Slavery and the United States Constitution

|

Read other articles:

AftershineInformasi latar belakangNama lainTengah Malam(sebelum menjadi Aftershine)AsalKabupaten Sleman, Daerah Istimewa YogyakartaGenrePop JawadangdutkoploTahun aktif2019–sekarangAnggota Hasan Aftershine Andika Permana Putra Hedo Anka Pindo Zulian Achmad Yuniarto Agus Nugroho Yuriko Andrianta Aftershine (sebelumnya bernama Tengah Malam) adalah sebuah grup musik bergenre pop Jawa dan koplo asal Indonesia. Grup musik ini berasal dari Kabupaten Sleman, Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta. Anggota Nama...

i {\displaystyle i} terletak di bidang kompleks. Bilangan riil terletak pada sumbu horizontal, dan bilangan imajiner terletak pada sumbu vertikal. Unit imajiner atau bilangan imajiner unit ( i {\displaystyle i} ) adalah solusi untuk persamaan kuadrat x {\displaystyle x} 2 + 1 = 0 {\displaystyle +1=0} . Meskipun tidak ada bilangan riil dengan sifat ini, i {\displaystyle i} dapat digunakan untuk memperluas bilangan riil menjadi bilangan kompleks, bilangan yang menggunakan operasi penambahan da...

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Мамай (значения). Мамай Мамай на монументе «Тысячелетие России» Беклярбек Золотой Орды 1361 — 1380 Преемник Едигей Рождение на рубеже 1320—1330Солхат, Крым Смерть 1380(1380)Кафа Место погребения Шейх-Мамай, Крым Род Кият Отец Алиш (...

Siraman selama upacara mitoni adalah salah satu upacara tradisional yang dilakukan oleh masyarakat Jawa Mitoni yaitu berasal dari kata tujuh (7). Upacara adat ini diadakan waktu calon ibu menikah atau hamil 7 bulan. Kegunaanya untuk keselamatan calon bayi dan ibu-nya atau untuk yang bersifat menolak bala. Di-daerah tertentu, upacara ini juga diberi nama tingkeban.[1] Makna Janin bayi berumur 7 bulan tersebut sudah mempunyai badan yang sempurna. Jadi menurut pengertianya orang Jawa, ke...

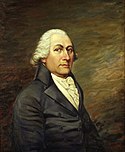

New Hampshire gubernatorial election 1793 New Hampshire gubernatorial election ← 1792 12 March 1793 1794 → Nominee Josiah Bartlett John Langdon John Taylor Gilman Party Anti-Federalist Anti-Federalist Federalist Popular vote 7,388 1,306 708 Percentage 74.98% 13.25% 7.19% Governor before election Josiah Bartlett Anti-Federalist Elected Governor Josiah Bartlett Anti-Federalist Elections in New Hampshire Federal government Presidential elections 1788–89 1792 1...

Harry Potter and the Goblet of FireSutradaraMike NewellProduserDavid Heyman David BarronSkenarioSteve KlovesBerdasarkanNovel:J. K. RowlingPemeranDaniel RadcliffeRupert GrintEmma WatsonRalph FiennesMichael GambonBrendan GleesonRobert PattinsonMiranda RichardsonPenata musikPatrick DoyleTema oleh:John WilliamsSinematograferRoger PrattPenyuntingMick AudsleyDistributorWarner Bros. PicturesTanggal rilis 18 November 2005 (2005-11-18) Durasi157 menitNegaraUKBahasaInggrisAnggaran$150 jutaPe...

Armée de l'air tunisienneالقوات الجوية التونسية Insigne de l'Armée de l'air tunisienne. Création 1959 Pays Tunisie Branche Air Rôle Défense aérienne de la Tunisie Fait partie de Armée tunisienne Garnison Bases Surnom TAF Couleurs Anniversaire 24 juillet Guerres Guerre contre le terrorisme Batailles Bataille de ChaambiBataille de Ben Gardane Commandant Général de brigade Mohamed El Hajjam[1] (chef d'état-major) modifier L'Armée de l'air tunisienne est l'un...

2019 Russian crewed spaceflight to the ISS Soyuz MS-13The Soyuz MS-13 approaches the ISSMission typeCrewed mission to ISSOperatorRoskosmosCOSPAR ID2019-041A SATCAT no.44437Mission duration200d 16h 44mOrbits completed3,216 [1] Spacecraft propertiesSpacecraftSoyuz-MSSpacecraft typeSoyuz-MS 11F747 No. 746ManufacturerRKK Energia CrewCrew size3MembersAleksandr SkvortsovLuca ParmitanoLaunchingAndrew R. MorganLandingChristina KochCallsignCliff Start of missionLaunch date20 July 2019, 16:28:2...

