Hong Gildong jeon

| |||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Longjumeau (homonymie). Longjumeau Le parc Nativelle. Blason Logo Administration Pays France Région Île-de-France Département Essonne Arrondissement Palaiseau Intercommunalité Communauté d'agglomération Paris-Saclay Maire Mandat Sandrine Gelot (LR) 2020-2026 Code postal 91160 Code commune 91345 Démographie Gentilé Longjumellois Populationmunicipale 20 620 hab. (2021 ) Densité 4 260 hab./km2 Géographie Coordonnées 48° 41�...

Disambiguazione – Se stai cercando altri significati, vedi 1945 (disambigua). XIX secolo · XX secolo · XXI secolo Anni 1920 · Anni 1930 · Anni 1940 · Anni 1950 · Anni 1960 1941 · 1942 · 1943 · 1944 · 1945 · 1946 · 1947 · 1948 · 1949 Il 1945 (MCMXLV in numeri romani) è un anno del XX secolo. 1945 negli altri calendari Calendario gregoriano 1945 Ab Urbe condita 2698 (MMDCXCVIII) Calendario armen...

العلاقات الإسرائيلية البوتسوانية إسرائيل بوتسوانا تعديل مصدري - تعديل العلاقات الإسرائيلية البوتسوانية هي العلاقات الثنائية بين إسرائيل وبوتسوانا. لدى البلدان علاقات رسمية ولكن دون وجود سفارات أو قنصليات رسمية في عاصمتهما، وقد توصل البلدان إلى عدد من ا...

Suasana Jalan Fatmawati saat pembangunan MRT Jakarta pada 31 Juli 2017 Kedatangan kereta Ratangga MRT Jakarta di Stasiun MRT Cipete Raya yang terletak di Jalan Fatmawati Jalan Fatmawati atau Jalan RS Fatmawati Raya adalah nama salah satu jalan utama Jakarta. Nama jalan ini diambil dari nama salah satu istri Presiden pertama Indonesia, Soekarno dan pahlawan nasional Indonesia, yaitu Fatmawati. Jalan ini membentang sepanjang 5,4 KM dari Pondok Labu, Cilandak, Jakarta Selatan sampai Pulo, Kebayo...

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (December 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) 20th Operations GroupEmblem of the 20th Operations GroupActive1930–1945; 1946–1955; 1992–presentCountryUnited StatesBranchUnited States Air ForceMilitary unit General Dynamics F-16CJ Block 50D (91-0380) of the 55th Fighter Squadron returns...

American television drama series, 2011–2012 Pan AmGenre Period drama Historical fiction Created byJack OrmanDeveloped byNancy Hult GanisStarring Christina Ricci Margot Robbie Michael Mosley Karine Vanasse Mike Vogel Kelli Garner ComposerBlake NeelyCountry of originUnited StatesOriginal languageEnglishNo. of seasons1No. of episodes14ProductionExecutive producers Nancy Hult Ganis Jack Orman Thomas Schlamme Steven Maeda[1] Sid Ganis Producers Rebecca Moline Marta Gene Camps Toby Conroy...

English physicist For other people named Henry Moseley, see Henry Moseley (disambiguation). Henry MoseleyMoseley in 1914BornHenry Gwyn Jeffreys Moseley(1887-11-23)23 November 1887Weymouth, Dorset, EnglandDied10 August 1915(1915-08-10) (aged 27)Gallipoli, Ottoman EmpireCause of deathKilled in actionEducationSummer Fields SchoolEton CollegeAlma materTrinity College, OxfordUniversity of ManchesterKnown forAtomic number, Moseley's lawAwardsMatteucci Medal (1919)Scientific care...

Proposed NASA Mars communications satellite Not to be confused with the Earth Return Orbiter, an ESA Mars orbiter. Next Mars OrbiterThis proposed telecommunications orbiter features ion thrusters and improved solar arrays.NamesNeMO, Mars 2022 orbiter[1]Mission typeTelecommunications and reconnaissanceOperatorNASAMission durationPlanned: 6.5 years[1] Spacecraft propertiesLaunch mass1,900 kg (4,200 lb)[1]Dry mass1,300 kg (2,900 lb)[1]Payload m...

Liturgical vestment This article is about the liturgical garment. For the Roman military formation, see Maniple (military unit). A maniple The maniple is a liturgical vestment used primarily within the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church, and occasionally used by some Anglo-Catholic and Lutheran clergy. It is an embroidered band of silk or similar fabric that is hung over the left arm. It is only used within the context of the Mass, and it is of the same liturgical colour as the other Mass vest...

Get Your WingsAlbum studio karya AerosmithDirilisMaret 1974DirekamDesember 1973 - Januari 1974 pada Record Plant Studios, New YorkGenreHard rockDurasi38:04LabelColumbiaProduserRay Colcord, Jack DouglasKronologi Aerosmith Aerosmith(1973)Aerosmith1973 Get Your Wings(1974) Toys in the Attic(1975)Toys in the Attic1975 Get Your Wings Adalah album kedua dari grup musik rock asal Amerika Aerosmith yang dirilis pada tahun 1974. Daftar lagu Same Old Song and Dance (Steven Tyler, Joe Perry) – 3:5...

