Russians in Serbia

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

artikel ini tidak memiliki pranala ke artikel lain. Tidak ada alasan yang diberikan. Bantu kami untuk mengembangkannya dengan memberikan pranala ke artikel lain secukupnya. (Pelajari cara dan kapan saatnya untuk menghapus pesan templat ini) Berkas:Hughes Helicopters logo.svg.png Berkas:1 PENERBAD 50 th 004.jpg Hughes Helicopters adalah produsen utama helikopter militer dan sipil dari tahun 1950 hingga 1980-an. Perusahaan mulai tahun 1947, sebagai unit Hughes Aircraft, saat itu adalah bagian d...

Halaman ini berisi artikel tentang buku. Untuk peristiwa sejarah, lihat Sejarah Kekaisaran Romawi dan Keruntuhan Kekaisaran Romawi Barat. Untuk historiografi yang dipegang oleh teori-teori Gibbon, lihat Historiografi keruntuhan Kekaisaran Romawi Barat. Sejarah Kemunduran dan Kejatuhan Kekaisaran Romawi PengarangEdward GibbonNegaraInggrisBahasaInggrisSubjekSejarah Kekaisaran RomawiPenerbitStrahan & Cadell, LondonTanggal terbit1776–89Jenis mediaCetakLCCDG311 Edward Gibbon (1737�...

Aquinas beralih ke halaman ini. Untuk kegunaan lain, lihat Aquinas (disambiguasi). Santo Thomas AquinasLatar sebuah altar di Ascoli Piceno, Italia, karya Carlo Crivelli (abad ke-15)Pujangga GerejaLahir1225Roccasecca, Kerajaan SisiliaMeninggal7 Maret 1274 – 1225; umur -50–-49 tahunFossanova, Negara GerejaDihormati diGereja KatolikKomuni AnglikanLutheranismeKanonisasi18 Juli 1323, Avignon, Negara Gereja oleh Paus Yohanes XXIITempat ziarahGereja Jacobins, Toulouse, PrancisPesta2...

ا بوكاسبور الاسم الكامل بوكاسبورBucaspor Kulübü اللقب فيرتينا (العاصفة) تأسس عام 1928 الملعب بوكا أرينا، أزمير تركيا(السعة: 6,236[1]) البلد تركيا الدوري الدوري التركي الدرجة الأولى الإدارة المدرب سوات كايا (لاعب كرة قدم) الموقع الرسمي http://www.bucaspor.org.tr/ الطقم الأساسي الطقم الا�...

Trolls: Original Motion Picture SoundtrackAlbum lagu tema karya Various artistsDirilis23 September 2016 (2016-09-23)Direkam2015–2016StudioRCADurasi35:05LabelRCAProduser Justin Timberlake Earth, Wind & Fire Oscar Holter Max Martin Ilya The Outfit Nile Rodgers Shellback Timbaland Trolls soundtrack Trolls: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack(2016) Trolls World Tour: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack(2020) Singel dalam album Trolls: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack Can't Stop the...

Questa voce sull'argomento calciatori brasiliani è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Márcio Araújo Nazionalità Brasile Altezza 172 cm Peso 70 kg Calcio Ruolo Centrocampista Squadra svincolato Carriera Giovanili 2001-2002 Mogi Mirim Squadre di club1 2003 Corinthians Alagoano0 (0)2003-2004 Atlético Mineiro1 (0)[1]2005→ Guarani35 (1)2006-2007 Atlé...

† Человек прямоходящий Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:Синапсиды�...

Wakil Wali Kota Padang PanjangLambang Kota Padang PanjangPetahanaJabatan Lowongsejak 9 Oktober 2023KediamanRumah Dinas Wakil Wali Kota Padang PanjangMasa jabatan5 tahun, sesudahnya dapat dipilih kembali sekaliDibentuk2003Pejabat pertamaAdirozalSitus webwww.padangpanjang.go.id Wakil Wali Kota Padang Panjang adalah politisi yang dipilih bersama Wali Kota Padang Panjang untuk membantu tugas Wali kota dalam mengatur dan mengelola Pemerintah Kota Padang Panjang, sebagai bagian dari sistem pen...

Sand Point Apartments and other facilities in Sand Point, just at the edge of Magnuson Park Sand Point is a neighborhood in Seattle, Washington, United States, named after and consisting mostly of the Sand Point peninsula that juts into Lake Washington, which is itself largely given over to Magnuson Park. Its southern boundary can be said to be N.E. 65th Street, beyond which are Windermere and Hawthorne Hills; its northern boundary, N.E. 95th Street, beyond which is Lake City. The western lim...

Roti lapis selai kacang dan jeliSebuah roti lapis selai kacang dan jelly menggunakan roti putihNama lainPeanut butter & jelly sandwich, PB&JSajianMakan siang, kudapanTempat asalAmerika SerikatVariasiSelai kacang dan selai rasa lain, pasta kacang, dengan mentega atau lelehan marshmallowEnergi makanan(per porsi )403 kkal, 18 g lemak, 58 g karbohidrat, 28 g protein[1] kkalSunting kotak info • L • BBantuan penggunaan templat ini Buku resep: Roti lapis selai kaca...

