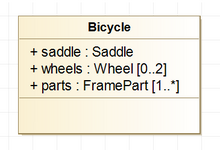

Object composition

|

Read other articles:

KaryamuktiDesa Pemandangan Desa KaryamuktiNegara IndonesiaProvinsiJawa BaratKabupatenMajalengkaKecamatanPanyingkiranKode pos45459Kode Kemendagri32.10.18.2009 Luas3.05 km²Jumlah penduduk5592 jiwaKepadatan1520,84 jiwa/km²Jumlah RT29 RTJumlah RW6 RWSitus webkaryamukti.com Karyamukti adalah desa di kecamatan Panyingkiran, Majalengka, Jawa Barat, Indonesia. Desa ini terbagi menjadi 2 Dusun yang dibatasi oleh Jl. Raya Siliwangi Km. 7. Desa Karyamukti merupakan Desa yang mempunyai arti tersen...

Часть серии статей о Холокосте Идеология и политика Расовая гигиена · Расовый антисемитизм · Нацистская расовая политика · Нюрнбергские расовые законы Шоа Лагеря смерти Белжец · Дахау · Майданек · Малый Тростенец · Маутхаузен ·&...

Sungai LekopancingEtimologiLekopancing dalam Bahasa Makassar, terdiri dari dua kata yaitu Leko artinya daun sirih dan Pancing artinya bersih. Jadi, Lekopancing berarti daun sirih yang bersih.LokasiNegara IndonesiaProvinsiSulawesi SelatanKabupatenMarosInformasi lokalZona waktuWITA (UTC+8) Sungai Lekopancing (Bahasa Inggris: Lekopancing River) adalah sebuah sungai yang terletak di wilayah Kabupaten Maros, Provinsi Sulawesi Selatan, Indonesia. Sungai Lekopancing telah dijadikan sebagai sumb...

Ne Winနေဝင်းNe Win pada tahun 1959 Ketua Partai Program Sosialis BurmaMasa jabatan4 Juli 1962 – 23 Juli 1988 PendahuluPartai didirikanPenggantiSein LwinPresiden Myanmar ke-4Masa jabatan2 Maret 1962 – 9 November 1981(Ketua Persatuan Dewan Revolusioner sampai 2 Maret 1974) PendahuluWin Maung (1962)PenggantiSan YuPerdana Menteri Myanmar ke-3Masa jabatan29 Oktober 1958 – 4 April 1960 PendahuluU NuPenggantiU NuMasa jabatan2 Maret 1962 – 2 Mar...

كأس بلغاريا 2015–16 تفاصيل الموسم كأس بلغاريا النسخة 94 البلد بلغاريا التاريخ بداية:23 سبتمبر 2015 نهاية:24 مايو 2016 المنظم اتحاد بلغاريا لكرة القدم البطل سسكا صوفيا مباريات ملعوبة 33 عدد المشاركين 32 كأس بلغاريا 2014–15 كأس بلغاريا 2016–17 تعديل مصد...

† Человек прямоходящий Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:Синапсиды�...

Artikel ini memiliki beberapa masalah. Tolong bantu memperbaikinya atau diskusikan masalah-masalah ini di halaman pembicaraannya. (Pelajari bagaimana dan kapan saat yang tepat untuk menghapus templat pesan ini) Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: Mitsubishi F-2 – ...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento baseball non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Stati Uniti Sport Baseball Federazione USA Baseball Confederazione COPABE World Baseball Classic Partecipazioni 4 (esordio: 2006) Miglior risultato 1º Giochi olimpici Partecipazioni 5 (esordio: 1992) Miglior risultato 1° Mondiali Partecipazioni 23 (esordio: 19...

Largest known fish species See also: List of longest fish Life restoration of the extinct Leedsichthys, one of the largest bony fish to have ever lived Fish vary greatly in size. The whale shark and basking shark exceed all other fish by a considerable margin in weight and length. Fish are a paraphyletic group that describes aquatic vertebrates while excluding tetrapods, and the bony fish that often represent the group are more closely related to cetaceans such as whales, than to the cartilag...

No debe confundirse con Nutria marina. Nutria gigante Estado de conservaciónEn peligro (UICN 3.1)[1]TaxonomíaReino: AnimaliaFilo: ChordataSubfilo: VertebrataClase: MammaliaOrden: CarnivoraSuborden: CaniformiaFamilia: MustelidaeSubfamilia: LutrinaeDistribución Distribución de P. brasiliensis[editar datos en Wikidata] La nutria gigante, lobo gargantilla, arirai o ariray (Pteronura brasiliensis) es una especie de mamífero carnívoro que pertenece a la subfamilia...

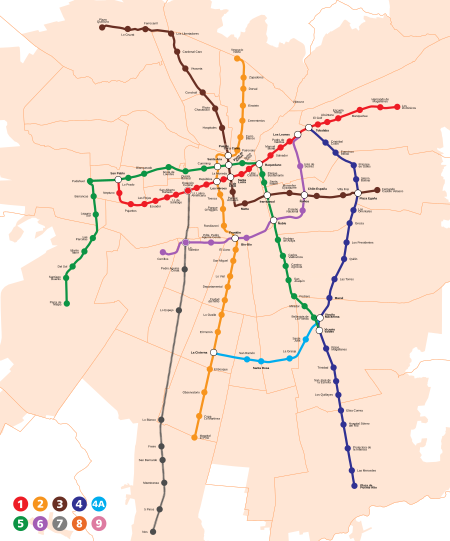

Rapid transit system in Santiago, Chile Santiago MetroNS 93 train on an elevated portion of the line 5.AS-2014 train on the line 6 side of Los Leones.OverviewNative nameMetro de SantiagoLocaleSantiago, ChileTransit typeRapid transitNumber of lines7[1]Number of stations143[1]Daily ridership2.35 million (avg. weekday, 2017)[2]Annual ridership685 million (2017)[2]WebsiteMetro de SantiagoOperationBegan operation15 September 1975[3]Operator(s)es:Metro S.A.Te...

