When Tomorrow Comes (film)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Alesheim. Alesheim adalah kota yang terletak di distrik Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen di Bavaria, Jerman. Kota Alesheim memiliki luas sebesar 20.45 km² . Alesheim pada tahun 2006, memiliki penduduk sebanyak 1.020 jiwa. lbsKota dan kotamadya di Weissenburg-GunzenhausenAbsberg | Alesheim | Bergen | Burgsalach | Dittenheim | Ellingen | Ettenstatt | Gnotzheim | Gunzenhausen | Haundorf | Heidenheim | Höttingen | Langenaltheim | Mar...

Ked-Air merupakan sebuah maskapai penerbangan yang berbasis di Alor Star, Kedah, Malaysia. Maskapai ini mengoperasikan penerbangan domestik.[1] Sejarah Maskapai penerbangan ini diresmikan pada Januari 2004 dan memulai operasinya pada 20 Januari 2004.[1] Maskapai ini juga berusaha membeli maskapai penerbangan tua milik Malaysia, Pelangi Air.[2] Penerbangan Ked-Air mengoperasikan penerbangan antara Alor Star dan Medan, Indonesia.[1] Bagaimanapun, pada tahun 2006,...

Mei NaganoNama asal永野 芽郁Lahir24 September 1999 (umur 24)Tokyo, JepangPekerjaanAktris, PeragawatiTahun aktif2009–sekarangAgenStardust PromotionSitus webProfil Mei Nagano (永野 芽郁code: ja is deprecated , Nagano Mei, kelahiran 24 September 1999 di Tokyo, Jepang) adalah seorang aktris dan model Jepang. Drama televisi Yae no Sakura (NHK, 2013), sebagai Tokiwa Yamakawa[1] Itsuka Kono Koi o Omoidashite Kitto Naite Shimau (Fuji TV, 2016), sebagai Remi Funakawa&...

Metallic brown resembling the alloy bronze This article is about the colour. For other uses, see Bronze (disambiguation). Bronze Color coordinatesHex triplet#CD7F32sRGBB (r, g, b)(205, 127, 50)HSV (h, s, v)(30°, 76%, 80%)CIELChuv (L, C, h)(60, 81, 39°)Source[1]/Maerz and Paul[1]ISCC–NBS descriptorStrong orangeB: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) Bronze statue of the Roman Emperor Augustus Bronze is a metallic brown colour which resembles the metal alloy bronze...

City in Tehran province, Iran For the administrative divisions, see Pishva County and Pishva Rural District. City in Tehran, IranPishva Persian: پيشواCityThe city of PishvaPishvaCoordinates: 35°18′24″N 51°43′14″E / 35.30667°N 51.72056°E / 35.30667; 51.72056[1]CountryIranProvinceTehranCountyPishvaDistrictCentralElevation937 m (3,074 ft)Population (2016)[2] • Total59,184Time zoneUTC+3:30 (IRST) Historical Popula...

Jari Litmanen Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Jari Olavi LitmanenTanggal lahir 20 Februari 1971 (umur 53)Tempat lahir Hollola, FinlandiaTinggi 1,82 m (5 ft 11+1⁄2 in)Posisi bermain StrikerAttacking midfielder Second strikerInformasi klubKlub saat ini FC LahtiNomor 10Karier junior1977–1987 ReipasKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol) 1987–1990 1991 1992 1992–1999 1999–2001 2001–2002 2002–2004 2004 2005 2005–2007 2008 2008- Reipas HJK MyPa Ajax FC Barcelona ...

1931 film Not to be confused with The Easiest Way (1917 film). The Easiest WayOpening titlesDirected byJack ConwayWritten byEdith EllisBased onThe Easiest Way1909 playby Eugene WalterProduced byHunt StrombergStarringConstance BennettAdolphe MenjouRobert MontgomeryAnita Page Marjorie RambeauClark GableCinematographyJohn J. MescallEdited byFrank SullivanDistributed byMetro-Goldwyn-MayerRelease date February 7, 1931 (1931-02-07) Running time73 minutesCountryUnited StatesLanguageEn...

