1912 New York City waiters' strike

| |||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Artikel ini perlu diterjemahkan dari bahasa Inggris ke bahasa Indonesia. Artikel ini ditulis atau diterjemahkan secara buruk dari Wikipedia bahasa Inggris. Jika halaman ini ditujukan untuk komunitas bahasa Inggris, halaman itu harus dikontribusikan ke Wikipedia bahasa Inggris. Lihat daftar bahasa Wikipedia. Artikel yang tidak diterjemahkan dapat dihapus secara cepat sesuai kriteria A2. Jika Anda ingin memeriksa artikel ini, Anda boleh menggunakan mesin penerjemah. Namun ingat, mohon tidak men...

Ilmu-ilmu alam mengalami berbagai kemajuan pada masa Zaman Kejayaan Islam.[1] Selama periode ini, teologi Islam mendorong para pemikir untuk mencari ilmu pengetahuan.[2] para pemikir dari periode ini termasuk Al-Farabi, Abu Bishr Matta, Ibnu Sina, al-Hassan Ibnu al-Haitham, dan Ibnu Bajjah.[3] Studi akademis Islam dalam ilmu pengetahuan telah mewarisi . Penggunaan pengamatan empiris membawa kepada pembentukan bentuk sederhana dari metode ilmiah.[4] Studi fisika...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (مارس 2016) مصر في الألعاب الأولمبية علم مصر رمز ل.أ.د. EGY ل.أ.و. اللجنة الأولمبية المصرية موقع الويبwww.egyptianolymp...

United States historic placeReo Motor Car Company PlantFormerly listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic PlacesFormer U.S. National Historic Landmark Reo clubhouse, factory, and engineering building, 1977Location2100 S. Washington St., Lansing, MichiganArea16.5 acres (6.7 ha)Built1904 (1904)Built byRansom E. OldsNRHP reference No.78001500[1]Significant datesAdded to NRHPJune 2, 1978Removed from NRHPMarch 5, 1986 The Reo Motor Car Company Plant was...

Abrar Alviअबरार अलवीابرار علویdi apartemennya di Mumbai dengan cucu keponakan perempuan Fizaa Dosani pada tahun 2007.Lahir1 Juli 1927Meninggal18 November 2009lokhandwala andher(w) mumbaiPekerjaanSutradara filmTahun aktif1954–1995 Abrar Alvi (Hindi: अबरार अलवी; bahasa Urdu: ابرار علوی; 1927 – 18 November 2009) adalah seorang aktor, sutradara, dan penulis film India. Kebanyakan karya terkenalnya berasal dari 1950an dan 1960...

Hospital in Cairo Governorate, EgyptChildren Cancer Hospital EgyptAFNCIGeographyLocationZeinhom, El-Sayeda Zainab, Cairo Governorate, EgyptCoordinates30°01′22″N 31°14′16″E / 30.022715°N 31.237870°E / 30.022715; 31.237870OrganisationFundingNon-profit hospitalTypeSpecialistServicesBeds320SpecialityChildren's cancerHistoryOpened2007LinksWebsitewww.57357.orgListsHospitals in Egypt Children's Cancer Hospital Egypt, also known as 57357 hospital after the hospital...

135/45 Modello 1937/1938Le torri prodiere dello ScipioneTipocannone navale ImpiegoUtilizzatori Regia Marina Marina Militare ProduzioneCostruttoreAnsaldoOdero-Terni-Orlando Entrata in servizio1940 Ritiro dal servizio1972 DescrizionePesoTorri:Mod. 1937: 103,3 tMod. 1938: 41,3 t Lunghezza canna5.142m Calibro135 mm (5,3 inch) Peso proiettile32.7 kg Velocità alla volata825 m/s Gittata massima19,6 Km(ad una elevazione di 45°) Elevazione-5°/+45° navweaps voci di ...

Questa voce sugli argomenti allenatori di pallacanestro statunitensi e cestisti statunitensi è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti dei progetti di riferimento 1, 2. Dave Henderson Dave Henderson (a destra) con la maglia di Duke Nazionalità Stati Uniti Altezza 196 cm Peso 88 kg Pallacanestro Ruolo PlaymakerAllenatore Termine carriera 1998 - giocatore2006 - allenatore CarrieraGiovanili Warren County High School1982-...

Северный морской котик Самец Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:Синапси...

周處除三害The Pig, The Snake and The Pigeon正式版海報基本资料导演黃精甫监制李烈黃江豐動作指導洪昰顥编剧黃精甫主演阮經天袁富華陳以文王淨李李仁謝瓊煖配乐盧律銘林孝親林思妤保卜摄影王金城剪辑黃精甫林雍益制片商一種態度電影股份有限公司片长134分鐘产地 臺灣语言國語粵語台語上映及发行上映日期 2023年10月6日 (2023-10-06)(台灣) 2023年11月2日 (2023-11-02)(香�...

