The Woman on Pier 13

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Konstantinus VIΚωνσταντῖνος Ϛ΄Konstantinus VI (sebelah kanan salib) memimpin Konsili Nicea II. Miniatur dari awal abad kesebelas.Kaisar Romawi TimurBerkuasa8 September 780 – Agustus 797PendahuluLeo IVPenerusIreneWaliIreneInformasi pribadiKelahiran771Kematiansebelum 805WangsaDinasti IsaurianusAyahLeo IV, Kaisar Romawi TimurIbuIrene, Maharani Romawi TimurPasanganMaria dari AmniaTheodoteAnakEuphrosyneIreneLeo Konstantinus VI (bahasa Yunani Kuno: Κωνσταντῖνος Ϛ�...

Pour la dernière participation de la France, voir France au Concours Eurovision de la chanson 2023. Pour les participations aux éditions junior du concours, voir France au Concours Eurovision de la chanson junior. France au Concours Eurovision Pays France Radiodiffuseur Finales :1956–64 : RTF1965–74 : ORTF 1re1975–81 : TF11983–92 : Antenne 21993–98 : France 21999–2014 : France 3depuis 2015 : France 2Demi-finales :2005-2010 ...

Stand-up roller coaster For the episode of the animated television series 'The Batman', see Riddler's Revenge (The Batman). For the pendulum ride at Six Flags Over Texas, see The Riddler Revenge. The Riddler's RevengeThe chain lift hill and vertical loop of Riddler's RevengeSix Flags Magic MountainLocationSix Flags Magic MountainPark sectionMetropolisCoordinates34°25′28″N 118°36′02″W / 34.424524°N 118.600637°W / 34.424524; -118.600637StatusOperatingSoft ope...

Bagian dari serial artikel mengenaie Artikel mengenai e 2.718 281 828 459 045 235 360 287 … {\displaystyle 2.718\,281\,828\,459\,045\,235\,360\,287\dots } Penggunaan Bunga majemuk Identitas Euler Rumus Euler Waktu paruh (pertumbuhan dan peluruhan eksponensial) Sifat Logaritma alami Fungsi eksponensial Nilai Bukti bahwa e irasional Representasi dari e Teorema Lindemann-Weierstrass Tokoh John Napier Leonhard Euler Topik terkait Konjektur Schanuel Portal Matematikalbs Identitas Euler[...

Department in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France This article is about the French department. For other uses, see Allier (disambiguation). Department in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, FranceAllier Alèir (Occitan)DepartmentPrefecture building in Moulins FlagCoat of armsLocation of Allier in FranceCoordinates: 46°20′N 3°10′E / 46.333°N 3.167°E / 46.333; 3.167CountryFranceRegionAuvergne-Rhône-AlpesPrefectureMoulinsSubprefecturesMontluçonVichyGovernment • Pr...

العلاقات الألبانية البوتانية ألبانيا بوتان ألبانيا بوتان تعديل مصدري - تعديل العلاقات الألبانية البوتانية هي العلاقات الثنائية التي تجمع بين ألبانيا وبوتان.[1][2][3][4][5] مقارنة بين البلدين هذه مقارنة عامة ومرجعية للدولتين: وجه المقارنة...

Papa Vittore I14º papa della Chiesa cattolicaElezione189 Fine pontificato199 Predecessorepapa Eleuterio Successorepapa Zefirino NascitaAfrica Proconsolare, II secolo MorteRoma, 28 luglio 199[1] SepolturaNecropoli vaticana Manuale San Vittore I Papa e martire NascitaAfrica Proconsolare, II secolo MorteRoma, 28 luglio 199 Venerato daTutte le Chiese che ammettono il culto dei santi Santuario principaleBasilica di San Pietro in Vaticano Ricorrenza28 luglio Manuale Vittor...

Pyramis GroupCompany typePublic (S.A.)IndustryKitchen Fixtures Kitchen AppliancesFounded1959FounderAlexandros Bakatselos[1]HeadquartersThessaloniki, GreeceKey peopleNikolaos Bakatselos (President & CEO)[2]ProductsStainless Steel SinksComposite SinksFaucetsKitchen AppliancesRevenue€65.035 million (2016)[3]Operating income€13.811 million (2016)[4]Net income€229.551 thousand (2016)[5]Total assets€66.085 million (2016)[6]Total equity€5...

Wine making in Hungary Hungarian wine has a history dating back to the Kingdom of Hungary. Outside Hungary, the best-known wines are the white dessert wine Tokaji aszú (particularly in the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia) and the red wine Bull's Blood of Eger (Egri Bikavér). Etymology The Hungarian word for wine bor is of Eastern origin Only three European languages have words for wine that are not derived from Latin: Greek, Basque, and Hungarian.[1] The Hungarian word for wine...

Outdated grouping of human beings The Mediterranean race (also Mediterranid race) is an obsolete racial classification of humans based on a now-disproven theory of biological race.[1][2][3] According to writers of the late 19th to mid-20th centuries it was a sub-race of the Caucasian race.[4] According to various definitions, it was said to be prevalent in the Mediterranean Basin and areas near the Mediterranean, especially in Southern Europe, North Africa, mos...

