Italy–Tunisia relations

| |||||||||

Read other articles:

Akbar Zulfakar Sipanawa Anggota DPR 2009–2014dari Sulawesi TengahPetahanaMulai menjabat 1 Oktober 2009 Informasi pribadiLahir30 Mei 1975 (umur 48)Palu, Sulawesi Tengah, IndonesiaPartai politikPKSSuami/istriSanti NurjanahAnak6Sunting kotak info • L • B Akbar Zulfakar Sipanawa, S.T. (lahir 30 Mei 1975) adalah seorang politikus Indonesia. Ia pernah menjabat sebagai anggota DPR RI periode 2009-2014 fraksi Partai Partai Keadilan Sejahtera. Politisi dari Palu ini terpilih s...

Pulau Sin Cowe Pulau dipersengketakanNama lain: Pulau Sinh TonĐảo Sinh Tồn (Vietnam)Rurok Island (Inggris Filipina)Pulo ng Rurok (Filipina)景宏島 / 景宏岛 Jǐnghóng Dǎo (Tionghoa) Geografi Lokasi Laut Tiongkok Selatan Koordinat 09°53′07″N 114°19′47″E / 9.88528°N 114.32972°E / 9.88528; 114.32972Koordinat: 09°53′07″N 114°19′47″E / 9.88528°N 114.32972°E / 9.88528; 114.32972 Kepulauan Kepulauan Spratly Wilayah a...

Hansal MehtaLahirMumbai, Maharashtra, IndiaPekerjaanSutradara, produser, penulis, dan pemeranTahun aktif1993–sekarang Hansal Mehta adalah seorang sutradara, penulis, pemeran dan produser India. Mehta memulai kariernya di televisi dengan acaranya Khana Khazana (1993–2000) dan kemudian beralih ke film-film seperti …Jayate (1999) dan Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar (2000). Ia paling dikenal karena film Shahid yang membuatnya memenangkan Penghargaan Film Nasional untuk Penyutradaraan Terbaik 2013....

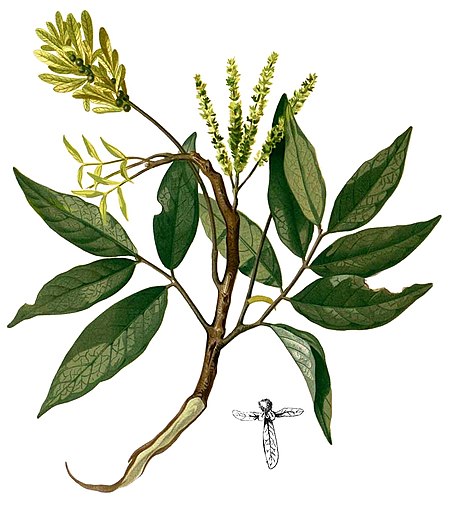

Sowo Engelhardia Engelhardia spicataTaksonomiDivisiTracheophytaSubdivisiSpermatophytesKladAngiospermaeKladmesangiospermsKladeudicotsKladcore eudicotsKladSuperrosidaeKladrosidsKladfabidsOrdoFagalesFamiliJuglandaceaeGenusEngelhardia Blume, 1826 Tipe taksonomiEngelhardia spicata Tata namaStatus nomenklaturnomen conservandum Sinonim takson Alfaropsis Iljinsk. Pterilema Reinw. [1]Ex taxon author (en)Lesch. lbs Engelhardia atau pohon sowo adalah genus pohon dalam keluarga Juglandaceae, bera...

Keuskupan TrevisoDioecesis TarvisinaKatolik Katedral TrevisoLokasiNegaraItaliaProvinsi gerejawiVenesiaStatistikLuas2.194 km2 (847 sq mi)Populasi- Total- Katolik(per 2010)885.220807,020 (91.2%)Paroki265InformasiDenominasiGereja KatolikRitusRitus RomaPendirianAbad ke-4KatedralCattedrale di S. Pietro ApostoloKepemimpinan kiniPausFransiskusUskupMichele TomasiEmeritusGianfranco Agostino Gardin, O.F.M. Conv.Paolo MagnaniPetaSitus webwww.diocesitv.it Keuskupan Trev...