Voce principale: Cuneo Granda Volley. Cuneo Granda VolleyStagione 2023-2024Sport pallavolo Squadra Cuneo Granda Allenatore Massimo Bellano, poi Stefano Micoli All. in seconda Emanuele Aime Presidente Patrizio Bianco, Emilio Manini Serie A113ª Maggiori presenzeCampionato: Signorile, Stigrot, Sylves (26)Totale: Signorile, Stigrot, Sylves (26) Miglior marcatoreCampionato: Stigrot (298)Totale: Stigrot (298) 2022-23 2024-25 Questa voce raccoglie le informazioni riguardanti la Cuneo Granda V...

Folly in WentworthKeppel's ColumnKeppel's ColumnTypeFollyLocationWentworthCoordinates53°26′53″N 1°24′55″W / 53.447931°N 1.415144°W / 53.447931; -1.415144OS grid referenceSK 38941 94731AreaSouth YorkshireBuilt1773-1780ArchitectJohn Carr Listed Building – Grade II*Official nameKeppels ColumnDesignated19 February 1986Reference no.1314632 Location of Keppel's Column in South Yorkshire Keppel's Column is a 115-foot (35 m)[1][2 ...

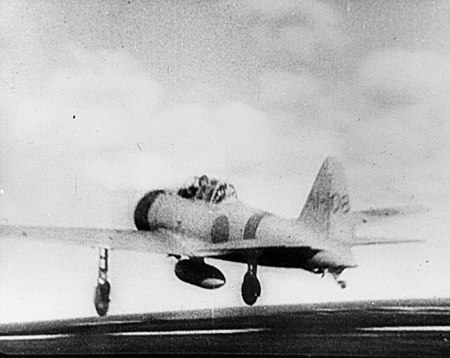

WWII battle in Ceylon between Britain and Japan This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Easter Sunday Raid – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Easter Sunday Raid on CeylonPart of the Pacific Theatre of World War IIDate5 April 1942Loca...

Journalist for Los Angeles Times William Tuohy William Bill Tuohy (October 1, 1926 – December 31, 2009) was a journalist and author who, for most of his career, was a foreign correspondent for the Los Angeles Times.[1][2] Early life Tuohy was born on October 1, 1926, in Chicago, Illinois, and was brought up in that city. In 1945 he joined the U.S. Navy, and served for two years aboard a submarine rescue vessel, USS Florikan, in the Pacific.[3] In 1947, and a...

Jewelry worn around the wrist For other uses, see Bracelet (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Bracelet – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) A decorative gold charm bracelet showing a heart-shaped locket, seahor...

Sporting event delegationAruba at thePan American GamesFlag of ArubaIOC codeARUNOCAruban Olympic CommitteeWebsitewww.olympicaruba.comMedalsRanked 42nd Gold 0 Silver 2 Bronze 2 Total 4 Pan American Games appearances (overview)1987199119951999200320072011201520192023Other related appearances Netherlands Antilles (1987–) Aruba has competed at every edition of the Pan American Games since the tenth edition of the multi-sport event in 1987. Aruba did not compete at the first and only Pan Am...

Comprehensive physical model Grand Unification redirects here. For the albums, see Grand Unification (Fightstar album) and Grand Unification (Milford Graves album). Beyond the Standard ModelSimulated Large Hadron Collider CMS particle detector data depicting a Higgs boson produced by colliding protons decaying into hadron jets and electrons Standard Model Evidence Hierarchy problem Dark matter Dark energy Quintessence Phantom energy Dark radiation Dark photon Cosmological constant problem Str...

The Metelko alphabet (Slovene: metelčica) was a Slovene writing system developed by Franc Serafin Metelko. It was used by a small group of authors from 1825 to 1833 but it was never generally accepted. Example of the Metelko alphabet: Valentin Stanič's adaptation of the poem Der Kaiser und der Abt by Gottfried August Bürger South Slavic languages and dialects Western South Slavic Serbo-Croatian Standard languages Bosnian Croatian Montenegrin Serbian(Slavonic-Serbian) Dialects Shtokavian (Y...

В этой статье описывается запланированный или строящийся, но ещё не построенный объект или здание.Информация может меняться по мере поступления новых данных о ходе строительства. Центральный мост 55°00′32″ с. ш. 82°55′12″ в. д.HGЯO Официальное название Центральн...

Suchoi Su-30 Suchoi Su-30MKA der algerischen Luftwaffe Typ * Langstreckenabfangjäger Mehrzweckkampfflugzeug Entwurfsland Russland Russland (Sowjetunion Sowjetunion) Hersteller Suchoi Erstflug 30. Dezember 1989 Indienststellung 14. April 1992 Produktionszeit Seit 1991 in Serienproduktion Stückzahl 612+[1][2] Die Suchoi Su-30 (russisch Сухой Су-30, NATO-Codename: Flanker-C) ist ein russisches Mehrzweckkampfflugzeug auf der Basis des zweisitzigen Trainingsflugz...