St John the Baptist's Church, Chester

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

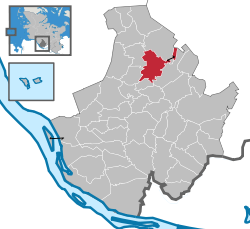

Barmstedt Lambang kebesaranLetak Barmstedt di Pinneberg NegaraJermanNegara bagianSchleswig-HolsteinKreisPinneberg Pemerintahan • MayorNils HammermannLuas • Total17,17 km2 (663 sq mi)Ketinggian11 m (36 ft)Populasi (2013-12-31)[1] • Total10.068 • Kepadatan5,9/km2 (15/sq mi)Zona waktuWET/WMPET (UTC+1/+2)Kode pos25355Kode area telepon04123Pelat kendaraanPISitus webwww.barmstedt.de Barmstedt adalah kota yang...

Book by Jorge Luis Borges This article relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this article by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: Historia de la eternidad – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Historia de la eternidad First editionAuthorJorge Luis BorgesCountryArgentinaLanguageSpanishGenreessayPublished1936, Viau y Zona (Buenos Aires...

While New York SleepsSebuah poster dari sebuah surat kabar.SutradaraCharles BrabinProduserWilliam FoxDitulis olehCharles BrabinThomas FallonSinematograferGeorge W. LaneBennie MigginsDistributorFox Film CorporationTanggal rilis Desember 1920 (1920-12) Durasi8 rolNegaraAmerika SerikatBahasaBisu (intertitel Inggris) While New York Sleeps adalah sebuah film drama kejahatan Amerika Serikat tahun 1920 yang diproduksi oleh Fox Film Corporation dan disutradarai oleh Charles Brabin, yang merupaka...

Katedral BeaumontKatedral Basilika Santo AntoniusInggris: St. Anthony Cathedral Basilicacode: en is deprecated Katedral Beaumont30°04′40″N 94°06′03″W / 30.0777°N 94.1009°W / 30.0777; -94.1009Koordinat: 30°04′40″N 94°06′03″W / 30.0777°N 94.1009°W / 30.0777; -94.1009Lokasi700 Jefferson St.Beaumont, TexasNegaraAmerika SerikatDenominasiGereja Katolik RomaSitus webwww.stanthonycathedral.orgSejarahDedikasiAntonius dari PaduaTan...

Fernando Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Fernando Lucas MartinsTanggal lahir 3 Maret 1992 (umur 32)Tempat lahir Erechim, BrazilTinggi 1,74 m (5 ft 8+1⁄2 in)Posisi bermain Defensive MidfielderInformasi klubKlub saat ini Shakhtar DonetskNomor TBDKarier junior2001–2010 GrêmioKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2010–2013 Grêmio 68 (2)2013– Shakhtar Donetsk 0 (0)Tim nasional‡2009 Brazil U17 3 (0)2011 Brazil U20 15 (0)2012– Brazil 7 (0) * Penampilan dan gol di k...

Gambar lintasan Grand Prix Sepeda Motor Ceko (Inggris Czech Republic motorcycle Grand Prix) adalah acara balap motor yang menjadi bagian dari Grand Prix Sepeda Motor. Sebelum tahun 1993, balapan ini dikenal dengan nama Czechoslovakian motorcycle Grand Prix. Sejak tahun 1963 menjadi bagian dari MotoGP (antara tahun 1982 dan 1987 lomba hanya diadakan seri European Grand Prix). Kombinasi sirkuit Masaryk (Sirkuit Brno) antara 1930 dan sekarang Sejak tahun 1987 lomba dilangsungkan di sirkuit baru ...

Bagian dari seriIlmu Pengetahuan Formal Logika Matematika Logika matematika Statistika matematika Ilmu komputer teoretis Teori permainan Teori keputusan Ilmu aktuaria Teori informasi Teori sistem FisikalFisika Fisika klasik Fisika modern Fisika terapan Fisika komputasi Fisika atom Fisika nuklir Fisika partikel Fisika eksperimental Fisika teori Fisika benda terkondensasi Mekanika Mekanika klasik Mekanika kuantum Mekanika kontinuum Rheologi Mekanika benda padat Mekanika fluida Fisika plasma Ter...

PT Yodya Karya (Persero)SebelumnyaPN Yodya Karya (1961 - 1972)JenisBadan usaha milik negaraIndustriKonsultansiPendahuluNV Architectenbureau Job en SpreyDidirikan29 Maret 1961; 63 tahun lalu (1961-03-29)KantorpusatJakarta, IndonesiaWilayah operasiIndonesiaTokohkunciColbert Thomas Pangaribuan[1](Direktur Utama)Zuhairi Misrawi[2](Komisaris Utama)JasaKonsultansi konstruksiKonsultansi non-konstruksiPengembangan propertiPenyusunan rancangan dan rekayasaPendapatanRp 334,008 mily...

Type of guipure bobbin lace from Malta Mikiel Farrugia, Young lace-making student at Casa Industriale, Xagħra, Gozo, c. 1895 Maltese lace (Maltese: bizzilla) is a style of bobbin lace made in Malta. It is a guipure style of lace. It is worked as a continuous width on a tall, thin, upright lace pillow. Bigger pieces are made of two or more parts sewn together. The Lace Pillow in Malta is known as Trajbu (pronounced as try-boo), while the Bobbins are called Ċombini (pronounced as chom-b...

