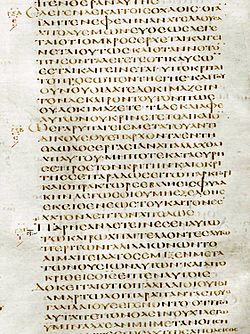

Byzantine text-type In the textual criticism of the New Testament, the Byzantine text-type (also called Traditional Text, Ecclesiastical Text, Constantinopolitan Text, Antiocheian Text, or Syrian Text) is one of the main text types. The New Testament text of the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the Patriarchal Text, are based on this text-type. Similarly, the Aramaic Peshitta which often conforms to the Byzantine text is used as the standard version in the Syriac tradition, including the Syriac Orthodox Church and the Chaldean Church.[1][2][3] It is the form found in the largest number of surviving manuscripts of the Greek New Testament. Consequently, the Majority Text methodology, which prefers the readings that are most common or which are found in the great preponderance of manuscripts, generates a text that is Byzantine text (in turn leading to the Byzantine priority rule-of-thumb.) Whilst varying in around 1,800 places from printed editions,[4] the Byzantine text-type also underlies the Textus Receptus Greek text used for most Reformation-era (Protestant) translations of the New Testament into vernacular languages.[5] The Byzantine text is also found in a few modern Eastern Orthodox editions, as the Byzantine textual tradition has continued in the Eastern Orthodox Church into the present time. The text used by the Orthodox Church is supported by late minuscule manuscripts. It is commonly accepted as the standard Byzantine text.[6] There are also some textual critics such as Robinson and Hodges who still favor the Byzantine Text, and have produced Byzantine-majority critical editions of the Greek New Testament.[7] This view was famously defended by John Burgon.[8] Modern translations (since 1900) mainly use eclectic editions that conform more often to the Alexandrian text-type, which has been viewed as the most accurate text-type by most scholars,[9] although some modern translations that use the Byzantine text-type have been created.[10] Manuscripts The earliest clear notable patristic witnesses to the Byzantine text come from early eastern church fathers such as Gregory of Nyssa (335 – c. 395), John Chrysostom (347 – 407), Basil the Great (330 – 379) and Cyril of Jerusalem (313 – 386). [11][12][13]: 130 The fragmentary surviving works of Asterius the Sophist († 341) have also been considered to conform to the Byzantine text.[12]: 358 Although somewhat closer to the Alexandrian text, the quotations of Clement of Alexandria (150 – 215) sometimes contain readings which agree with the later Byzantine text-type. [14]: 229 The incomplete surviving translation of Wulfila (d. 383) into Gothic is often thought to derive from the Byzantine text type or an intermediary between the Byzantine and Western text types.[15] The second or third earliest translation to witness to a Greek base conforming generally to the Byzantine text in the Gospels is the Syriac Peshitta (though it has many Alexandrian and Western readings);[2][3] usually dated to the beginning of the 5th century;[13]: 98 although in respect of several much contested readings, such as Mark 1:2 and John 1:18, the Peshitta rather supports the Alexandrian witnesses. Despite being characterized by mixed readings, significant Byzantine components also exist in the Syro-Palestinian manuscripts, which likely originated from the 5th century.[16]: 155  Dating from the fourth century, and hence possibly earlier than the Peshitta, is the Ethiopic version of the Gospels; best represented by the surviving fifth and sixth century manuscripts of the Garima Gospels and classified by Rochus Zuurmond as "early Byzantine". Zuurmond notes that, especially in the Gospel of John, the form of the early Byzantine text found in the Ethiopic Gospels is quite different from the later Greek Majority Text, and agrees in a number of places with Papyrus 66.[16]: 231–252 In the very early 7th century, Thomas Herakel worked on a revision of the Philoxenian version, thus producing the Harklean version in Syriac. This text very closely resembles the Byzantine text-type and due to its wide distribution, it is preserved in over 120 manuscripts. Many of the extant Georgian and Armenian manuscripts also conform to the Byzantine text-type, although this is due to the manuscripts having gone through revisions to bring them closer to the Byzantine text.[16][2] Additionally, the Byzantine text is the textual basis of the Old Church Slavonic manuscripts of the Bible, although they sometimes contain readings from other textual traditions.[2] Some debate exists on the manuscript basis of Jerome's Latin Vulgate and if this text was influenced by the Byzantine text. Wordsworth concluded that Jerome mainly used a text-type similar to Codex Siniaticus and Vaticanus, however his conclusions were rejected by H. J. Vogels who instead argued that the Greek manuscripts used by Jerome mostly agreed with the Byzantine text. Vogel's analysis of the Vulgate was criticized by both F. C. Burkitt and Lagrange, Burkitt instead argued that Jerome's Vulgate was influenced by multiple Greek manuscripts from different text-types, some of which were similar to Codex Alexandrinus while others similar to Codex Vaticanus.[2]: 355–356 Individual readings in agreement with the later Byzantine text have been found in the very early papyri, such as 𝔓46. Some such as Harry Sturz have concluded from this that the Byzantine text-type must have had an early existence, however others have been cautious in making this conclusion. According to Zuntz, although some Byzantine readings may be ancient, the Byzantine tradition as a whole originates from a later period, not as a creation but as a process of choosing between early variants.[12]: 231-232 It has also been questioned if some of the readings found in the early papyri which agree with later Byzantine readings are genetically significant or accidental.[16] Notable manuscripts