Battle in the Crusade of Varna This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Battle of Varna – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Battle of VarnaPart of the Crusade of Varna and the Ottoman wars in EuropeThe Crusaders were trapped below. Thei...

Disambiguazione – Lucio Silla rimanda qui. Se stai cercando altri significati, vedi Lucio Silla (disambigua). Disambiguazione – Silla rimanda qui. Se stai cercando altri significati, vedi Silla (disambigua). Disambiguazione – Se stai cercando l'opera di Händel, vedi Lucio Cornelio Silla (Händel). Lucio Cornelio SillaConsole e dittatore della Repubblica romanaRitratto di Silla su un denario battuto da suo nipote Quinto Pompeo Rufo Nome originaleLucius Cornelius Su...

SayuriSayuri tampil di Shibuya, Tokyo, Februari 2016.Nama asalさユりLahir7 Juni 1996 (umur 27)Fukuoka, Fukuoka Prefecture, JapanNama lainSanketsu Shōjo Sayuri (酸欠少女さユりcode: ja is deprecated )Pekerjaan Pemusik penyanyi penulis lagur Tahun aktif2010–sekarangTinggi149 cm (4 ft 11 in) 4/11Karier musikGenre J-pop pop Instrumen Vocals guitar LabelAriola Japan[1]Situs webwww.sayuri-official.com Sayuri (さユり, lahir 7 Juni 1996) adal...

US educational nonprofit testing organization College BoardOne of College Board's office buildings in Reston, VAFoundedDecember 22, 1899; 124 years ago (1899-12-22) (as College Entrance Examination Board)TypeNonprofit educationalLocation250 Vesey Street, New York City, New York, U.S. (headquarters)CEODavid ColemanPresidentJeremy SingerRevenue (2019) US$1.11 billion[1]Expenses (2019) US$1.05 billionWebsitecollegeboard.orgFormerly calledCollege Entrance Examination Bo...

Le ministère des Affaires étrangères de la République de Serbie Kneza Miloša (en serbe cyrillique : Кнеза Милоша) est une rue de Belgrade, la capitale de la Serbie. Elle est située dans la municipalité de Savski venac. La rue est ainsi nommée en hommage au prince (en serbe : knez) Miloš Obrenović (1780-1860), qui fut le chef du Second soulèvement serbe contre les Turcs (1815). Localisation La rue Kneza Miloša commence au carrefour de la Place Nikola Pašić, d...

非常尊敬的讓·克雷蒂安Jean ChrétienPC OM CC KC 加拿大第20任總理任期1993年11月4日—2003年12月12日君主伊利沙伯二世总督Ray HnatyshynRoméo LeBlancAdrienne Clarkson副职Sheila Copps赫布·格雷John Manley前任金·坎貝爾继任保羅·馬田加拿大自由黨黨魁任期1990年6月23日—2003年11月14日前任約翰·特納继任保羅·馬田 高級政治職位 加拿大官方反對黨領袖任期1990年12月21日—1993年11月...

هذه المقالة تحتاج للمزيد من الوصلات للمقالات الأخرى للمساعدة في ترابط مقالات الموسوعة. فضلًا ساعد في تحسين هذه المقالة بإضافة وصلات إلى المقالات المتعلقة بها الموجودة في النص الحالي. (أبريل 2015) الاتحاد الدولي للهوكي أعضاء البلدان لمنظمة الاتحاد الدولي لهوكي الرياضة الممث...

Este artículo o sección necesita referencias que aparezcan en una publicación acreditada. Busca fuentes: «IPhone 3G» – noticias · libros · académico · imágenesEste aviso fue puesto el 12 de abril de 2023. iPhone 3G InformaciónTipo Teléfono inteligenteDesarrollador AppleFabricante ApplePantalla LCD TN capacitiva 3,5, 480x320 píxeles, 163 pppInterfaz de entrada Pantalla Táctil y botón únicoRAM 128 MBProcesador Samsung ARM1176JZF-S (412 MHz)Fecha de lanzamie...

