Hotel Marguery

|

Read other articles:

Strada statale 45di Val TrebbiaDenominazioni precedentiStrada nazionale 20 Strada nazionale 36 Strada nazionale 28 Strada nazionale 49 LocalizzazioneStato Italia Regioni Liguria Emilia-Romagna Province Genova Piacenza DatiClassificazioneStrada statale InizioGenova FinePiacenza Lunghezza118,859 km Provvedimento di istituzioneLegge 17 maggio 1928, n. 1094 GestoreANAS Manuale La strada statale 45 di Val Trebbia (SS 45) è una strada statale italiana che collega le citt�...

Indian spiritual leader (1907–2019) Shivakumara SwamiShivakumara Swami on 12 June 2007, aged 100BornShivanna(1907-04-01)1 April 1907Veerapur, Magadi, Kingdom of Mysore[1]Died(2019-01-21)21 January 2019(aged 111 years, 295 days)[2]Tumkur, Karnataka, IndiaOther namesSiddaganga Swamigalu, Nadedaduva Devaru, Kayaka Yogi, Trivida Daasohi, Abhinava Basavanna[3]EducationDoctor of Literature (honorary, 1965)OccupationsHumanitarianspiritual leadereducatorhead o...

Supermarket chain based in Puerto Rico Pueblo SupermarketsCompany typeGroceryIndustryRetailFounded1955HeadquartersSan Juan, Puerto RicoArea servedPuerto Rico and U.S. Virgin IslandsProductsBakery, dairy, deli, frozen foods, general grocery, meat, pharmacy, produce, seafood, snacks, liquorOwnerRamón CalderónDivisionsPueblo USVISubsidiariesAmigo SupermarketsWebsitehttps://puebloweb.com Pueblo is a Puerto Rican supermarkets chain. It has been one of Puerto Rico's major supermarket chains since...

Sidewheel steamer ram ship For the 1995 sternwheeler, see Queen of the West (ship). USS Queen of the West History United States NameUSS Queen of the West Launched1854 Commissioned1862 FateCaptured by Confederate States Army, February 14, 1863 Confederate States NameCSS Queen of the West CommissionedFebruary 1863 FateAttacked and destroyed, April 11, 1863 General characteristics TypeSidewheel steamer Displacement406 tons[1] Length180 ft (55 m) Beam37 ft 6 in (11.43&...

Синелобый амазон Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:ЗавропсидыКласс:Пт�...

The location of Monaco (dark green, in circle) in Europe Part of a series onJews and Judaism Etymology Who is a Jew? Religion God in Judaism (names) Principles of faith Mitzvot (613) Halakha Shabbat Holidays Prayer Tzedakah Land of Israel Brit Bar and bat mitzvah Marriage Bereavement Baal teshuva Philosophy Ethics Kabbalah Customs Rites Synagogue Rabbi Texts Tanakh Torah Nevi'im Ketuvim Talmud Mishnah Gemara Rabbinic Midrash Tosefta Targum Beit Yosef Mishneh Torah Tur Shu...

Călin Constantin Anton Popescu-Tăriceanu Perdana Menteri RumaniaMasa jabatan29 Desember 2004 – 22 Desember 2008PresidenTraian BăsescuNicolae Văcăroiu (sementara)Traian BăsescuPendahuluEugen Bejinariu (sementara) Adrian NăstasePenggantiEmil BocPemimpin Partai Liberal Nasional pada Kamar DeputiPetahanaMulai menjabat 15 Desember 2008PendahuluCrin AntonescuPenggantiPetahanaMenteri Luar NegeriMasa jabatan21 Maret 2007 – 5 April 2007PendahuluMihai-Răzvan UngureanuP...

College baseball team in the 2022 NCAA Division I season 2022 Oregon State Beavers baseballCorvallis Regional championsCorvallis Super Regional, 1—2ConferencePac-12 ConferenceRankingCoachesNo. 2CBNo. 5Record48–18 (20–10 Pac-12)Head coachMitch Canham (3rd season)Assistant coaches Darwin Barney (2nd season) Ryan Gipson (4th season) Pitching coachRich Dorman (3rd season)Home stadiumGoss Stadium at Coleman FieldSeasons← 20212023 → 2022 Pac-12 ...

Divizia A 1970-1971 Competizione Liga I Sport Calcio Edizione 53ª Organizzatore FRF Date dal 30 agosto 1970al 27 giugno 1971 Luogo Romania Partecipanti 16 Risultati Vincitore Dinamo București(6º titolo) Retrocessioni Progresul BucureștiCFR Timișoara Statistiche Miglior marcatore Florea Dumitrache Constantin Moldoveanu Gheorghe Tătaru (15) Cronologia della competizione 1969-1970 1971-1972 Manuale La Divizia A 1970-1961 è stata la 53ª edizione della massima serie del...

Сельское поселение России (МО 2-го уровня)Новотитаровское сельское поселение Флаг[d] Герб 45°14′09″ с. ш. 38°58′16″ в. д.HGЯO Страна Россия Субъект РФ Краснодарский край Район Динской Включает 4 населённых пункта Адм. центр Новотитаровская Глава сельского пос�...