La bella e la bestiaLogo originale del filmTitolo originaleLa Belle et la Bête Lingua originalefrancese Paese di produzioneFrancia, Germania Anno2014 Durata112 min Rapporto2,35:1 Generefantastico, sentimentale, drammatico RegiaChristophe Gans SoggettoLa bella e la bestia SceneggiaturaChristophe Gans, Sandra Vo-Anh ProduttoreRichard Grandpierre Produttore esecutivoFrédéric Doniguian Casa di produzionePathé, Eskwad, Studio Babelsberg Distribuzione in italianoNotorious Pictures F...

В Википедии есть статьи о других людях с фамилией Глущенко. Галина Евдокимовна Глущенко Дата рождения 17 ноября 1930(1930-11-17) Место рождения село Кошаринцы, Бершадский район Винницкая область Дата смерти 14 апреля 2014(2014-04-14) (83 года) Место смерти Киев, Украина Гражданство &#...

Державний комітет телебачення і радіомовлення України (Держкомтелерадіо) Приміщення комітетуЗагальна інформаціяКраїна УкраїнаДата створення 2003Керівне відомство Кабінет Міністрів УкраїниРічний бюджет 1 964 898 500 ₴[1]Голова Олег НаливайкоПідвідомчі ор...

本條目存在以下問題,請協助改善本條目或在討論頁針對議題發表看法。 此條目需要編修,以確保文法、用詞、语气、格式、標點等使用恰当。 (2013年8月6日)請按照校對指引,幫助编辑這個條目。(幫助、討論) 此條目剧情、虛構用語或人物介紹过长过细,需清理无关故事主轴的细节、用語和角色介紹。 (2020年10月6日)劇情、用語和人物介紹都只是用於了解故事主軸,輔助�...

Ne doit pas être confondu avec Luge d'été. Pour les articles homonymes, voir Luge. Cet article est une ébauche concernant une attraction ou le domaine des attractions. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Consultez la liste des tâches à accomplir en page de discussion. Eifel-Coaster d'Eifelpark, Allemagne Trapper Slider à Fort Fun Abenteuerland, Allemagne Les luges sur rail (parfois désignées...

1998 book by Michael Breen The Koreans First editionAuthorMichael BreenCountryUnited KingdomLanguageEnglishGenreNon-fictionPublisherThomas Dunne BooksPublication date1998Media typePrint (Hardback & Paperback)Pages304ISBN0-312-24211-5 The Koreans: Who They Are, What They Want, Where Their Future Lies is a 1998 non-fiction book by British journalist Michael Breen. It was first published in 1998 by Thomas Dunne Books. Later, Breen authored The New Koreans: The Story of a Nation.[1&#...

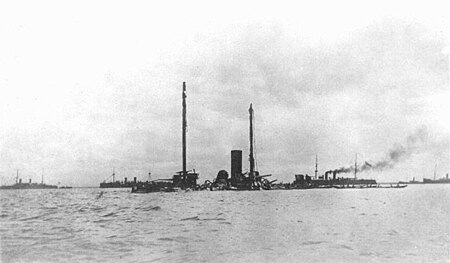

Castila History Spain NameCastilla NamesakeCastile, an historical region of Spain Ordered1869 BuilderLa Carraca shipyard, Cadiz, Spain Laid downMay 1869 LaunchedAugust 1881[2] Completed1881 or 1882[1] Commissioned1882 FateSunk 1 May 1898 General characteristics Class and typeAragon-class unprotected cruiser Displacement3,289 tons Length236 ft 0 in (71.93 m) Beam44 ft 0 in (13.41 m) Draft23 ft 6 in (7.16 m) maximum Installed po...

German-American piano maker This article is about the founder of the piano company Steinway & Sons. For his great-grandson, see Henry Z. Steinway. Henry E. SteinwayHenry E. Steinway. This studio photo was taken by Mathew Brady, a noted Civil War-era photographer.BornHeinrich Engelhard Steinweg(1797-02-22)February 22, 1797Wolfshagen im Harz,[1] Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Holy Roman Empire(now Langelsheim, Lower Saxony, Germany)DiedFebruary 7, 1871(1871-02-07) (aged 73)New York, ...

Climatic conditions of Minnesota, US Köppen climate types of Minnesota, using 1991-2020 climate normals. Minnesota has a humid continental climate, with hot summers and cold winters. Minnesota's location in the Upper Midwest allows it to experience some of the widest variety of weather in the United States, with each of the four seasons having its own distinct characteristics. The area near Lake Superior in the Minnesota Arrowhead region experiences weather unique from the rest of the state....

Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung— BMBF — Logo Staatliche Ebene Bund Stellung oberste Bundesbehörde Geschäftsbereich Gemeinsam mit den Ländern kümmert sich das BMBF um die außerschulische berufliche Bildung, die Aufstiegsförderung und die berufliche Weiterbildung.[1] Gründung 20. Oktober 1955 als Bundesministerium für Atomfragen[2] Hauptsitz Bonn,Nordrhein-Westfalen Nordrhein-Westfalen Behördenleitung Bettina Stark-Watzinger (FDP), Bundesministeri...