Diyari

|

Read other articles:

Nusa Tenggara Timur FlobamoraProvinsiDari atas ke bawah; kiri ke kanan: Komodo, Pulau Padar, Kampung Adat Praijing Sumba, Alat Musik Sasando, Gunung Kelimutu, Tari Caci, dan Pantai Walakiri Sumba Timur. BenderaLambangPetaNegara IndonesiaDasar hukum pendirianUU Nomor 64 Tahun 1958(11 Agustus 1958)[1]Tanggal20 Desember 1958 (umur 65)Ibu kotaKota KupangJumlah satuan pemerintahan Daftar Kabupaten: 21Kota: 1Kecamatan: 309Kelurahan: 327Desa: 3026 Pemerintahan • Gubernu...

1985 song by the Smiths For the TV series, see How Soon Is Now? (TV series). How Soon Is Now?Single by the Smithsfrom the album Hatful of Hollow B-sideWell I WonderOscillate WildlyReleased28 January 1985 (1985-01-28)RecordedJuly 1984StudioJam, LondonGenreAlternative rock[1]psychedelia[2]Length6:44LabelRough TradeSongwriter(s)Johnny MarrMorrisseyProducer(s)John PorterThe Smiths singles chronology William, It Was Really Nothing (1984) How Soon Is Now? (1985) Shake...

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Westinghouse Rail Systems – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Westinghouse Rail Systems LtdFormerlyWestinghouse SignalsCompany typeSubsidiaryIndustryTransportFounded1900Defunct2013&...

Markos Informasi pribadiLahir15 Maret 1966 (umur 58)Pagar Alam, Sumatera SelatanKebangsaanIndonesiaSuami/istriLetkol Laut (K/W) Ninuk Fitri HandayaniAnakMarfi PasmahAndina LauraRonald PasmahAlma materAkademi Angkatan Laut (1989)Karier militerPihak IndonesiaDinas/cabang TNI Angkatan LautMasa dinas1989—sekarangPangkat Mayor Jenderal TNI (Mar)NRP9652/PSatuanKorps MarinirPertempuran/perangOperasi SerojaSunting kotak info • L • B Mayor Jenderal TNI (Mar) (Purn.) Mark...

Space suit technology demonstrator The Mark III suit worn by NASA geologist Dean Eppler during field testing at Meteor Crater near Winslow, Arizona, US The Mark III or MK III (H-1) is a NASA space suit technology demonstrator built by ILC Dover. While heavier than other suits (at 59 kilograms (130 lb), with a 15 kilograms (33 lb) Primary Life Support System backpack), the Mark III is more mobile, and is designed for a relatively high operating pressure.[1] The Mark III is a ...

Castle in Kashmar, Iran Atashgah Castleقلعه آتشگاهAtashgah Castle is one of the castles in IranAtashgah CastleLocation within IranGeneral informationStatusRuinedTypeCastleArchitectural styleSasanianTown or cityKashmarCountryIranCoordinates35°18′59″N 58°23′10″E / 35.31639°N 58.38611°E / 35.31639; 58.38611Technical detailsStructural systemDefensive Atashgah Castle (Persian: قلعه آتشگاه) is a castle in the city of Kashmar, and is one of the...

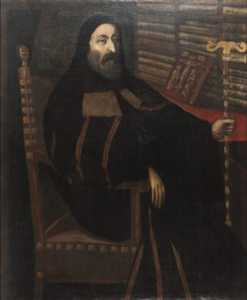

Gabriele Severovescovo della Chiesa greca ortodossa Incarichi ricopertimetropolita, esarca patriarcale per Venezia e la Dalmazia Manuale Gabriele Severo, italianizzazione di Gavriīl Sevīros (in greco Γαβριήλ Σεβήρος?; Malvasia, 1541 – Lesina, 21 ottobre 1616), è stato un vescovo ortodosso e teologo greco, noto per aver utilizzato le categorie e la terminologia della filosofia scolastica nella teologia ortodossa.[1]. Indice 1 Biografia 2 Opere ...

Peta Lokasi Kabupaten Labuhanbatu Utara di Sumatera Utara Berikut adalah daftar kecamatan dan kelurahan di Kabupaten Labuhanbatu Utara.Kabupaten Labuhanbatu Utara terdiri dari 8 kecamatan, 8 kelurahan, dan 82 desa dengan luas wilayah mencapai 3.545,80 km² dan jumlah penduduk sekitar 381.994 jiwa (2020) dengan kepadatan penduduk 108 jiwa/km².[1][2] Daftar kecamatan dan kelurahan di Kabupaten Labuhanbatu Utara, adalah sebagai berikut: Kode Kemendagri Kecamatan Jumlah Kelurahan...