Other manuscripts

Codex Mutinensis (H), Codex Cyprius (K), Codex Mosquensis I (Kap), Campianus (M), Petropolitanus Purp. (N), Sinopensis (O), Guelferbytanus A (P), Guelferbytanus B (Q), Nitriensis (R), Nanianus (U), Monacensis (X), Tischendorfianus IV (Γ), Sangallensis (Δ) (except Mark), Tischendorfianus III (Λ), Petropolitanus (Π), Rossanensis (Σ), Beratinus (Φ), Dionysiou (Ω), Vaticanus 2066 (Uncial 046), Uncial 047, 049, 052, 053, 054, 056, 061, 063, 064, 065, 069 (?), 093 (Acts), 0103, 0104, 0105, 0116, 0120, 0133, 0134, 0135, 0136, 0142, 0151, 0197, 0211, 0246, 0248, 0253, 0255, 0257, 0265, 0269 (mixed), 0272, 0273 (?).

More than 80% of minuscules represent the Byzantine text.[17]: 128 2, 3, 6 (Gospels and Acts), 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15, 18, 21, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28 (except Mark), 29, 30, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 50, 52, 53, 54, 55, 57, 58, 60, 61 (Gospels and Acts), 63, 65, 66, 68, 69 (except Paul), 70, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 80, 82, 83, 84, 89, 90, 92, 93, 95, 97, 98, 99, 100, 103, 104 (except Paul), 105, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 116, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 155, 156, 159, 162, 167, 169, 170, 171, 177, 180 (except Acts), 181 (only Rev.), 182, 183, 185, 186, 187, 189, 190, 192, 193, 194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205 (Epistles), 206 (except Cath.), 207, 208, 209 (except Gospels and Rev.), 210, 212, 214, 215, 217, 218 (except Cath. and Paul), 219, 220, 221, 223, 224, 226, 227, 231, 232, 235, 236, 237, 240, 243, 244, 245, 246, 247, 248, 250, 254 (except Cath.), 256 (except Paul), 259, 260, 261, 262, 263 (except Paul), 264, 266, 267, 268, 269, 270, 272, 275, 276, 277, 278a, 278b, 280, 281, 282, 283, 284, 285, 286, 287, 288, 289, 290, 291, 292, 293, 297, 300, 301, 302, 303, 304, 305, 306, 308, 309, 313, 314, 316, 319, 320, 324, 325, 327, 328, 329, 330 (except Paul), 331, 334, 335, 337, 342, 343, 344, 347, 350, 351, 352, 353, 354, 355, 356, 357, 358, 359, 360, 361, 362, 364, 365 (except Paul), 366, 367, 368, 369, 371, 373, 374, 375, 376, 378 (except Cath.), 379, 380, 381, 384, 385, 386, 387, 388, 390, 392, 393, 394, 395, 396, 398 (except Cath.), 399, 401, 402, 404, 405, 407, 408, 409, 410, 411, 412, 413, 414, 415, 417, 418, 419, 422, 425, 426, 429 (Paul and Rev.), 431 (except Acts and Cath.), 432, 438, 439, 443, 445, 446, 448, 449, 450, 451 (except Paul), 452, 454, 457, 458, 459 (except Paul), 461, 465, 466, 469, 470, 471, 473, 474, 475, 476, 477, 478, 479, 480, 481, 482, 483, 484, 485, 490, 491, 492, 493, 494, 496, 497, 498, 499, 500, 501, 502, 504, 505, 506, 507, 509, 510, 511, 512, 514, 516, 