Gubernur Akademi MiliterLambang Akademi MiliterPetahanaMayjen. TNI R. Sidharta Wisnu Graha, S.E.sejak 17 Juli 2023TNI Angkatan DaratKantorMarkas Akademi Militer, Kota Magelang, Jawa TengahDibentuk31 Oktober 1945Pejabat pertamaMayjen TNI SoewardiSitus webwww.akmil.ac.id Gubernur Akademi Militer adalah pimpinan tertinggi Akademi Militer (Akmil), sekolah pendidikan TNI Angkatan Darat di Magelang, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia. Akademi Militer sebagai Badan Pelaksana Pusat di tingkat mabes TNI-AD, ...

Si ce bandeau n'est plus pertinent, retirez-le. Cliquez ici pour en savoir plus. Cet article ne cite pas suffisamment ses sources (septembre 2015). Si vous disposez d'ouvrages ou d'articles de référence ou si vous connaissez des sites web de qualité traitant du thème abordé ici, merci de compléter l'article en donnant les références utiles à sa vérifiabilité et en les liant à la section « Notes et références ». En pratique : Quelles sources sont attendues ?...

Cormicycomune Cormicy – Veduta LocalizzazioneStato Francia RegioneGrand Est Dipartimento Marna ArrondissementReims CantoneBourgogne TerritorioCoordinate49°22′N 3°54′E / 49.366667°N 3.9°E49.366667; 3.9 (Cormicy)Coordinate: 49°22′N 3°54′E / 49.366667°N 3.9°E49.366667; 3.9 (Cormicy) Superficie24,03 km² Abitanti1 445[1] (2009) Densità60,13 ab./km² Altre informazioniCod. postale51220 Fuso orarioUTC+1 Codice INSEE5...

Disambiguazione – Se stai cercando altri significati, vedi Romolo (disambigua). RomoloRomolo e suo fratello Remo da un fregio del XV secolo, Certosa di Pavia1º Re di RomaIn carica753 a.C.[1] –717 a.C.[2] Predecessorecarica creata SuccessoreNuma Pompilio[3][4] NascitaAlba Longa, 24 marzo 771 a.C.[1] MorteRoma, 5[5] o 7 luglio 716 a.C.[2] Casa realedi Alba Longa DinastiaRe latino-sabini PadreMarte[1][6][...

Дело «Запасного правотроцкистского центра контрреволюционной националистической организации» (ЗПЦКНО) (азерб. “Sağ-trotskiçi ehtiyat mərkəzinin əksinqilabi milliyətçi təşkilatı” rəhbərlərinin işi, 1938-1956) — сфабрикованное высшим руководством Азербайджанской ССР политическое дело, по которому было...

American college football season For the FCS season contested during fall 2020/spring 2021, see 2020–21 NCAA Division I FCS football season. 2021 NCAA Division I FCS seasonRegular seasonNumber of teams128DurationAugust 28 – November 27Payton AwardEric Barriere, QB, Eastern WashingtonBuchanan AwardIsaiah Land, DL, Florida A&MPlayoffDurationNovember 27 – December 18Championship dateJanuary 8, 2022Championship siteToyota Stadium, Frisco, TexasChampionNorth Dakota StateNCAA Division I F...

Сельское поселение России (МО 2-го уровня)Новотитаровское сельское поселение Флаг[d] Герб 45°14′09″ с. ш. 38°58′16″ в. д.HGЯO Страна Россия Субъект РФ Краснодарский край Район Динской Включает 4 населённых пункта Адм. центр Новотитаровская Глава сельского пос�...

