in India to receive rain from the Southwest Monsoon. This branch of the monsoon moves northwards along the Western Ghats with precipitation on coastal areas, west of the Western Ghats. The eastern areas of the Western Ghats do not receive much rain from this monsoon as the wind does not cross the Western Ghats. The Bay of Bengal Branch of Southwest Monsoon flows over the Bay of Bengal heading towards northeast India and Bengal, picking up more moisture from the Bay of Bengal. The winds arrive at the Eastern Himalayas with large amounts of rain. Mawsynram, situated on the southern slopes of the Eastern Himalayas in Shillong, India, is one of the wettest places on Earth. After the arrival at the Eastern Himalayas, the winds turns towards the west, travelling over the Indo-Gangetic Plain at a rate of roughly 1–2 weeks per state[citation needed], pouring rain all along its way. June 1 is regarded as the date of onset of the monsoon in India, as indicated by the arrival of the monsoon in the southernmost state of Kerala. The monsoon accounts for 95% of the rainfall in India[citation needed]. Indian agriculture (which accounts for 25% of the GDP and employs 70% of the population) is heavily dependent on the rains, for growing crops especially like cotton, rice, oilseeds and coarse grains. A delay of a few days in the arrival of the monsoon can badly affect the economy, as evidenced in the numerous droughts in India in the 1990s. The monsoon is widely welcomed and appreciated by city-dwellers as well, for it provides relief from the climax of summer heat in June.[9] However, the condition of the roads take a battering each year. Often houses and streets are waterlogged and the slums are flooded in spite of having a drainage system. This lack of city infrastructure coupled with changing climate patterns causes severe economical loss including damage to property and loss of lives, as evidenced in the 2005 Maharashtra floods. Bangladesh and certain regions of India like Assam and West Bengal, also frequently experience heavy floods during this season. And in the recent past, areas in India that used to receive scanty rainfall throughout the year, like the Thar Desert, have surprisingly ended up receiving floods due to the prolonged monsoon season. The influence of the Southwest Monsoon is felt as far north as in China's Xinjiang. It is estimated that about 70% of all precipitation in the central part of the Tian Shan Mountains falls during the three summer months, when the region is under the monsoon influence; about 70% of that is directly of "cyclonic" (i.e., monsoon-driven) origin (as opposed to "local convection").[10]  Around September, with the sun fast retreating south, the northern land mass of the Indian subcontinent begins to cool off rapidly. With this air pressure begins to build over northern India, the Indian Ocean and its surrounding atmosphere still holds its heat. This causes the cold wind to sweep down from the Himalayas and Indo-Gangetic Plain towards the vast spans of the Indian Ocean south of the Deccan peninsula. This is known as the Northeast Monsoon or Retreating Monsoon. While traveling towards the Indian Ocean, the dry cold wind picks up some moisture from the Bay of Bengal and pours it over peninsular India and parts of Sri Lanka. Cities like Madras, which get less rain from the Southwest Monsoon, receives rain from this Monsoon. About 50% to 60% of the rain received by the state of Tamil Nadu is from the Northeast Monsoon.[11] In Southern Asia, the northeastern monsoons take place from December to early March when the surface high-pressure system is strongest.[12] The jet stream in this region splits into the southern subtropical jet and the polar jet. The subtropical flow directs northeasterly winds to blow across southern Asia, creating dry air streams which produce clear skies over India. Meanwhile, a low pressure system develops over South-East Asia and Australasia and winds are directed toward Australia known as a monsoon trough. The East Asian monsoon affects large parts of Indochina, Philippines, China, Korea and Japan. It is characterised by a warm, rainy summer monsoon and a cold, dry winter monsoon. The rain occurs in a concentrated belt that stretches east–west except in East China where it is tilted east-northeast over Korea and Japan. The seasonal rain is known as Meiyu in China, Changma in Korea, and Bai-u in Japan, with the latter two resembling frontal rain. The onset of the summer monsoon is marked by a period of premonsoon rain over South China and Taiwan in early May. From May through August, the summer monsoon shifts through a series of dry and rainy phases as the rain belt moves northward, beginning over Indochina and the South China Sea (May), to the Yangtze River Basin and Japan (June) and finally to North China and Korea (July). When the monsoon ends in August, the rain belt moves back to South China. Severe weatherTornadoesBangladesh and the eastern parts of India are very exposed to destructive tornadoes. Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Japan have the highest number of reported tornadoes in Asia. The single deadliest tornado ever recorded struck the Manikganj District of Bangladesh on 26 April 1989, killing an estimated 1,300 people, injuring 12,000, and leaving approximately 80,000 people homeless.[13] Throughout China, an estimated 100 tornadoes may occur per year with a few exceeding F4 in intensity, with activity most prevalent in eastern regions.[14] During the period of 1948 until 2013, 4763 tornadoes were confirmed in China.