518, 519, 520, 521, 522 (except Acts and Cath.), 523, 524, 525, 526, 527, 528, 529, 530, 531, 532, 533, 534, 535, 538, 540, 541, 546, 547, 548, 549, 550, 551, 553, 554, 556, 558, 559, 560, 564, 568, 570, 571, 573, 574, 575, 577, 578, 580, 583, 584, 585, 586, 587, 588, 592, 593, 594, 596, 597, 600, 601, 602, 603, 604, 605, 607, 610 (in Cath.), 614 (in Cath.), 616, 618, 620, 622, 624, 625, 626, 627, 628, 632, 633, 634, 637, 638, 639, 640, 642 (except Cath.), 644, 645, 648, 649, 650, 651, 655, 656, 657, 660, 662, 663, 664, 666, 668, 669, 672, 673, 674, 677, 680, 684, 685, 686, 688, 689, 690, 691, 692, 694, 696, 698, 699, 705, 707, 708, 711, 714, 715, 717, 718, 721, 724, 725, 727, 729, 730, 731, 734, 736, 737, 739, 741, 745, 746, 748, 750, 754, 755, 756, 757, 758, 759, 760, 761, 762, 763, 764, 765, 768, 769, 770, 773, 774, 775, 777, 778, 779, 781, 782, 783, 784, 785, 786, 787, 789, 790, 793, 794, 797, 798, 799, 801, 802, 806, 808, 809, 811, 818, 819, 820, 824, 825, 830, 831, 833, 834, 835, 836, 839, 840, 841, 843, 844, 845, 846, 848, 852, 853, 857, 858, 860, 861, 862, 864, 866, 867, 868, 870, 877, 880, 884, 886, 887, 889, 890, 893, 894, 896, 897, 898, 900, 901, 902, 904, 905, 906, 910, 911, 912, 914, 916, 917 (Paul), 918 (Paul), 919, 920, 921, 922, 924, 928, 936, 937, 938, 942, 943, 944, 945 (Acts and Cath.), 950, 951, 952, 953, 955, 956, 957, 958, 959, 960, 961, 962, 963, 964, 965, 966, 967, 969, 970, 971, 973, 975, 977, 978, 980, 981, 987, 988, 991, 993, 994, 995, 997, 998, 999, 1000, 1003, 1004, 1006 (Gospels), 1007, 1008, 1010 (?), 1011, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, 1020, 1023, 1024, 1025, 1026, 1028, 1030, 1031, 1032, 1033, 1036, 1044, 1045, 1046, 1050, 1052, 1053, 1054, 1055, 1056, 1057, 1059, 1060, 1061, 1062, 1063, 1065, 1067 (except Cath.), 1068, 1069, 1070, 1072, 1073, 1074, 1075, 1076, 1077, 1078, 1080, 1081, 1083, 1085, 1087, 1088, 1089, 1094, 1099, 1100, 1101, 1103, 1104, 1105, 1107, 1110, 1112, 1119, 1121, 1123, 1129, 1148, 1149, 1150, 1161, 1168, 1169, 1171, 1172, 1173, 1174, 1176, 1177, 1185, 1186, 1187, 1188, 1189, 1190, 1191, 1193, 1196, 1197, 1198, 1199, 1200, 1201, 1202, 1203, 1205, 1206, 1207, 1208, 1209, 1211, 1212, 1213, 1214, 1215, 1217, 1218, 1220, 1221, 1222, 1223, 1224, 1225, 1226, 1227, 1231, 1241 (only Acts), 1251 (?), 1252, 1254, 1255, 1260, 1264, 1277, 1283, 1285, 1292 (except Cath.), 1296, 1297, 1298, 1299, 1300, 1301, 1303, 1305, 1309, 1310, 1312, 1313, 1314, 1315, 1316, 1317, 1318, 1319 (except Paul), 1320, 1323, 1324, 1328, 1330, 1331, 1334, 1339, 1340, 1341, 1343, 1345, 1347, 1350a, 1350b, 1351, 1352a, 1354, 1355, 1356, 1357, 1358, 1359 (except Cath.), 1360, 1362, 1364, 1367, 1370, 1373, 1374, 1377, 1384, 1385, 1392, 1395, 1398 (except Paul), 