本表是動態列表,或許永遠不會完結。歡迎您參考可靠來源來查漏補缺。 潛伏於中華民國國軍中的中共間諜列表收錄根據公開資料來源,曾潛伏於中華民國國軍、被中國共產黨聲稱或承認,或者遭中華民國政府調查審判,為中華人民共和國和中國人民解放軍進行間諜行為的人物。以下列表以現今可查知時間為準,正確的間諜活動或洩漏機密時間可能早於或晚於以下所歸�...

المشير عبد ربه منصور هادي الرئيس الثاني للجمهورية اليمنية في المنصب25 فبراير 2012 – 7 أبريل 2022 رئيس الوزراء علي محمد مجور محمد سالم باسندوة خالد محفوظ بحاح أحمد عبيد بن دغر معين عبد الملك سعيد نائب الرئيس خالد محفوظ بحاح علي محسن الأحمر علي عبد الله صالح رشاد محمد العليم...

English Victoria Cross recipient (1893–1982) Cyril Edward GourleyBorn19 January 1893Liverpool, EnglandDied31 January 1982 (aged 89)Haslemere, Surrey, EnglandBuriedGrange Cemetery, West Kirby, Wirral, EnglandAllegiance United KingdomService/branch British ArmyYears of service1914–1919RankCaptainUnitRoyal Field ArtilleryBattles/warsWorld War IAwardsVictoria CrossMilitary MedalCroix de guerre (France)[1] Captain Cyril Edward Gourley VC MM (19 January 1893 – 31 Januar...

For related races, see 1964 United States gubernatorial elections. 1964 Washington gubernatorial election ← 1960 November 3, 1964 1968 → Nominee Daniel J. Evans Albert Rosellini Party Republican Democratic Popular vote 697,256 548,692 Percentage 55.8% 43.9% County resultsEvans: 50–60% 60–70% 70–80%Rosellini: 50–60% Governor before e...

Commune and city in Atlantique Department, BeninAlladaCommune and cityAlladaLocation in BeninCoordinates: 6°39′N 2°09′E / 6.650°N 2.150°E / 6.650; 2.150Country BeninDepartmentAtlantique DepartmentArea • Total381 km2 (147 sq mi)Population (2013) • Total127,512Websitehttp://www.web-africa.org/allada/ Allada is a town, arrondissement, and commune, located in the Atlantique Department of Benin. The current town of Al...

Scottish actor and comedian (born 1942) For the Netflix character Billie Connelly, see Sex/Life. SirBilly ConnollyCBEConnolly at the premiere of Brave in 2012Birth nameWilliam ConnollyBorn (1942-11-24) 24 November 1942 (age 81)Anderston, Glasgow, ScotlandMediumFilmstand-uptelevisionYears active1965–presentGenresScottish comedyblue comedymusical comedyobservational comedySpouse Iris Pressagh (m. 1969; div. 1985) Pamela Stephenson&...

Nándor Hidegkuti Nándor Hidegkuti en 1965. Biographie Nationalité Hongrois Naissance 3 mars 1922 Budapest (Hongrie) Décès 14 février 2002 (à 79 ans) Budapest (Hongrie) Taille 1,76 m (5′ 9″) Période pro. 1940 – 1958 Poste Attaquant puis entraîneur Parcours professionnel1 AnnéesClub 0M.0(B.) 1940-1943 Gázmüvek 1943-1945 Elektromos 053 0(27) 1945-1947 Herminamezei AC 1947-1958 MTK 314 (226) Sélections en équipe nationale2 AnnéesÉquipe 0M.0(B.) 1945-1958 Hong...

American teen drama television series The Secret Life of the American TeenagerAlso known asSecret LifeGenreTeen dramaCreated byBrenda HamptonStarring Shailene Woodley Kenny Baumann Mark Derwin India Eisley Greg Finley Daren Kagasoff Jorge-Luis Pallo Megan Park Francia Raisa Molly Ringwald Steve Schirripa Theme music composerDan FoliartOpening themeLet's Do It, Let's Fall In Love, performed by Molly RingwaldComposerDan FoliartCountry of originUnited StatesOriginal languageEnglishNo. of seasons...

此條目需要編修,以確保文法、用詞、语气、格式、標點等使用恰当。 (2017年1月4日)請按照校對指引,幫助编辑這個條目。(幫助、討論) 巴赫里马木留克的最大疆界,蓝色表示伊尔汗国。 巴赫里王朝,又名拜赫里耶的马木留克(al-Mamalik al-Bahariyya المماليك البحرية),由钦察突厥人建立的马木留克政权,自1250年至1382年统治埃及,后被另一个马木留克政权布尔吉王朝...