John Isaac Thornycroft

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Hanyalah CintaAlbum studio karya ElementDirilis25 Desember 1999GenrePopDurasi44:25LabelUniversal Music IndonesiaGP RecordsKronologi Element Hanyalah Cinta (1999) Kupersembahkan Nirwana (2001)Kupersembahkan Nirwana2001 Hanyalah Cinta adalah album musik pertama dari grup band Element yang dirilis pada tahun 1999. Berisi 10 buah lagu dengan Hanyalah Cinta dan Galau sebagai lagu utama dari album ini. Album ini merupakan satu-satunya album Element bersama Ronny Setiawan sebagai vokalis sebelum...

Katedral Salib Suci adalah sebuah situs sejarah dari kompleks keagamaan Gereja Apostolik Armenia yang terletak di Pulau Aghtamar, Danau Van, Turki. Katedral tersebut dibangun antara tahun 915-921 oleh arsitek Manuel, mengikuti perintah Raja Armenia Gagik I Ardzruni, yang merupakan penguasa Kerajaan Vaspurakan. Katedral tersebut dibuka untuk peribadatan satu tahun sekali dengan izin khusus Kementerian Kebudayaan dan Pariwisata Turki. Katedral tersebut masuk ke Daftar Warisan Dunia Sementara U...

This article is about the Bollywood film. For the 2006 American film, see The Holiday. 2006 Indian filmHolidayTheatrical posterDirected byPooja BhattProduced byPooja BhattStarringDino MoreaOnjolee NairKashmera ShahMusic byRanjit BarotRelease date10 February 2006 (2006-02-10)CountryIndiaLanguageHindi Holiday is a 2006 Indian romantic dance film produced and directed by Pooja Bhatt and starring Dino Morea, Gulshan Grover and Onjolee Nair. It is a remake of the 1987 American film ...

See also: 2020 United States Senate elections Not to be confused with 2020 Georgia State Senate election. For the other Senate election in Georgia held in parallel, see 2020–21 United States Senate special election in Georgia. 2020–21 United States Senate election in Georgia ← 2014 November 3, 2020 (first round)January 5, 2021 (runoff) 2026 → Turnout65.4% (first round)61.5% (runoff) Candidate Jon Ossoff David Perdue Party Democratic Republican First round 2,37...

Синелобый амазон Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:ЗавропсидыКласс:Пт�...

Club GuaraníCalcio Aurinegros, El Aborigen, El Cacique Segni distintivi Uniformi di gara Casa Trasferta Colori sociali Giallo, nero Simboli Indiano d'america Dati societari Città Asunción Nazione Paraguay Confederazione CONMEBOL Federazione APF Campionato División Profesional Fondazione 1903 Presidente Federico Acosta Allenatore Fernando Jubero Stadio stadio Rogelio Livieres(8 000 posti) Sito web www.clubguarani.com.py Palmarès Titoli nazionali 11 Campionati paraguaiani Trofei naz...

Voce principale: Ternana Calcio. Ternana CalcioStagione 1976-1977 Sport calcio Squadra Ternana Allenatore Edmondo Fabbri (1ª-11ª) Cesare Maldini (12ª-24ª) Omero Andreani (25ª-38ª) Presidente Gianfranco Tiberi Serie B14º posto Coppa ItaliaPrimo turno Maggiori presenzeCampionato: Zanolla (34) Miglior marcatoreCampionato: Pezzato (7) StadioLibero Liberati 1975-1976 1977-1978 Si invita a seguire il modello di voce Questa voce raccoglie le informazioni riguardanti la Ternana Calcio ne...

Deputy Chief Minister of Rajasthan of Rajasthanराजस्थान के उप-मुख्यमंत्रीEmblem of the State of RajasthanIncumbentDiya KumariandPrem Chand Bairwasince 15 December 2023Government of RajasthanMember of Rajasthan Legislative Assembly Rajasthan Cabinet Reports toThe Chief MinisterNominatorChief Minister of RajasthanAppointerGovernor of RajasthanInaugural holderTika Ram PaliwalWebsiteRajasthan.gov.in The Deputy Chief Minister of Rajasthan is a pa...

Large language model developed by Google This article is about the language model. For the chatbot, see Gemini (chatbot). GeminiDeveloper(s)Google DeepMindInitial releaseDecember 6, 2023; 4 months ago (2023-12-06)PredecessorPaLM 2Available inEnglishTypeLarge language modelLicenseProprietaryWebsitedeepmind.google/technologies/gemini/#introduction Gemini is a family of multimodal large language models developed by Google DeepMind, serving as the successor to LaMDA and Pa...

This article is about the national park. For the peninsula, see Mornington Peninsula. Protected area in Victoria, AustraliaMornington Peninsula National ParkVictoriaIUCN category II (national park) Elephant Rock, one of the park's landmarks.Mornington Peninsula National ParkNearest town or cityMelbourneCoordinates38°30′08″S 144°53′18″E / 38.50222°S 144.88833°E / -38.50222; 144.88833Established 1 December 1975 (1975-12-01)(as Cape Schanck Coas...