1400, 1409 (Gospels and Paul), 1417, 1437, 1438, 1444, 1445, 1447, 1448 (except Cath.), 1449, 1452, 1470, 1476, 1482, 1483, 1492, 1503, 1504, 1506 (Gospels), 1508, 1513, 1514, 1516, 1517, 1520, 1521, 1523 (Paul), 1539, 1540, 1542b (only Luke), 1543, 1545, 1547, 1548, 1556, 1566, 1570, 1572, 1573 (except Paul?), 1577, 1583, 1594, 1597, 1604, 1605, 1607, 1613, 1614, 1617, 1618, 1619, 1622, 1628, 1636, 1637, 1649, 1656, 1662, 1668, 1672, 1673, 1683, 1693, 1701, 1704 (except Acts), 1714, 1717, 1720, 1723, 1725, 1726, 1727, 1728, 1730, 1731, 1732, 1733, 1734, 1736, 1737, 1738, 1740, 1741, 1742, 1743, 1745, 1746, 1747, 1748, 1749, 1750, 1752, 1754, 1755a, 1755b, 1756, 1757, 1759, 1761, 1762, 1763, 1767, 1768, 1770, 1771, 1772, 1800, 1821, 1826, 1828, 1829, 1835, 1841 (except Rev.), 1846 (only Acts), 1847, 1849, 1851, 1852 (only in Rev.), 1854 (except Rev.), 1855, 1856, 1858, 1859, 1860, 1861, 1862, 1869, 1870, 1872, 1874 (except Paul), 1876, 1877 (except Paul), 1878, 1879, 1880, 1882, 1883, 1888, 1889, 1891 (except Acts), 1897, 1899, 1902, 1905, 1906, 1907, 1911, 1914, 1915, 1916, 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1932, 1933, 1934, 1936,1937, 1938, 1941, 1946, 1948, 1951, 1952, 1954, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1958, 1964, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1974, 1975, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1986, 1988, 1992, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2003, 2007, 2009, 2013, 2048, 2096, 2098, 2111, 2119, 2125, 2126, 2127 (except Paul), 2132, 2133, 2135, 2138 (only in Rev.), 2139, 2140, 2141, 2142, 2144, 2160, 2172, 2173, 2175, 2176, 2177, 2178, 2181, 2183, 2187, 2189, 2191, 2199, 2218, 2221, 2236, 2261, 2266, 2267, 2273, 2275, 2277, 2281, 2289, 2295, 2300, 2303, 2306, 2307, 2309, 2310, 2311, 2352, 2355, 2356, 2373, 2376, 2378, 2381, 2382, 2386, 2389, 2390, 2406, 2407, 2409, 2414, 2415, 2418, 2420, 2422, 2423, 2424, 2425, 2426, 2430, 2431, 2437, 2441, 2442, 2445, 2447, 2450, 2451, 2452, 2454, 2455, 2457, 2458, 2459, 2466, 2468, 2475, 2479, 2483, 2484, 2490, 2491, 2496, 2497, 2499, 2500, 2501, 2502, 2503, 2507, 2532, 2534, 2536, 2539, 2540, 2545, 2547, 2549, 2550, 2552, 2554, 2555, 2558, 2559, 2562, 2563, 2567, 2571, 2572, 2573, 2578, 2579, 2581, 2584, 2587, 2593, 2600, 2619, 2624, 2626, 2627, 2629, 2631, 2633, 2634, 2635, 2636, 2637, 2639, 2645, 2646, 2649, 2650, 2651, 2653, 2656, 2657, 2658, 2660, 2661, 2665, 2666, 2671, 2673, 2675, 2679, 2690, 2691, 2696, 2698, 2699, 2700, 2704, 2711, 2712, 2716, 2721, 2722, 2723, 2724, 2725, 2727, 2729, 2746, 2760, 2761, 2765, 2767, 2773, 2774, 2775, 2779, 2780, 2781, 2782, 2783, 2784, 2785, 2787, 2790, 2791, 2794, 2815, 2817, 2829.[18][19][17]: 129-140 Distribution by century

