In Darkness (2011 film)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

KedsJenisAnak perusahaanIndustriPakaian olahraga dan peralatan olahragaDidirikan1916; 108 tahun lalu (1916)KantorpusatWaltham, Massachusetts, Amerika SerikatWilayah operasiSeluruh duniaTokohkunciGillian Meek, Presiden Blake Kruger, CEO Wolverine World WideProdukAlas kakiIndukWolverine World WideSitus webwww.keds.com Keds adalah sebuah merek sepatu kanvas dengan sol karet asal Amerika Serikat. Didirikan pada tahun 1916,[1] perusahaan ini dimiliki oleh Wolverine World Wide.[2&#...

The Jungle BookPoster film The Jungle BookSutradaraJon FavreauProduserJon FavreauBrigham TaylorDitulis olehJustin MarksBerdasarkanThe Jungle Bookoleh Rudyard KiplingPemeranNeel SethiBill MurrayBen KingsleyIdris ElbaLupita Nyong'oScarlett JohanssonChristopher WalkenGiancarlo EspositoNaratorBen KingsleyPenata musikJohn DebneySinematograferBill PopePenyuntingMark LivolsiPerusahaanproduksiWalt Disney PicturesFairview EntertainmentDistributorWalt Disney Studios Motion PicturesTanggal rilis 4...

العلاقات الأرجنتينية الفانواتية الأرجنتين فانواتو الأرجنتين فانواتو تعديل مصدري - تعديل العلاقات الأرجنتينية الفانواتية هي العلاقات الثنائية التي تجمع بين الأرجنتين وفانواتو.[1][2][3][4][5] مقارنة بين البلدين هذه مقارنة عامة ومرجعية لل�...

Helios Airways Penerbangan 522Ilustrasi pesawat 5B-DBY pada saat bertemu dengan F-16, Angkatan Udara Yunani di ketinggian 34000 ftRingkasan kecelakaanTanggal14 Agustus 2005RingkasanJatuh setelah ketidakmampuan kru karena kehilangan tekananLokasiGrammatiko, Marathon YunaniPenumpang115Awak6Cedera0Tewas121 (semua)Selamat0Jenis pesawatBoeing 737-31SNama pesawatOlympiaOperatorHelios AirwaysRegistrasi5B-DBYAsalBandar Udara Internasional LarnacaPerhentianBandar Udara Internasion...

Devoleena BhattacharjeeDevoleena Bhattacharjee saat acara promosi DilwaleLahir22 Agustus 1985 (umur 38)Sivasagar, Assam, IndiaKebangsaan IndiaPekerjaanAktrisPenari BharatnatyamModelTahun aktif2011–sekarangDikenal atasGopi Ahem Modi/Gopi Jaggi Modi (Saath Nibhaana Saathiya) Devoleena Bhattacharjee adalah seorang aktris India dan seorang penari Bharatnatyam yang terlatih.[1] Dia terkenal karena perannya sebagai Gopi Ahem Modi dalam program televisi Gopi. Dia adalah salah sa...

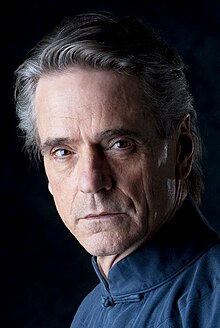

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento attori britannici non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Jeremy Irons nel 2015 Oscar al miglior attore 1991 Jeremy John Irons (AFI: [ˈdʒɛɹɪmi ˈaɪənz]; Cowes, 19 settembre 1948) è un attore e doppiatore britannico. Ha vinto il Premio Oscar al miglior a...

Twin-engine light utility helicopter AW169 AW169 at the Farnborough Air Show, 2012 Role HelicopterType of aircraft National origin Italy Manufacturer Leonardo S.p.A. AgustaWestland First flight 10 May 2012 Introduction 2015 Status Active service Produced 2015–present Number built 170+ as of October 2023 The AgustaWestland AW169[1] is a twin-engine, 10-seat, 4.8t helicopter developed and manufactured by the helicopter division of Leonardo (formerly AgustaWestland, merged into Finmecc...

Sébastien Roudet Roudet al Valenciennes nel novembre 2018 Nazionalità Francia Altezza 174 cm Peso 72 kg Calcio Ruolo Centrocampista Termine carriera 2021 Carriera Squadre di club1 1998-2004 Châteauroux156 (24)2004-2006 Nizza53 (4)2006-2008 Valenciennes60 (8)2008-2011 Lens80 (9)2011-2014 Sochaux81 (5)2014-2015 Châteauroux25 (2)2015-2019 Valenciennes95 (15)2020-2021Deolois3 (0) Nazionale 2001 Francia U-205 (0) 1 I due numeri indicano le presenze e l...

Artikel ini membutuhkan rujukan tambahan agar kualitasnya dapat dipastikan. Mohon bantu kami mengembangkan artikel ini dengan cara menambahkan rujukan ke sumber tepercaya. Pernyataan tak bersumber bisa saja dipertentangkan dan dihapus.Cari sumber: Sumitomo Chemical – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR (Juni 2018) Sumitomo Chemical Co., Ltd.Nama asli住友化学株式会社JenisPublik (K.K)Kode emitenTYO: 4005Komponen Nikkei 225DidirikanE...

