Rufous hornero

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Часть серии статей о Холокосте Идеология и политика Расовая гигиена · Расовый антисемитизм · Нацистская расовая политика · Нюрнбергские расовые законы Шоа Лагеря смерти Белжец · Дахау · Майданек · Малый Тростенец · Маутхаузен ·&...

Pomadasys Pomadasys kaakan Klasifikasi ilmiah Domain: Eukaryota Kerajaan: Animalia Filum: Chordata Kelas: Actinopterygii Ordo: Perciformes Famili: Haemulidae Subfamili: Haemulinae Genus: PomadasysLacépède, 1802 Spesies tipe Pomadasys argenteus(Forsskål, 1775) Spesies Lihat teks Sinonim[1] Anomalodon S. Bowdich, 1825 Dacymba D. S. Jordan & C. L. Hubbs, 1917 Polotus Blyth, 1858 Pomadasyina Fowler, 1931 Pristipoma Quoy & Gaimard, 1824 Pristipomus Oken, 1817 Rhencus D. S. Jord...

Sanitiar Burhanuddin Jaksa Agung Republik Indonesia ke-24PetahanaMulai menjabat 23 Oktober 2019PresidenJoko WidodoWakil PresidenMa'ruf AminWakilSetia Untung ArimuladiSunartaPendahuluMuhammad Prasetyo Arminsyah(Pelaksana Tugas)PenggantiPetahana Informasi pribadiLahir17 Juli 1954 (umur 69)Cirebon, Jawa Barat, IndonesiaKebangsaanIndonesiaOrang tuaEntis Sutisna (ayah)Jojoh Juansih (ibu)KerabatTubagus Hasanuddin (kakak)Alma materGuru Besar Fakultas Hukum Universitas Jenderal Soedirman...

この記事は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。(このテンプレートの使い方)出典検索?: コルク – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii · J-STAGE · NDL · dlib.jp · ジャパンサーチ · TWL(2017年4月) コルクを打ち抜いて作った瓶の栓 コルク(木栓、�...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Grand Palais. Grand palaisΜέγα ΠαλάτιονVestige du Palais de Boucoléon, qui faisait partie du Palais SacréPrésentationType PalaisCivilisation Empire byzantinDestination initiale Résidence des basileusStyle Architecture byzantineÉtat de conservation démoli ou détruit (d)LocalisationPays Empire byzantinCommune ConstantinopleCoordonnées 41° 00′ 23″ N, 28° 58′ 40″ E Géolocalisation sur la carte : T...

هذه المقالة عن المجموعة العرقية الأتراك وليس عن من يحملون جنسية الجمهورية التركية أتراكTürkler (بالتركية) التعداد الكليالتعداد 70~83 مليون نسمةمناطق الوجود المميزةالبلد القائمة ... تركياألمانياسورياالعراقبلغارياالولايات المتحدةفرنساالمملكة المتحدةهولنداالنمساأسترالي�...

Australian rugby league footballer Dean SchifillitiPersonal informationBorn (1968-03-30) 30 March 1968 (age 56)Ingham, Queensland, AustraliaHeight177 cm (5 ft 10 in)Weight90 kg (14 st 2 lb)Playing informationPositionHooker Club Years Team Pld T G FG P 1989–93 Illawarra Steelers 102 16 0 0 64 1994 South Sydney 6 0 0 0 0 1995–96 North Queensland 11 0 0 0 0 1997–98 Adelaide Rams 35 6 0 0 24 1999–00 Parramatta Eels 30 1 0 0 4 Total 184 23 0 0 92 Source: ...

ヨハネス12世 第130代 ローマ教皇 教皇就任 955年12月16日教皇離任 964年5月14日先代 アガペトゥス2世次代 レオ8世個人情報出生 937年スポレート公国(中部イタリア)スポレート死去 964年5月14日 教皇領、ローマ原国籍 スポレート公国親 父アルベリーコ2世(スポレート公)、母アルダその他のヨハネステンプレートを表示 ヨハネス12世(Ioannes XII、937年 - 964年5月14日)は、ロ...

Official workplace of the president of Kazakhstan You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (August 2012) Click [show] for important translation instructions. Machine translation, like DeepL or Google Translate, is a useful starting point for translations, but translators must revise errors as necessary and confirm that the translation is accurate, rather than simply copy-pasting machine-translated text into the English Wikipedia. Do...

Irish language radio station RTÉ Raidió na GaeltachtaBroadcast areaIreland: FM, DAB, TVNorthern Ireland: FM, TVUnited Kingdom: Satellite radioWorldwide: Internet radioFrequencyFM: 92 MHz - 94 MHz (Ireland)102.7 MHz (Northern Ireland) Digital terrestrial televisionRDSRTE RnaGProgrammingFormatIrish-language speech and musicOwnershipOwnerRaidió Teilifís ÉireannSister stationsRTÉ Radio 1RTÉ 2fmRTÉ lyric fmRTÉ PulseRTÉ 2XMRTÉ Jr RadioRTÉ ChillRTÉ GoldRTÉ Radio 1 ExtraHistoryFirst air...