461, 1080, 1862, 2142, 2500

399

14, 27, 29, 34, 36e, 63, 82, 92, 100, 135, 144, 151, 221, 237, 262, 278b, 344, 364, 371, 405, 411, 450, 454, 457, 478, 481, 564, 568, 584, 602, 605, 626, 627, 669, 920, 1055, 1076, 1077, 1078, 1203, 1220, 1223, 1225, 1347, 1351, 1357, 1392, 1417, 1452, 1661, 1720, 1756, 1829, 1851, 1880, 1905, 1920, 1927, 1954, 1997, 1998, 2125, 2373, 2414, 2545, 2722, 2790

994, 1073, 1701

7p, 8, 12, 20, 23, 24, 25, 37, 39, 40, 50, 65, 68, 75, 77, 83, 89, 98, 108, 112, 123, 125, 126, 127, 133, 137, 142, 143, 148, 150, 177, 186, 194, 195, 197, 200, 207, 208, 210, 212, 215, 236, 250, 259, 272, 276, 277, 278a, 300, 301, 302, 314, 325, 331, 343, 350, 352, 354, 357, 360, 375, 376, 422, 458, 465, 466, 470, 474, 475, 476, 490, 491, 497, 504, 506, 507, 516, 526, 527, 528, 530, 532, 547, 548, 549, 560, 583, 585, 596, 607, 624, 625, 638, 639, 640, 651, 672, 699, 707, 708, 711, 717, 746, 754, 756, 773, 785, 809, 831, 870, 884, 887, 894, 901, 910, 919, 937, 942, 943, 944, 964, 965, 991, 1014, 1028, 1045, 1054, 1056, 1074, 1110, 1123, 1168, 1174, 1187, 1207, 1209, 1211, 1212, 1214, 1221, 1222, 1244, 1277, 1300, 1312, 1314, 1317, 1320, 1324, 1340, 1343, 1373, 1384, 1438, 1444, 1449, 1470, 1483, 1513, 1514, 1517, 1520, 1521, 1545, 1556, 1570, 1607, 1668, 1672, 1693, 1730, 1734, 1738, 1770, 1828, 1835, 1847, 1849, 1870, 1878, 1879, 1888, 1906, 1907, 1916, 1919, 1921, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1932, 1933, 1934, 1946, 1955, 1980, 1981, 1982, 2001, 2007, 2098, 2132, 2133, 2144, 2172, 2176, 2181, 2183, 2199, 2275, 2277, 2281, 2386, 2295, 2307, 2381, 2386, 2430, 2442, 2447, 2451, 2458, 2468, 2475, 2539, 2547, 2559, 2563, 2567, 2571, 2587, 2637, 2649, 2661, 2723, 2746, 2760, 2782, 2787