QuittebeufcomuneQuittebeuf – Veduta LocalizzazioneStato Francia Regione Normandia Dipartimento Eure ArrondissementÉvreux CantoneLe Neubourg TerritorioCoordinate49°06′N 1°01′E / 49.1°N 1.016667°E49.1; 1.016667 (Quittebeuf)Coordinate: 49°06′N 1°01′E / 49.1°N 1.016667°E49.1; 1.016667 (Quittebeuf) Superficie13,36 km² Abitanti606[1] (2009) Densità45,36 ab./km² Altre informazioniCod. postale27110 Fuso orarioUTC+1 C...

Kazuhiko YamaguchiLahir5 Februari 1937 (umur 87)Prefektur NaganoPekerjaanSutradara film Kazuhiko Yamaguchi (山口和彦code: ja is deprecated , Yamaguchi Kazuhiko, lahir 5 Februari 1937) adalah seorang sutradara film Jepang.[1] Karier Kazuhiko lahir di Prefektur Nagano dan lulus dari Universitas Waseda. Ia mulai bekerja di studio Tōei di Kyoto.[2] Ia menyutradari sejumlah seri film laga pada tahun 1970-an dan juga beberapa film televisi.[2] Filmografi Delinquen...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento matematica non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Curve trasverse sulla superficie di una sfera Curve non trasverse sulla superficie di una sfera In matematica, e più precisamente in topologia differenziale, la trasversalità è una proprietà opposta alla ta...

This article is about the town in Poland. For the Polish police force, see Policja and Law enforcement in Poland. This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (February 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Place in West Pomeranian Voivodeship, PolandPoliceSaints Peter and Paul Gothic Church in Police-Jasienica FlagCoat of armsPoliceCoordinates:...

Satirical political map of North America Jesusland redirects here. For the Ben Folds song, see Jesusland (song).A recreation of the Jesusland map; the colors differ from the original, and state lines have been added United States of Canada: Canada, plus the blue states which voted for John Kerry in the 2004 United States presidential election Jesusland, the red states which voted for George W. Bush in the 2004 United States presidential election Some versions of the ma...

1813 Connecticut gubernatorial election 1813 Connecticut gubernatorial election ← 1812 April 12, 1813 1814 → Nominee John Cotton Smith Elijah Boardman Party Federalist Democratic-Republican Popular vote 11,893 7,201 Percentage 59.12% 35.80% County results Smith: 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% Governor before election John Cotton Smith Federalist Elected Governor John Cotton ...

Charity Shield FA 1935TurnamenCharity Shield FA Sheffield Wednesday Arsenal 1 0 Tanggal23 Oktober 1935StadionStadion Highbury, London← 1934 1936 → Charity Shield FA 1935 adalah pertandingan sepak bola antara Sheffield Wednesday dan Arsenal yang diselenggarakan pada 23 Oktober 1935 di Stadion Highbury, London. Pertandingan ini merupakan pertandingan ke-22 dari penyelenggaraan Charity Shield FA. Pertandingan ini dimenangkan oleh Sheffield Wednesday dengan skor 1–0.[1] Pert...

1995 live album by Audio AdrenalineLive BootlegLive album by Audio AdrenalineReleasedOctober 10, 1995RecordedFall 1994VenueVarious locationsGenreChristian rock, rapLength53:59LabelForeFrontProducerAudio AdrenalineAudio Adrenaline chronology Don't Censor Me(1993) Live Bootleg(1995) Bloom(1996) Live Bootleg is the first live album by American Christian rock band Audio Adrenaline, released on ForeFront Records on October 10, 1995. It contains live recordings of songs from the band's self...

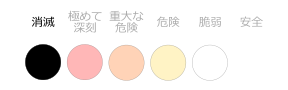

サリナ語話される国 アメリカ合衆国地域 カリフォルニア州消滅時期 1950年代末-1960年代初[1]言語系統 ホカ大語族? サリナ語言語コードISO 639-3 slnGlottolog sali1253[2] 消滅危険度評価 Extinct (Moseley 2010)テンプレートを表示 サリナ語(Salinan language)は、アメリカ合衆国カリフォルニア州のサリナ族によって話されていた言語。現在は死語になっている。 概要 サリナ語は...

Carlo III del Regno UnitoCarlo III nel 2024Re del Regno Unitodi Gran Bretagna e Irlanda del Norde degli altri reami del CommonwealthStemma In caricadall'8 settembre 2022(1 anno e 359 giorni) Incoronazione6 maggio 2023 PredecessoreElisabetta II EredeWilliam, principe del Galles Nome completoinglese: Charles Philip Arthur Georgeitaliano: Carlo Filippo Arturo Giorgio TrattamentoSua Maestà britannica Onorificenzesi veda sezione Altri titoliSignore di ManCapo del Commonwea...

Azərbaycan Kuboku 2012-2013 Competizione Azərbaycan Kuboku Sport Calcio Edizione 21ª Organizzatore AFFA Date dal 22 ottobre 2012al 28 maggio 2013 Luogo Azerbaigian Partecipanti 21 Risultati Vincitore Neftçi Baku(6º titolo) Secondo Xəzər-Lənkəran Statistiche Incontri disputati 20 Gol segnati 40 (2 per incontro) Cronologia della competizione 2011-2012 2013-2014 Manuale La Azərbaycan Kuboku 2012-2013 è stata la 21ª edizione della coppa nazionale azera,...