Hong Kong actor, filmmaker and racing driver For the Episcopal priest, see Daniel G. C. Wu. For the American soccer player, see Daniel Wu (soccer). In this Chinese name, the family name is Wu. Daniel WuWu at the 2015 San Diego Comic-Con InternationalBornDaniel N Wu[1] (1974-09-30) September 30, 1974 (age 49)Berkeley, California, U.S.Alma materUniversity of OregonOccupation(s)Actor, director, producer, screenwriterYears active1998–presentSpouse Lisa S. (...

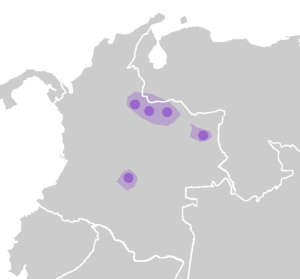

Macro-Arawakan language family spoken in Colombia GuajibanWahívoan, GuajiboanGeographicdistributionColombian and Venezuelan LlanosLinguistic classificationMacro-Arawakan (?)GuajibanGlottologguah1252 Guajiboan (also Guahiban, Wahívoan, Guahiboan) is a language family spoken in the Orinoco River region in eastern Colombia and southwestern Venezuela, a savanna region known as the Llanos. Family division Guajiboan consists of 5 languages: Guajiboan Macaguane (also known as Hitnü, Macaguán, Ma...

Historic church in California, United States United States historic placeSt. Joseph's Church and ComplexU.S. National Register of Historic PlacesSan Francisco Designated Landmark No. 120 Show map of San Francisco CountyShow map of CaliforniaShow map of the United StatesLocation1401–1415 Howard St., San Francisco, CaliforniaCoordinates37°46′25″N 122°24′47″W / 37.77361°N 122.41306°W / 37.77361; -122.41306Area1.4 acres (0.57 ha)Built1914 ...

Carlos Federico Príncipe de Hohenzollern-SigmaringenReinado 1769-1785Información personalNacimiento 9 de enero de 1724SigmaringenFallecimiento 20 de diciembre de 1785KrauchenwiesReligión CatolicismoFamiliaDinastía Hohenzollern-SigmaringenPadre Príncipe José Federico ErnestoMadre María Francisca Luisa de Oettingen-SpielbergConsorte Juana de Hohenzollern-Bergh[editar datos en Wikidata] Carlos Federico (9 de enero de 1724 - 20 de diciembre de 1785) fue un miembro de la Casa de H...

Irish republican Bobby StoreyStorey in 2012Born(1956-04-11)11 April 1956Belfast, Northern IrelandDied21 June 2020(2020-06-21) (aged 64)Newcastle upon Tyne, England[1]Political partySinn Féin Robert Storey (11 April 1956 – 21 June 2020)[2][3] was a Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) volunteer from Belfast, Northern Ireland. Prior to an 18-year conviction for possessing a rifle, he also spent time on remand for a variety of charges and in total served 20 yea...

Historic house in New Jersey United States historic placeNothnagle, C. A., Log HouseU.S. National Register of Historic PlacesNew Jersey Register of Historic Places Show map of Gloucester County, New JerseyShow map of New JerseyShow map of the United StatesLocationSwedesboro-Paulsboro Road, Gibbstown, New JerseyCoordinates39°49′5″N 75°15′59″W / 39.81806°N 75.26639°W / 39.81806; -75.26639Area1.5 acres (0.61 ha)Builtsome parts 1638–1643; the remainder c...

MIUI 開発者 XiaomiOSの系統 Unix系, Linux, Android開発状況 開発終了ソースモデル プロプライエタリソフトウェア初版 0.8.16 / 2010年8月16日 (14年前) (2010-08-16)最新安定版 14 / 2022年12月11日 (21か月前) (2022-12-11)パッケージ管理 Google Play (中国を除く)APK既定のUI GUIライセンス GNU General Public License v3Apache License 2.0後続品 Xiaomi HyperOSウェブサイト home.miui.com(中国語)en.miui.com�...

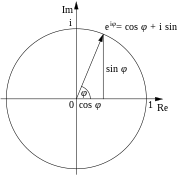

Logarithm to the base of the mathematical constant e Base e redirects here. For the numbering system which uses e as its base, see Non-integer base of numeration § Base e. Natural logarithmGraph of part of the natural logarithm function. The function slowly grows to positive infinity as x increases, and slowly goes to negative infinity as x approaches 0 (slowly as compared to any power law of x).General informationGeneral definition ln x = log e x {\displaystyle \ln x=...

Faint solar glow caused by interplanetary dust at sunset and sunrise Parts of this article (those related to the hypothesized origin of the zodiacal cloud - Mars dust, rather than comets or asteroids) need to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (March 2021) Two false dawns,[1] gegenschein (middle) and the rest of the zodiacal band of light and zodiac marked (visually crossed by the Milky Way), in this composite image of ...

American poet and writer (1926–1997) For the American businessman, see Alan Ginsburg. For the serial killer who was born Allen Ginsberg, see William MacDonald (serial killer). Allen GinsbergGinsberg in 1979BornIrwin Allen Ginsberg(1926-06-03)June 3, 1926Newark, New Jersey, U.S.DiedApril 5, 1997(1997-04-05) (aged 70)New York City, U.S.OccupationWriter, poetEducationMontclair State UniversityColumbia University (BA)University of California, BerkeleyLiterary movementBeat literatureConfess...