665, 657, 660, 1013, 1188, 1191, 1309, 1358, 1340, 1566, 2389, 2415, 2784

2e, 2ap, 3, 9, 11, 15, 21, 32, 44, 46, 49, 57, 73, 76, 78, 80, 84, 95, 97, 105, 110, 111, 116, 119, 120, 122, 129, 132, 134, 138, 139, 140, 146, 156, 159, 162, 183, 187, 193, 196, 199, 202, 203, 217, 224, 226, 231, 240, 244, 245, 247, 261, 264, 267, 268, 269, 270, 275, 280, 281, 282, 297, 304, 306, 319, 320, 329, 334, 337, 347, 351, 353, 355, 356, 366, 374, 387, 392, 395, 396, 401, 407, 408, 419, 438, 439, 443, 452, 471, 485, 499, 502, 505, 509, 510, 514, 518, 520, 524, 529, 531, 535, 538, 550, 551, 556, 570, 571, 580, 587, 618, 620, 622, 637, 650, 662, 673, 674, 688, 692, 721, 736, 748, 750, 760, 765, 768, 770, 774, 777, 778, 779, 782, 787, 793, 799, 808, 843, 857, 860, 862, 877, 893, 896, 902, 911, 916, 922, 924, 936, 950, 967, 971, 973, 975, 980, 987, 993, 998, 1007, 1046, 1081, 1083, 1085, 1112, 1169, 1176, 1186, 1190, 1193, 1197, 1198, 1199, 1200, 1217, 1218, 1224, 1231, 1240, 1301, 1315, 1316, 1318, 1323, 1350a, 1355, 1360, 1364, 1375, 1385, 1437, 1539, 1583, 1673, 1683, 1714, 1737, 1752, 1754, 1755a, 1755b, 1800, 1821, 1826, 1872, 1889, 1914, 1915, 1917, 1926, 1951, 1970, 1971, 1974, 1986, 1988, 2013, 2096, 2126, 2135, 2139, 2173, 2177, 2189, 2191, 2289, 2282, 2426, 2437, 2445, 2459, 2490, 2491, 2507, 2536, 2549, 2550, 2552, 2562, 2639, 2650, 2657, 2671, 2700, 2712, 2725, 2727, 2781, 2785, 2791, 2794

905, 906, 1310, 1341, 1897, 2311

52, 55, 60, 74, 107, 121, 128, 136, 141, 147, 167, 170, 192, 198, 204, 219, 220, 227, 248, 260, 284, 291, 292, 293, 303, 305, 309, 327, 328, 342, 359, 361, 362, 384, 388, 390, 410, 449, 469, 473, 477, 479, 482, 483, 484, 496, 500, 501, 511, 519, 533, 534, 546, 553, 554, 558, 573, 574, 592, 593, 597, 601, 663, 666, 677, 684, 685, 689, 691, 696, 705, 714, 715, 725, 729, 737, 757, 759, 775, 811, 820, 825, 830, 835, 840, 897, 898, 900, 912, 914, 966, 969, 970, 981, 995, 997, 999, 1000, 1004, 1008, 1011, 1015, 1016, 1031, 1050, 1052, 1053, 1057, 1069, 1070, 1072, 1087, 1089, 1094, 1103, 1107, 1129, 1148, 1149, 1150, 1161, 1177, 1201, 1205, 1206, 1208, 1213, 1215, 1226, 1238, 1255, 1285, 1339, 1352a, 1400, 1594, 1597, 1604, 1622, 1717, 1717, 1728, 1731, 1736, 1740, 1742, 1772, 1855, 1858, 1922, 1938, 1941, 1956, 1972, 1992, 2111, 2119, 2140, 2141, 2236, 2353, 2376, 2380, 2390, 2409, 2420, 2423, 2425, 2457, 2479, 2483, 2502, 2534, 2540, 2558, 2568, 2584, 2600, 2624, 2627, 2631, 2633, 2645, 2646, 2658, 2660, 2665, 2670, 2696, 2699, 2724, 2761