فرانك سيناترا (بالإنجليزية: Frank Sinatra) فرانك سيناترا في شبابه معلومات شخصية اسم الولادة (بالإنجليزية: Francis Albert Sinatra) الميلاد 12 ديسمبر 1915(1915-12-12)هوبوكين، نيو جرسي، الولايات المتحدة الوفاة 14 مايو 1998 (82 سنة)لوس أنجلوس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة سبب الوفاة نوبة قلبية&#...

Disambiguazione – Se stai cercando uno degli omonimi papi di Alessandria, vedi Giovanni VI di Alessandria. Papa Giovanni VI85º papa della Chiesa cattolicaElezione30 ottobre 701 Fine pontificato11 gennaio 705(3 anni e 73 giorni) Cardinali creativedi categoria Predecessorepapa Sergio I Successorepapa Giovanni VII NascitaEfeso, 655 MorteRoma, 11 gennaio 705 SepolturaAntica basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano Manuale Giovanni VI (Efeso, 655 – Roma, 11 gennaio 705) è stato l'...

Rasmus Kristensen Nazionalità Danimarca Altezza 186 cm Peso 70 kg Calcio Ruolo Difensore Squadra Roma CarrieraGiovanili 2003-2010 Brande IF2010-2012 Herning Fremad2012-2016 MidtjyllandSquadre di club1 2016-2018 Midtjylland54 (5)[1]2018-2019 Ajax20 (0)2019-2022 Salisburgo72 (10)2022-2023 Leeds Utd26 (3)2023-→ Roma26 (1)Nazionale 2015 Danimarca U-185 (1)2015-2016 Danimarca U-1913 (2)2016 Danimarca U-201 (0)2016-2019 Danimarca U-2127 (6...

Two raised to an integer power Power of 2 redirects here. For other uses of this and of Power of two, see Power of two (disambiguation) Visualization of powers of two from 1 to 1024 (20 to 210) as base-2 Dienes blocks A power of two is a number of the form 2n where n is an integer, that is, the result of exponentiation with number two as the base and integer n as the exponent. Powers of two with non-negative exponents are integers: 20 = 1, 21 = 2, and 2n is two multiplied by itself n tim...

French writer and lexicographer Louis Gustave Vapereau Louis Gustave Vapereau (4 April 1819 – 18 April 1906) was a French writer and lexicographer famous primarily for his dictionaries, the Dictionnaire universel des contemporains and the Dictionnaire universel des littérateurs. Biography Born in Orléans, Louis Gustave Vapereau studied philosophy at the École Normale Supérieure from 1838 to 1843, writing his thesis on Pascal's Pensées under the supervision of Victor Cousin. He taught p...

2012 Stanley Cup playoffsTournament detailsDatesApril 11–June 11, 2012Teams16Defending championsBoston BruinsFinal positionsChampionsLos Angeles KingsRunner-upNew Jersey DevilsTournament statisticsScoring leader(s)Dustin Brown (Kings)Anze Kopitar (Kings) (20 points)MVPJonathan Quick (Kings)← 20112013 → The 2012 Stanley Cup playoffs was the playoff tournament of the National Hockey League (NHL) for the 2011–12 season. It began on April 11, 2012, after the conclusion ...

Borough in England Cheshire West redirects here. For the former European Parliament constituency, see Cheshire West (European Parliament constituency). Unitary authority area and borough in EnglandCheshire West and ChesterUnitary authority area and boroughChester, the county town of Cheshire and the largest settlement in Cheshire West and ChesterCheshire West and Chester shown within CheshireCoordinates: 53°12′47″N 2°54′07″W / 53.213°N 2.902°W / 53.213; -2....

Norwegian sports club Solberg SKSolberg SK club logoFull nameSolberg SportsklubbSportassociation football, bandy, handboll, track and field athletics, earlier also skiingFounded26 November 1929 (1929-11-26)Based inSolbergelva, Norway Solberg Sportsklubb is a Norwegian sports club from Solbergelva which was founded in 1929. The club has sections for football, bandy, handball and gymnastics. Its local rivals are Mjøndalen and Birkebeineren. Bandy section Solberg play in the Norw...

1422 siege of Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire For other sieges of the city, see List of sieges of Constantinople. Siege of ConstantinoplePart of the Rise of the Ottoman Empire and Byzantine-Ottoman wars.Constantinople in 1422; the oldest surviving map of the cityDate10 June – September 1422LocationConstantinople(modern-day Istanbul, Turkey)Result Byzantine victoryBelligerents Byzantine Empire Ottoman EmpireCommanders and leaders John VIII Palaiologos Manuel II Palaiologos Murad II Miha...

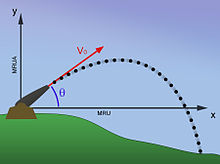

Angle in ballistics This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (April 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) In ballistics, the elevation is the angle between the horizontal plane and the axial direction of the barrel of a gun, mortar or heavy artillery. Originally, elevation was a linear measure of how high t...