LamanaiThe High Temple of LamanaiLocation within MesoamericaLocationOrange Walk District, BelizeRegionOrange Walk DistrictCoordinates17°45′9″N 88°39′16″W / 17.75250°N 88.65444°W / 17.75250; -88.65444HistoryFounded16th century BCPeriodsPreclassic to PostclassicCulturesMaya civilization Lamanai (from Lama'anayin, submerged crocodile in Yucatec Maya) is a Mesoamerican archaeological site, and was once a major city of the Maya civilization, located i...

Voce principale: Società Sportiva Dilettantistica Pro Sesto. Associazione Calcio Pro SestoStagione 1993-1994Sport calcio Squadra Pro Sesto Allenatore Gianfranco Motta Presidente Giuseppe Peduzzi Serie C16º posto Coppa Italia2ª nel girone D Maggiori presenzeCampionato: Fabio Macellari (33) Miglior marcatoreCampionato: Nunzio Falco (6) StadioStadio Breda 1992-1993 1994-1995 Si invita a seguire il modello di voce Questa pagina raccoglie le informazioni riguardanti l'Associazione Calcio ...

Skyscraper in North Carolina, United States 200 South CollegeFormer namesBB&T CenterGeneral informationStatusCompletedTypeOfficeArchitectural styleModernLocation200 South College Street, Charlotte, North CarolinaCoordinates35°13′31″N 80°50′37″W / 35.22528°N 80.84361°W / 35.22528; -80.84361Opening1975; 49 years ago (1975)OwnerBB&T Properties LLC[1]HeightRoof300 ft (91 m)Technical detailsFloor count22Floor area567,8...

この記事は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。 出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。(このテンプレートの使い方)出典検索?: 時刻 – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii · J-STAGE · NDL · dlib.jp · ジャパンサーチ · TWL (2018年3月) 現代のデジタル時計の時刻表示 古代エジプトの日時計...

اضغط هنا للاطلاع على كيفية قراءة التصنيف ثنائيات التناظرالعصر: العصر الإدياكاري – الآن قك ك أ س د ف بر ث ج ط ب ن المرتبة التصنيفية عويلم[1] التصنيف العلمي النطاق: حقيقيات النوى المملكة: حشرات العويلم: بعديات حقيقية غير مصنف: ثنائيات التناظرHatschek، 1888 الاسم العلمي Bilateria&...

Парижский парламентParlement parisien Юрисдикция Королевство Франция (Париж) Дата основания 1260 год Языки делопроизводства французский Зал заседаний Большая палата парламента на острове Сите — там, где сейчас высится Дворец Правосудия Местоположение Париж Lit de justice 12 сентября 17...

هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالات أخرى قليلة جدًا. فضلًا، ساعد بإضافة وصلة إليها في مقالات متعلقة بها. (أبريل 2019) برونو إتيان (بالفرنسية: Bruno Étienne) معلومات شخصية اسم الولادة (بالفرنسية: Bruno Pierre Lucien Étienne) الميلاد 6 نوفمبر 1937 [1][2] لا ترونش الوفاة 4 م...

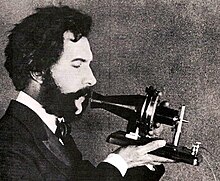

Actor portraying Alexander Graham Bell in a 1932 silent film. Shows Bell's second telephone transmitter (microphone), invented 1876 and first displayed at the Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia. This history of the telephone chronicles the development of the electrical telephone, and includes a brief overview of its predecessors. The first telephone patent was granted to Alexander Graham Bell in 1869. Mechanical acoustic devices A 19th century acoustic tin can or lovers' telephone Before th...

Prima Divisione 1941-1942 Competizione Prima Divisione Sport Calcio Edizione 21ª Organizzatore FIGC e Direttori di Zona Luogo Italia Cronologia della competizione 1940-1941 1942-1943 Manuale Fu il quarto livello della XLII edizione del campionato italiano di calcio. La Prima Divisione fu organizzata e gestita dai Direttori di Zona.[1] Le finali per la promozione in Serie C erano gestiti dal Direttorio Divisioni Superiori (D.D.S.) che aveva sede a Roma. Rispetto all'anno preced...

Seranscomune Serans – Veduta LocalizzazioneStato Francia RegioneAlta Francia Dipartimento Oise ArrondissementBeauvais CantoneChaumont-en-Vexin TerritorioCoordinate49°11′N 1°50′E49°11′N, 1°50′E (Serans) Altitudine95 e 212 m s.l.m. Superficie8,68 km² Abitanti233[1] (2009) Densità26,84 ab./km² Altre informazioniCod. postale60240 Fuso orarioUTC+1 Codice INSEE60614 CartografiaSerans Sito istituzionaleModifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Seran...