Laut JawaLokasi Laut JawaLaut JawaLetakPaparan SundaKoordinat5°16′00″S 111°43′52″E / 5.26667°S 111.73111°E / -5.26667; 111.73111Jenis perairanLautTerletak di negaraIndonesiaPanjang maksimal1.600 kilometer (990 mi)Lebar maksimal380 kilometer (240 mi)Area permukaan320.000 kilometer persegi (120.000 sq mi)Kedalaman rata-rata46 meter (151 ft)Suhu tertinggi31 °C (88 °F)Suhu terendah27 °C (81 °F)KepulauanSunda besa...

Dacre MontgomeryMontgomery di San Diego Comic-Con 2017LahirDacre Montgomery22 November 1994 (umur 29)Perth, Australia BaratAlmamaterUniversitas Edith Cowan (BA)PekerjaanAktorTahun aktif2011–sekarang Dacre Montgomery (lahir 22 November 1994) adalah seorang aktor asal Australia. Dia terkenal karena perannya sebagai Jason Scott, Red Ranger di film Power Rangers;[1] dan Billy Hargrove di musim kedua Stranger Things. Kehidupan Awal Montgomery lahir di Perth, Australia Barat da...

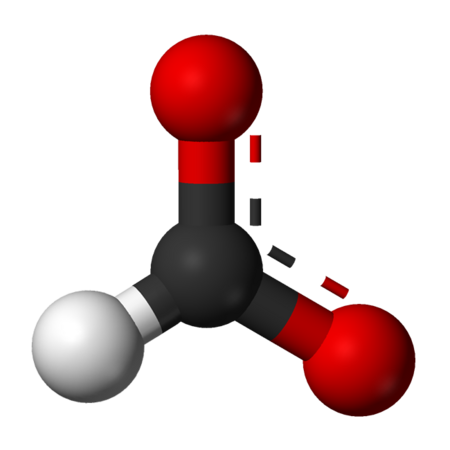

Potassium formate[1] Names Preferred IUPAC name Potassium formate Identifiers CAS Number 590-29-4 Y 3D model (JSmol) Interactive image ChemSpider 11054 N ECHA InfoCard 100.008.799 PubChem CID 11539 UNII 25I90B156L Y CompTox Dashboard (EPA) DTXSID6029626 InChI InChI=1S/CH2O2.K/c2-1-3;/h1H,(H,2,3);/q;+1/p-1 NKey: WFIZEGIEIOHZCP-UHFFFAOYSA-M NInChI=1/CH2O2.K/c2-1-3;/h1H,(H,2,3);/q;+1/p-1Key: WFIZEGIEIOHZCP-REWHXWOFAK SMILES C(=O)[O-].[K+] Properties Ch...

Renewable energy made from biomass This article is about technology aspects to produce a type of renewable energy. For production of biomass for bioenergy generation, see biomass (energy). This article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. Please improve the article by adding information on neglected viewpoints, or discuss the issue on the talk page. (May 2023) Sugarcane plantation to produce ethanol in BrazilA CHP power station using wood to supply 30,000 households in France Bioenerg...

Monte BondoneLa cima Palon del monte Bondone visto da GiovoStato Italia Regione Trentino-Alto Adige Provincia Trento ComuneTrento, Vallelaghi, Madruzzo, Cavedine, Garniga, Cimone Altezza2 180 m s.l.m. Prominenza1 679 m Isolamento16,48 km CatenaAlpi Coordinate45°59′17″N 11°01′51″E45°59′17″N, 11°01′51″E Altri nomi e significatiMontagna di TrentoBondon (dialetto locale) Mappa di localizzazioneMonte Bondone Dati SOIUSAGrande ParteAlpi Or...

الأشمونين - قرية مصرية - تقسيم إداري البلد مصر[1] التقسيم الأعلى مركز ملوي المسؤولون خصائص جغرافية إحداثيات 27°46′28″N 30°48′04″E / 27.774438888889°N 30.801111111111°E / 27.774438888889; 30.801111111111 الارتفاع 44 متر[2] معلومات أخرى التوقيت ت ع م+02:00 الرمز...