For the American track and field athlete, see Bridget Williams (athlete). Bridget WilliamsONZM MBEWilliams in 2012Born1948 (age 75–76)NationalityNew ZealanderAlma materUniversity of OtagoKnown forfounder of independent publishing companies Port Nicholson Press and Bridget Williams BooksRelativesRobin Williams (father) Bridget Rosamund Williams ONZM MBE (born 1948) is a New Zealand publisher and founder of two independent publishing companies: Port Nicholson Press ...

Questa voce sull'argomento calciatori rumeni è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Alexandru Maxim Nazionalità Romania Altezza 178 cm Calcio Ruolo Centrocampista Squadra Gaziantep Carriera Giovanili 1997-2004 Olimpia Piatra Neamț2004-2007 Ardealul2007-2009 Espanyol Squadre di club1 2009-2010 Espanyol B26 (0)2010-2011→ Badalona5 (0)2011-2013 Pandurii44...

Protestants who denied transubstantiation Reading of the Confessio Augustana by Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Augsburg, 1530 The Sacramentarians were Christians during the Protestant Reformation who denied not only the Roman Catholic transubstantiation but also the Lutheran sacramental union (as well as similar doctrines such as consubstantiation).[1] During the turbulent final years of Henry VIII's reign an influential faction of religious conservatives had dedicated themselves to...

The WorksAlbum kompilasi karya The CorrsDirilis27 Agustus 200725 September 2007GenrePop, Folk-rockLabelRhino RecordsKronologi The Corrs Dreams: The Ultimate Corrs Collection(2006)Dreams: The Ultimate Corrs Collection2006 The Works(2007) Original Album Series (2011)String Module Error: Match not foundString Module Error: Match not found The Works adalah album kompilasi ketiga yang dirilis oleh The Corrs. Album ini terdiri dari tiga CD yang berisikan lagu-lagu pilihan yang dirilis di album...

Melodi dan syair pertama Va, pensiero Va, pensiero adalah lagu paduan suara karya Giuseppe Verdi yang di inspirasi dari Mazmur 137. Lagu ini merupakan lagu ketiga dalam opera Nobucco (1842). Lagu ini dikenal sebagai karya seni Yahudi Verdi, ia mengingat kisah orang-orang buangan Yahudi dari Yudea setelah kehilangan Kuil Pertama di Yerusalem. Opera dengan paduan suara yang megah didirikan Verdi sebagai komposer utama dalam abad ke-19 Italia. Peran dalam sejarah politik Italia Beberapa cendekia...

This article is part of a series on theConstitutionof the United States Preamble and Articles Preamble I II III IV V VI VII Amendments to the Constitution I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII Unratified Amendments: Congressional Apportionment Titles of Nobility Corwin Child Labor Equal Rights D.C. Voting Rights History Drafting and ratification timeline Convention Signing Federalism Republicanism Bill of Rights Reconstruct...

Голубянки Самец голубянки икар Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ПервичноротыеБез ранга:ЛиняющиеБез ранга:PanarthropodaТип:ЧленистоногиеПодтип:ТрахейнодышащиеНадкласс:ШестиногиеКласс...

سير تيم بيرنرز لي (بالإنجليزية: Tim Berners-Lee) معلومات شخصية اسم الولادة (بالإنجليزية: Timothy John Berners-Lee) الميلاد 8 يونيو 1955 (69 سنة)[1][2][3][4] لندن[5] الإقامة كونكورد مواطنة المملكة المتحدة[6] الديانة توحيدية عالمية[7][8] عض...

ملحمة الحب والرحيل النوع تاريخي [لغات أخرى]، ودراما تلفزيونية [لغات أخرى] مبني على حرب البسوس سيناريو وليد سيف البلد مصر عدد الحلقات 18 السينما.كوم 1011010 تعديل مصدري - تعديل ملحمة الحب والرحيل هو مسلسل عربي، بطله تركي ابوحماد ، يح...

Achôris Statue d'Achôris, XXIXe dynastie,Boston, musée des Beaux-Arts. Fonctions Pharaon d'Égypte vers -393 – 380 av. J.-C. Prédécesseur Psammouthis Successeur Néphéritès II Biographie Dynastie XXIXe dynastie Basse époque Date de décès vers -380 Enfants Néphéritès II modifier Partie haute d'une statue d'Achôris par William Matthew Flinders Petrie. Achôris accède au trône d'Égypte vers -393 et règne pendant 14 ans. Règne Cette période est un renou...

NOAA environmental products and services Oceanic and Atmospheric ResearchNational Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration sealAgency overviewFormed1841; 183 years ago (1841)HeadquartersSilver Spring, Maryland, U.S.[1]MottoOAR's Vision is to deliver NOAA’s future. OAR's Mission is to conduct research to understand and predict the Earth’s oceans, weather and climate, to advance NOAA science, service and stewardship and transition the results so they are useful to so...

History of geography Graeco-Roman Chinese Islamic Age of Discovery History of cartography Historical geography Environmental determinism Regional geography Quantitative revolution Critical geography vte This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: History of geography – news · newspapers · books · scholar ...