American college sports cable network Television channel ESPNUCountryUnited StatesBroadcast areaNationwideInternationalHeadquartersBristol, ConnecticutProgrammingLanguage(s)EnglishPicture format720p (HDTV)Downgraded to letterboxed 480i for SDTV feedOwnershipOwnerThe Walt Disney Company (80%)Hearst Communications (20%)ParentESPN Inc.Sister channelsABCBabyTVDisney ChannelDisney JuniorDisney XDESPNESPN2ESPNewsFreeformFXFXXFX Movie ChannelFYIHistoryHistory en EspanolLifetimeLMNLonghorn NetworkMil...

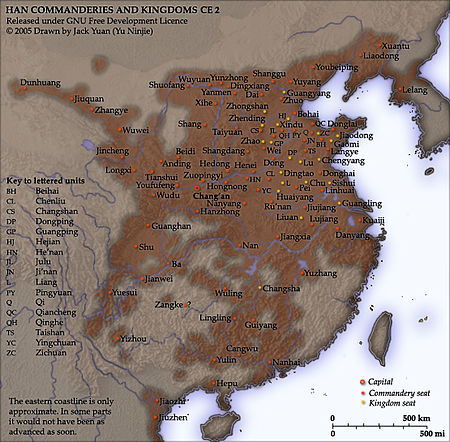

Han Timur beralih ke halaman ini. Untuk kerajaan zaman Lima Dinasti, lihat Han Utara. Koordinat: 34°09′21″N 108°56′47″E / 34.15583°N 108.94639°E / 34.15583; 108.94639 Dinasti Han漢朝202 SM—9 M;25—220 MSebuah peta Dinasti Han Barat pada tahun 2 M: 1) wilayah yang berwarna biru tua mencakup kerajaan semiotonom dan jun yang diperintah langsung dari pusat kekaisaran; 2) wilayah dengan warna biru muda menunjukkan luasnya Protektorat Kawasan Barat di Cekung...

Neptune State Scenic ViewpointCumming Creek enters the ocean at NeptuneShow map of OregonShow map of the United StatesTypePublic, stateLocationLane County, OregonNearest cityWaldportCoordinates44°15′40″N 124°06′29″W / 44.2612317°N 124.108175°W / 44.2612317; -124.108175[1]Operated byOregon Parks and Recreation Department Neptune State Scenic Viewpoint is a state park in the U.S. state of Oregon, administered by the Oregon Parks and Recreat...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Sciences de la nature (homonymie). Sciences de la natureUne chercheuse en sciences de la nature à l'EMPA suisse de Saint-Gall, en 1964.Partie de SciencePratiqué par Naturaliste, étudiant en sciences (d)Champs Science de l'environnementchimiesciences de la Terrephysiquebiologiebiochimiescience spatiale (en)sciences de la vieObjet Naturemodifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata Les sciences de la nature, ou sciences naturelles, ont pour objet le monde...

Geographical distribution of the Italian language in Europe: Areas where it is the majority language Areas where it is a minority language or where it was the majority in the past Maltese Italian is the Italian language spoken in Malta. It has received some influences from the Maltese language. History Tri-lingual voting document for the later cancelled 1930 elections in Malta Enrico Mizzi (Prime Minister of Malta in 1950) was jailed in 1940 also for his pro-Italian la...

Saint Mark Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in Alexandria Religion in Egypt Religions in Egypt Islam Sunni Shia Christianity Coptic Orthodoxy Greek Orthodoxy Catholicism Protestantism Judaism Religious institutions Al-Azhar University Dar al-Ifta al-Misriyyah Coptic Orthodox Church Religious Organizations Al-Azhar Salafist Call Muslim Brotherhood al-Jama'a al-Islamiyya Catechetical School of Alexandria General Congregation Council Unrecognized religions & denominations Ahmadiyya Baháʼí Faith...

Eurovision Song Contest 1999Country GermanyNational selectionSelection processCountdown Grand Prix 1999Selection date(s)12 March 1999Selected entrantSürprizSelected songReise nach Jerusalem – Kudüs'e SeyahatSelected songwriter(s)Ralph SiegelBernd MeinungerFinals performanceFinal result3rd, 140 pointsGermany in the Eurovision Song Contest ◄1998 • 1999 • 2000► Germany participated in the Eurovision Song Contest 1999 with the song Reise nach Jerusa...