For the academic discipline, see Art history. Venus of Hohle FelsHorse painting from Lascaux cave systemMask of TutankhamunVenus de Milo, Alexandros of AntiochMona Lisa, Leonardo da VinciLes Demoiselles d'Avignon, Pablo Picasso History of art Periods and movements Prehistoric Ancient Medieval Pre-Romanesque Romanesque Gothic Renaissance Mannerism Baroque Rococo Neoclassicism Revivalism Romanticism Realism Pre-Raphaelites Modern Impressionism Symbolism Decorative Post-Impressionism Art Nouvea...

兜造りの古民家(東京都檜原村) 山梨県富士河口湖町、「西湖いやしの里根場」に再現された兜造りの古民家群 前兜造りの古民家(群馬県吾妻郡中之条町、国指定重要文化財 富沢家住宅) 兜造り(かぶとづくり)は、日本の民家における屋根形式の一つである。かつて日本の武士が用いた兜に似ていることから名付けられた。 解説 基本的には寄棟造あるいは入母屋...

2010 United States Shadow Representative election in the District of Columbia ← 2008 November 2, 2010 2012 → Turnout30.0% 32.5 pp[1] Nominee Mike Panetta Nelson Rimensnyder Joyce Robinson-Paul Party Democratic Republican DC Statehood Green Popular vote 101,207 11,094 9,489 Percentage 82.4% 9.0% 7.7% Ward results Precinct resultsPanetta: 50–60% 60–70% 70–80...

Danish engineer Valdemar PoulsenValdemar Poulsen (c. 1898)Born23 November 1869Copenhagen, DenmarkDied23 July 1942(1942-07-23) (aged 72)Gentofte, DenmarkNationalityDanishOccupationEngineerEngineering careerProjectsmagnetic wire recorder, arc converter radio transmitter Valdemar Poulsen (23 November 1869 – 6 August 1942) was a Danish engineer who developed a magnetic wire recorder called the telegraphone in 1898. He also made significant contributions to early radio technology, including...

Observance of recitation in religious Judaism Part of a series onJudaism Movements Orthodox Haredi Hasidic Modern Conservative Conservadox Reform Karaite Reconstructionist Renewal Humanistic Haymanot Philosophy Principles of faith Kabbalah Messiah Ethics Chosenness God Names Musar movement Texts Tanakh Torah Nevi'im Ketuvim Ḥumash Siddur Piyutim Zohar Rabbinic Mishnah Talmud Midrash Tosefta Law Mishneh Torah Tur Shulchan Aruch Mishnah Berurah Aruch HaShulchan Kashrut...

Political corruption scandal in Spain You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (June 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions. Machine translation, like DeepL or Google Translate, is a useful starting point for translations, but translators must revise errors as necessary and confirm that the translation is accurate, rather than simply copy-pasting machine-translated text into the English Wikipedia. Do not translate...

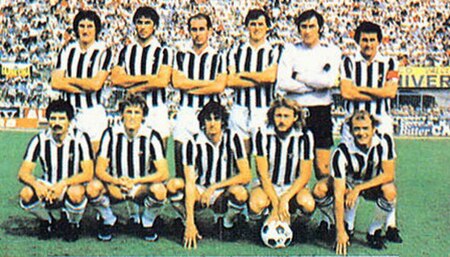

Torneo di Capodanno Sport Calcio Edizione unica Organizzatore LNP — FIGC Date dal 4 gennaio 1981al 14 giugno 1981 Luogo Italia Partecipanti 16 Formula A gironi + play-off Sede finale Stadio Del Duca, Ascoli Piceno Direttore Renzo Righetti Risultati Vincitore Ascoli(unico titolo) Finalista Juventus Statistiche Miglior marcatore 13 giocatori (2) Incontri disputati 19 Gol segnati 45 (2,37 per incontro) Pubblico 83 288 (4 384 per incontro) Una formazione dell'...

LVTP-5 LVTP-5类型兩棲裝甲運兵車原产地 美国服役记录服役期间1952-参与战争/衝突1958年黎巴嫩危機越戰生产历史研发者博格華納研发日期1950-1951制造数量1124基本规格重量37.4公噸长度9.04公尺宽度3.57公尺高度2.92公尺操作人数3+34 乘員装甲6-16公厘的鋼質裝甲主武器M1919A4機槍(A、A1)、白朗寧M2重機槍(A1與其他款式)、M240通用機槍(LVTH-6)、M49 24倍徑105mm榴彈炮(LVTH-6)、工蜂四型(LVTP-...

Geometric graph with unit edge lengths A unit distance graph with 16 vertices and 40 edges In mathematics, particularly geometric graph theory, a unit distance graph is a graph formed from a collection of points in the Euclidean plane by connecting two points whenever the distance between them is exactly one. To distinguish these graphs from a broader definition that allows some non-adjacent pairs of vertices to be at distance one, they may also be called strict unit distance graphs or faithf...

40th Government of Kingdom of Italy Giolitti II government40th Cabinet of ItalyDate formed3 November 1903Date dissolved12 March 1905People and organisationsHead of stateVictor Emmanuel IIIHead of governmentGiovanni GiolittiTotal no. of members11Member partyHistorical LeftHistorical RightHistoryPredecessorZanardelli CabinetSuccessorTittoni Cabinet The Giolitti II government of Italy held office from 3 November 1903 until 12 March 1905, a total of 499 days, or 1 year, 4 months and 13 days.[...