Primary inlet of the Bosphorus in Istanbul, Turkey For other uses, see Golden Horn (disambiguation). For other uses, see Haliç (disambiguation). Map of Istanbul's Historic Peninsula (lower left), showing the location of the Golden Horn and Sarayburnu (Seraglio Point) in relation to Bosphorus strait, as well as historically significant sites (black), and various notable neighborhoods An aerial view of Galata (foreground), the Historic Peninsula (background), and the new Galata Bridge, which s...

ХристианствоБиблия Ветхий Завет Новый Завет Евангелие Десять заповедей Нагорная проповедь Апокрифы Бог, Троица Бог Отец Иисус Христос Святой Дух История христианства Апостолы Хронология христианства Раннее христианство Гностическое христианство Вселенские соборы Н...

1970 American film directed by John Waters Multiple ManiacsPromotional release posterDirected byJohn WatersWritten byJohn WatersProduced byJohn WatersStarring Divine David Lochary Mary Vivian Pearce Mink Stole Cookie Mueller Edith Massey George Figgs CinematographyJohn WatersEdited byJohn WatersMusic byJohn WatersProductioncompanyDreamlandDistributed byNew Line CinemaJanus Films (Restoration)Release date April 10, 1970 (1970-04-10) (Baltimore)[1] Running time96 minu...

بايزيد بن سليمان بن سليم (بالتركية: Şehzade Bayezid) منمنمة عثمانية تصور السلطان سليمان القانوني مع ابنه شاهزاده بايزيد. معلومات شخصية الميلاد 14 سبتمبر 1525الآستانة الدولة العثمانية الوفاة 23 أيلول 1561 (37 عام)قزوين الدولة الصفوية مكان الدفن سيواس مواطنة الدولة العثما�...

提示:此条目页的主题不是中華人民共和國最高領導人。 中华人民共和国 中华人民共和国政府与政治系列条目 执政党 中国共产党 党章、党旗党徽 主要负责人、领导核心 领导集体、民主集中制 意识形态、组织 以习近平同志为核心的党中央 两个维护、两个确立 全国代表大会 (二十大) 中央委员会 (二十届) 总书记:习近平 中央政治局 常务委员会 中央书记处 �...

منتخب روسيا لكأس فيد منتخب روسيا لكأس فيد البلد روسيا الكابتن إيغور أندريف تصنيف ITF 11 (12 November 2018) الألوان red & white كأس فيد أول سنة 1968 سنوات اللعب 43 Ties played (W–L) 137 (92–44) سنوات فيمجموعة العالم 33 (52–28) عدد مرات الفوز 4 (2004، 2005، 2007، 2008) المركز الثاني 7 (1988، 1990، 1999، 20012011، 2013، 2015) أكثر...

Universitas Yamanashi山梨大学 (Yamanashi Daigaku)bahasa Latin: Universitas YamanashiJenisNasionalDidirikan2002PresidenShinji Shimada[1]Staf administrasi1,451Jumlah mahasiswa4921Sarjana3876Magister925Doktor270LokasiKofu dan Tamaho, Yamanashi, JepangKampusKofu dan TamahoWarnaMerah anggurNama julukanNashidaiSitus webhttp://www.yamanashi.ac.jp/ Universitas Yamanashi (山梨大学code: ja is deprecated , Yamanashi Daigaku),[2] disingkat Nashidai (梨大code: ja is deprecate...

Scottish singer (born 1961) Susan BoyleBoyle in November 2009Background informationBirth nameSusan Magdalane Boyle[1][2][3]Born (1961-04-01) 1 April 1961 (age 63)[1]Dechmont, West Lothian, Scotland[4]OriginBlackburn, West Lothian, ScotlandGenresOperatic popOccupationsSingerYears active1998–presentLabels Sony Music Syco Columbia Websitesusanboylemusic.comMusical artist Susan Magdalane Boyle (born 1 April 1961)[1][5] is a Scottish s...

Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: John Bowes-Lyon – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR John Herbert Jock Bowes-Lyon (1 April 1886–7 Februari 1930) adalah putra kedua dari Pangeran Strathmore dan Kinghorne ke-14 dan Putri...

Marina LadyninaLahirMarina Alekseyevna Ladynina(1908-06-24)24 Juni 1908Skotinino, Smolensk, Kekaisaran RusiaMeninggal10 Maret 2003(2003-03-10) (umur 94)Moscow, Russian FederationMakamNovodevichy Cemetery, MoscowPekerjaanAktrisTahun aktif1929 - 1950anSuami/istriIvan PyryevPenghargaanStalin Prize (1941, 1942, 1926, 1948, 1951) People's Artist of the USSR (1950) Marina Alekseyevna Ladynina (bahasa Rusia: Мари́на Алексе́евна Лады́нина, 24 Juni 1908 &...

William PennL'ammiraglio sir William Penn dipinto da sir Peter LelyNascitaBristol, 23 aprile 1621 MorteLondra, 16 settembre 1670 Dati militariPaese servito Regno d'Inghilterra Arma Royal Navy Gradoammiraglio GuerreGuerra civile inglesePrima guerra anglo-olandeseSeconda guerra anglo-olandese Comandante diJamaica Station (Royal Navy) voci di militari presenti su Wikipedia Manuale William Penn (Bristol, 23 aprile 1621 – Londra, 16 settembre 1670) è stato un ammiraglio inglese, pa...