Cadole en pierre sèche à Lugny, en Haut-Mâconnais (photo prise en 2004). « Cadole » est le nom donné aux anciennes cabanes, souvent en pierres sèches, des vignobles de l'Aube et de Bourgogne du Sud, et plus particulièrement du Beaujolais. Variantes du mot Le terme cadole, issu du patois lyonnais[1], s'écrit aussi cadolle. On trouve également la variante cadeule, ainsi à Martailly-lès-Brancion (Saône-et-Loire)[2]. Aire d'extension du mot Pris dans le sens de « caba...

Chemical compound Not to be confused with Dimethylstilbestrol. DimestrolClinical dataTrade namesDepot-Ostromon; Depot-Oestromon; Depot-Cyren; SynthilaOther namesDianisylhexene; 4,4'-Dimethoxy-α,α'-diethylstilbene; Diethylstilbestrol dimethyl ether; Dimethoxydiethylstilbestrol; (E)-4,4'-(1,2-Diethylethylene)dianisoleDrug classNonsteroidal estrogen; Estrogen etherIdentifiers IUPAC name 1-methoxy-4-[(E)-4-(4-methoxyphenyl)hex-3-en-3-yl]benzene CAS Number130-79-0PubChem CID3032539ChemSpider2297...

English cricketer & rugby union player Maurice TurnbullPersonal informationFull nameMaurice Joseph Lawson TurnbullBorn16 March 1906Cardiff, WalesDied5 August 1944(1944-08-05) (aged 38)Montchamp, German-occupied FranceBattingRight-handedBowlingRight-arm offbreakInternational information National sideEnglandTest debut10 January 1930 v New ZealandLast Test27 June 1936 v India Career statistics Competition Test First-class Matches 9 388 Runs scored 224 17,544 Bat...

Частина серії проФілософіяLeft to right: Plato, Kant, Nietzsche, Buddha, Confucius, AverroesПлатонКантНіцшеБуддаКонфуційАверроес Філософи Епістемологи Естетики Етики Логіки Метафізики Соціально-політичні філософи Традиції Аналітична Арістотелівська Африканська Близькосхідна іранська Буддій�...

Alex Telles Telles with Manchester United in 2021Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Alex Nicolao Telles[1]Tanggal lahir 15 Desember 1992 (umur 31)[2]Tempat lahir Caxias do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul, BrazilTinggi 181 m (593 ft 10 in)[2]Posisi bermain Left-backInformasi klubKlub saat ini Al NassrKarier junior2007–2011 JuventudeKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2011–2012 Juventude 28 (2)2013–2014 Grêmio 42 (1)2014–2016 Galatasaray 39 (2)2015–2016...

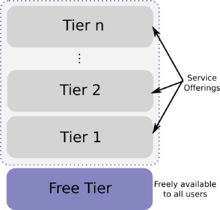

Freemium[1][2] adalah sebuah model bisnis dengan penawaran layanan mendasar secara cuma-cuma tetapi mengenakan biaya untuk fitur khusus atau lanjutan yang disebut premium. Kata freemium merupakan lakuran yang dibuat dengan mengombinasikan dua aspek dari model bisnis ini, yaitu free dan premium. Model bisnis ini populer di kalangan perusahaan Web 2.0.[3] Asal-usul Model bisnis freemium telah digunakan oleh perusahaan perangkat lunak sejak 1980-an. Layanan sering kali di...

Japanese supernatural entity Sokokuradani no Akaname (Akaname of the Deep Dark Valley), a frame on a picture print used as dice game board. Hyakushu kaibutsu yōkai sugoroku (1858) by Utagawa Yoshikazu [ja]. Akaname, Gazu hyakkiyagyō by Toriyama Sekien[1] The akaname (垢(あか)嘗(なめ), 'scum-licker'; 'filth-licker') is a Japanese yōkai depicted in Toriyama Sekien's 1776 book Gazu Hyakki Yagyō,[2][3] with its precursor or equivalent akaneburi (/垢...

Public college in Alfred, New York, US Not to be confused with Alfred University. This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Alfred State College – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Alfred State CollegeFormer namesNew York State Schoo...

Athletics at the1979 Summer UniversiadeTrack events100 mmenwomen200 mmenwomen400 mmenwomen800 mmenwomen1500 mmenwomen5000 mmen10,000 mmen100 m hurdleswomen110 m hurdlesmen400 m hurdlesmen3000 msteeplechasemen4×100 m relaymenwomen4×400 m relaymenField eventsHigh jumpmenwomenPole vaultmenLong jumpmenwomenTriple jumpmenShot putmenwomenDiscus throwmenwomenHammer throwmenJavelin throwmenwomenCombined eventsPentathlonwomenDecathlonmenvte The men's 400 metres event at the 1979 Summer Universiade ...

41°48′22″N 12°19′35″E / 41.806179°N 12.326409°E / 41.806179; 12.326409 RomicsStands during Romics 2012StatusactiveGenreComics, Animation, Games, Movies, Role-playing games, EntertainmentDate(s)April (spring edition) and October (autumn edition)VenueFiera di RomaLocation(s)RomeCountryItalyInaugurated2001Attendance400,000[1]Organized byFiera di Roma, Castelli AnimatiWebsiteromics.it Romics is an international semiannual comic book, animation, and gami...