266, 656, 668, 1334, 2499, 2578

18, 45, 53, 54, 66, 109, 155, 171, 182, 185, 190, 201, 214, 223, 232, 235, 243, 246, 290, 308, 316, 324, 358, 367, 369, 381, 386, 393, 394, 402, 404, 409, 412, 413, 414, 415, 417, 425, 426, 480, 492, 494, 498, 512, 521, 523, 540, 577, 578, 586, 588, 594, 600, 603, 604, 628, 633, 634, 644, 645, 648, 649, 680, 686, 690, 698, 718, 727, 730, 731, 734, 741, 758, 761, 762, 763, 764, 769, 781, 783, 784, 786, 789, 790, 794, 797, 798, 802, 806, 818, 819, 824, 833, 834, 836, 839, 845, 846, 848, 858, 864, 866a, 867, 889, 890, 904, 921, 928, 938, 951, 952, 953, 959, 960, 977, 978, 1020, 1023, 1032, 1033, 1036, 1061, 1062, 1075, 1099, 1100, 1119, 1121, 1185, 1189, 1196, 1234, 1235, 1236, 1248, 1249, 1252, 1254, 1283, 1328, 1330, 1331, 1345, 1350b, 1356, 1377, 1395, 1445, 1447, 1476, 1492, 1503, 1504, 1516, 1543, 1547, 1548, 1572, 1577, 1605, 1613, 1614, 1619, 1637, 1723, 1725, 1726, 1732, 1733, 1741, 1746, 1747, 1761, 1762, 1771, 1856, 1859, 1899, 1902, 1918, 1928, 1929, 1952, 1975, 2085, 2160, 2261, 2266, 2273, 2303, 2309, 2310, 2355, 2356, 2406, 2407, 2431, 2441, 2454, 2466, 2484, 2503, 2593, 2626, 2629, 2634, 2651, 2653, 2666, 2668, 2679, 2698, 2716, 2765, 2767, 2773, 2774, 2775, 2780, 2783

30, 47, 58, 70, 149, 285, 286, 287, 288, 313, 368, 373, 379, 380, 385, 418, 432, 446, 448, 493, 525, 541, 575, 616, 664, 694, 739, 801, 841, 844, 853, 880, 955, 958, 961, 962, 1003, 1017, 1018, 1024, 1026, 1059, 1060, 1105, 1202, 1232, 1233, 1247, 1250, 1260, 1264, 1482, 1508, 1617, 1626, 1628, 1636, 1649, 1656, 1745, 1750, 1757, 1763, 1767, 1876, 1882, 1948, 1957, 1958, 1964, 1978, 2003, 2175, 2178, 2221, 2352, 2418, 2452, 2455, 2554, 2673, 2675, 2691, 2704, 2729

99, 1367

90, 335, 445, 724, 745, 755, 867, 957, 1019, 1030, 1065, 1068, 1088, 1239, 1362, 1370, 1374, 1618, 1749, 1768, 1861, 1883, 1911, 1930, 1931, 1936, 1937, 1979, 2009, 2218, 2378, 2422, 2496, 2501, 2532, 2555, 2572, 2573, 2579, 2635, 2636, 2690, 2711, 2721, 2779

1371

289, 868, 956, 963, 988, 1044, 1063, 1101, 1104, 1303, 1748, 1869, 2267, 2450, 2497, 2581, 2619, 2656.[20] CharacteristicsCompared to Alexandrian text-type manuscripts, the distinct Byzantine readings tend to show a greater tendency toward smooth and well-formed Greek, they display fewer instances of textual variation between parallel Synoptic Gospel passages, and they are less likely to present contradictory or "difficult" issues of exegesis.[21] Textus Receptus and Majority Text