[15] Tropical cyclones Many portions of Asia bordering the Indian and Pacific oceans are regularly affected by tropical cyclones. In southern Asia, Bangladesh is vulnerable to storm surge flooding from landfalling tropical cyclones. The low-lying and populated country has a history of the deadliest tropical cyclones. On November 12, 1970, a cyclone struck Bangladesh, then known as East Pakistan, producing a 6.1 m (20 ft) storm surge that killed at least 300,000 people. This made it the deadliest tropical cyclone on record.[16] The cyclone wrecked about 400,000 houses, 99,000 boats, and 3,500 schools. The local government's lack of response to the storm was a partial factor in the Bangladesh Liberation War, one of the first instances in which a natural disaster led to a civil war.[17] In neighboring Myanmar, Cyclone Nargis struck the low-lying Irrawaddy Delta in May 2008 with strong winds and a 3.7 m (12 ft) storm surge. Nargis killed an estimated 140,000 people, becoming the country's worst natural disaster on record, and left more than US$10 billion in damage, with more than 700,000 homes damaged or destroyed, leaving more than 1 million people homeless.[18][19][20] Cyclones in the Indian Ocean have hit Asia as far west as Yemen, as demonstrated by Cyclone Chapala striking the country in October 2015.[21][22] The strongest cyclone on record in the Bay of Bengal was a super cyclonic storm in 1999, which made landfall in the eastern Indian province of Odisha in October 1999 with winds of 260 km/h (160 mph). The cyclone killed 9,887 people across Odisha, with 1.6 million houses damaged or destroyed, causing US$1.5 billion in damage.[23][24][25] The Pacific Ocean north of the equator is the most active tropical cyclone basin on Earth, accounting for roughly one-third of all storms annually.[26] Most tropical cyclones form on the side of the subtropical ridge closer to the equator, then move poleward past the ridge axis before recurving into the main belt of the Westerlies.[27] Each year, an average of nine tropical cyclones strike the Philippines, mostly along Luzon and the eastern Visayas. Tropical cyclones contributed to more than half of the annual rainfall in western Luzon.[28][29][30] Typhoons – the regional name for an intense tropical cyclone – affect southeastern Asia more often during La Niña years, due to the westward position of the subtropical ridge. During El Niño years, the position of the subtropical ridge increases the threat to Japan.[26] Climate change Climate change is particularly important in Asia, as the continent accounts for the majority of the human population. Warming since the 20th century is increasing the threat of heatwaves across the entire continent.[33]: 1459 Heatwaves lead to increased mortality, and the demand for air conditioning is rapidly accelerating as the result. By 2080, around 1 billion people in the cities of South and Southeast Asia are expected to experience around a month of extreme heat every year.[33]: 1460 The impacts on water cycle are more complicated: already arid regions, primarily located in West Asia and Central Asia, will see more droughts, while areas of East, Southeast and South Asia which are already wet due to the monsoons will experience more flooding.[33]: 1459 The waters around Asia are subjected to the same impacts as elsewhere, such as the increased warming and ocean acidification.[33]: 1465 There are many coral reefs in the region, and they are highly vulnerable to climate change,[33]: 1459 to the point practically all of them will be lost if the warming exceeds 1.5 °C (2.7 °F).[34][35] Asia's distinctive mangrove ecosystems are also highly vulnerable to sea level rise.[33]: 1459 Asia also has more countries with large coastal populations than any other continent, which would cause large economic impacts from sea level rise.[33]: 1459 Water supplies in the Hindu Kush region will become more unstable as its enormous glaciers, known as the "Asian water towers", gradually melt.[33]: 1459 These changes to water cycle also affect vector-borne disease distribution, with malaria and dengue fever expected to become more prominent in the tropical and subtropical regions.[33]: 1459 Food security will become more uneven, and South Asian countries could experience significant impacts from global food price volatility.[33]: 1494  Historical emissions from Asia are lower than those from Europe and North America. However, China has been the single largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the 21st century, while India is the third-largest. As a whole, Asia currently accounts for 36% of world's primary energy consumption, which is expected to increase to 48% by 2050. By 2040, it is also expected to account for 80% of the world's coal and 26% of the world's natural gas consumption.[33]: 1468 While the United States remains the world's largest oil consumer, by 2050 it is projected to move to third place, behind China and India.[33]: 1470 While nearly half of the world's new renewable energy capacity is built in Asia,[33]: 1470 this is not yet sufficient in order to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. They imply that the renewables would account for 35% of total energy consumption in Asia by 2030.[33]: 1471 Climate change adaptation is already a reality for many Asian countries, with a wide range of strategies attempted across the continent.[33]: 1534 Important examples include the growing implementation of climate-smart agriculture in certain countries or the "sponge city" planning principles in China.[33]: 1534 While some countries have drawn up extensive frameworks such as the Bangladesh Delta Plan or Japan's Climate Adaptation Act,[33]: 1508 others still rely on localized actions that are not effectively scaled up.[33]: 1534References

External links

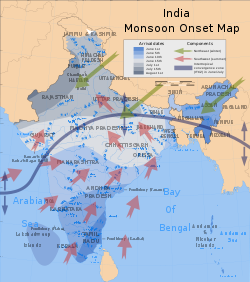

|