The first printed edition of the Greek New Testament was completed by Erasmus and published by Johann Froben of Basel on March 1, 1516 (Novum Instrumentum omne).[13]: 143 Erasmus provided substantial scholarly annotations based on multiple Greek manuscripts and Patristic evidence, but produced a Greek text on around a half-dozen manuscripts, all of which dated from the twelfth century or later; and all but one were of the Byzantine text-type.[13]: 143–146 Six verses that were not witnessed in any of these sources, he initially back-translated from the Latin Vulgate; he also introduced some readings from the Caesarean text-type, Vulgate and Church Fathers.[13]: 143–146 [22] This text came to be known as the Textus Receptus or received text after being thus termed by Bonaventura Elzevir, an enterprising publisher from the Netherlands, in his 1633 edition of Erasmus' text.[13]: 152 The New Testament of the King James Version of the Bible was translated from editions of what was to become the Textus Receptus.[13]: 152 The different Byzantine "Majority Text" of Hodges & Farstad as well as Robinson & Pierpont is called "Majority" because it is considered to be the Greek text established on the basis of the reading found in the vast majority of the Greek manuscripts. Although the Textus Receptus may be considered a late Byzantine text, it still differs from the Majority Text of Robinson and Pierpont in 1,838 Greek readings, of which 1,005 represent "translatable" differences. Most of these variants are minor; however, the Byzantine text excludes the Comma Johannium and Acts 8:37, which are present in the Textus Receptus. Despite these differences, the RP Byzantine text agrees far more closely with the Textus Receptus than with the critical text, as the Majority Text disagrees with the critical text 6,577 times in contrast to the 1800 times it disagrees with the Textus Receptus. Additionally, many of the agreements between the Textus Receptus and the Byzantine text are considered very significant, such as the reading "God" in 1 Timothy 3:16 and the inclusion of the Story of the Adulteress.[23][24][13]: 145 Modern critical textsTextual critic and biblical scholar Karl Lachmann was the first scholar to produce an edition that broke with the Textus Receptus, ignoring previous printings and basing his text on ancient sources, therefore discounting the mass of late Byzantine manuscripts and the Textus Receptus.[25]: 21 The critical Greek New Testament texts of today (represented by UBS/NA Greek New Testaments) are considered to be predominantly representative of the Alexandrian text-type in nature,[26] but there are some critics such as Robinson and Hodges who still favor the Byzantine Text, and have produced Byzantine-Majority critical editions of the Greek New Testament.[7] Around 6,500 readings differ between the Majority text and the modern critical text (represented by UBS/NA Greek New Testaments), although the two still agree 98% of the time.[27] A critical edition of Family 35 of the Byzantine text has also been created by Wilbur N Pickering, who believes that Family 35 most accurately reflects the original text of the New Testament.[28] The Byzantine type is also found in modern Greek Orthodox editions. A new scholarly edition of the Byzantine Text of John's gospel, (funded by the United Bible Societies in response to a request from Eastern Orthodox Scholars), was begun in Birmingham, UK. and in 2007, as a result of these efforts, The Gospel According to John in the Byzantine Tradition was published.[6] Textual critic Herman von Soden divided manuscripts of the Byzantine text into five groups:

Since the discovery of 𝔓45, 𝔓46, and 𝔓66, these have demonstrated early manuscript witnesses to a small selection of Byzantine text readings.[30]: 55–61 [31]: 38 Examples: Luke 10:39 Luke 10:42

Luke 11:33 John 10:29 John 11:32 John 13:26 Acts 17:13 1 Corinthians 9:7 Ephesians 5:9 Philippians 1:14 Other examples of Byzantine readings were found in 𝔓66 in John 1:32; 3:24; 4:14, 51; 5:8; 6:10, 57; 7:3, 39; 8:41, 51, 55; 9:23; 10:38; 12:36; and 14:17.[31]: 38 fn. 2 Many of these readings have substantial support from other text-types and they are not distinctively Byzantine. Daniel Wallace found only two agreements distinctively between papyrus and Byzantine readings.[4]: 303 These readings support the views of scholars such as Harry Sturz (1984) and Maurice Robinson (2005) that the roots of the Byzantine text may go back to a very early date,[30]: 62–65 which some authors have interpreted as a rehabilitation of the Textus Receptus.[34] However in 1963 Bruce Metzger had argued that early support for Byzantine readings could not be taken to demonstrate that they were in the original text.[31]: 38 Modern translationsThe Byzantine majority text of Robinson and Pierpont is the basis of the World English Bible.[35] And an interlinear translation of the Hodges-Farstad text has been made by Thomas Nelson.[36] The Holman Christian Standard Bible was initially planned to become an English translation of the Byzantine majority text, although because Arthur Farstad died just few months into the project, it shifted to the Critical Text. However, the HCSB bible was still made to contain the Byzantine majority readings within its footnotes. Similarly, the New King James Version contains the Byzantine majority readings within the footnotes, although it is a translation of the Textus Receptus.[37] There also exists multiple translations of the Aramaic Peshitta into English, translations have been made by John W. Etheridge, James Murdock and George M. Lamsa.[38][39][40] The Peshitta has also been translated into Spanish[41] and into Malayam.[42] An English translation of Family 35 has also been created by Wilbur Pickering, called "The Sovereign Creator Has Spoken" translation.[43] See alsoFamilies of the Byzantine text-type

Other text-types

Critical textNotes

Further reading

External links

|