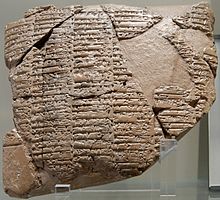

Script used to write the Elamite language Elamite cuneiformInscription of Shutruk-Nahhunte in Elamite cuneiform on the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin.Script type Logogram Time period3000 BCE to 400 BCELanguagesElamite languageRelated scriptsParent systemsSumerian cuneiformAkkadian cuneiformElamite cuneiformSister systemsOld Persian cuneiform This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA.&...

Dam in FranceMalpasset DamThe ruins of the dam 2014Location of Malpasset Dam in FranceOfficial nameFrench: Barrage de MalpassetLocationFranceCoordinates43°30′43.48″N 6°45′23.40″E / 43.5120778°N 6.7565000°E / 43.5120778; 6.7565000Construction beganApril 1952Opening date1954Demolition date2 December 1959Construction cost580 million francs (by 1955 prices)Designed byAndré CoyneOwner(s)Département Var (59)Dam and spillwaysType of ...

Statue of the patron deity of the ancient city of Babylon The Statue of Marduk depicted as being mounted on Marduk's dragon Mušḫuššu and standing victorious in the primordial water of Tiamat. From a cylinder seal of the 9th century BC Babylonian king Marduk-zakir-shumi I.[1] The Statue of Marduk, also known as the Statue of Bêl (Bêl, meaning lord, being a common designation for Marduk),[2] was the physical representation of the god Marduk, the patron deity of the ancien...

SMK Negeri 1 Teluk MengkuduSekolah Menengah Kejuruan Negeri 1 Teluk MengkuduInformasiDidirikanJuli 2012JenisNegeriAkreditasiCNomor Statistik Sekolah69728741Kepala SekolahRoslina Tanjung, M.Pd.Jumlah kelas17 rombelJurusan atau peminatanTKJ, TKRO, OTKP, dan APATKurikulumKurikulum 2013Jumlah siswa580AlamatLokasiJalan Pekan Sialang Buah, Kecamatan Teluk Mengkudu, Serdang Bedagai, Sumatera Utara, IndonesiaSitus webhttps://smkn1tm.sch.idLain-lainLulusanIKATEMENGMotoMotoCreativit...

49th quadrennial U.S. presidential election 1980 United States presidential election ← 1976 November 4, 1980 1984 → 538 members of the Electoral College270 electoral votes needed to winTurnout54.2%[1] 0.6 pp Nominee Ronald Reagan Jimmy Carter John B. Anderson Party Republican Democratic Independent[a] Home state California Georgia Illinois Running mate George H. W. Bush Walter Mondale Patrick Lucey Electoral vote 489 49 0 States ...

Thomas VinterbergThomas Vinterberg pada Februari 2010Lahir19 Mei 1969 (umur 55)Copenhagen, DenmarkPekerjaanSutradara, produser, penulis latar dan pemeranSuami/istriMaria Walbom (1990–2007) Thomas Vinterberg (lahir 19 Mei 1969) adalah seorang sutradara Denmark yang, bersama dengan Lars von Trier, membentuk gerakan Dogme 95 dalam bidang pembuatan film, yang mendirikan peraturan-peraturan untuk menyederhanakan produksi film. Kehidupan dan karier Vinterberg lahir di Copenhagen, Denmark. P...

Psychological effect This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. (January 2021) The frog pond effect is the theory that individuals evaluate themselves as worse than they actually are when in a group of higher-performing individuals.[1][2] This effect is a part of the wider social comparison theory. It relates to how individuals...

Artikel ini membutuhkan rujukan tambahan agar kualitasnya dapat dipastikan. Mohon bantu kami mengembangkan artikel ini dengan cara menambahkan rujukan ke sumber tepercaya. Pernyataan tak bersumber bisa saja dipertentangkan dan dihapus.Cari sumber: Kawasan Industri Wijayakusuma – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR (Maret 2016) PT Kawasan Industri WijayakusumaSebelumnyaPT Kawasan Industri CilacapJenisPerseroan terbatasIndustriKawasan indus...

Men's scratch at the 2018 UEC European Track ChampionshipsVenueSir Chris Hoy Velodrome, GlasgowDate3 AugustCompetitors22 from 22 nationsMedalists Roman Gladysh Ukraine Adrien Garel France Tristan Marguet Switzerland← 20172019 → 2018 UEC EuropeanTrack ChampionshipsSprintmenwomenTeam sprintmenwomenTeam pursuitmenwomenKeirinmenwomenOmniummenwomenMadisonmenwomenTime trialmenwomenIndividual pursuit...

Eddy Achir Informasi pribadiLahir1929Garut, Jawa BaratMeninggal30 November 2008 (usia 78 atau 79 tahun)Karier militerDinas/cabang TNI Angkatan DaratMasa dinas? – 1985Pangkat Mayor Jenderal TNINRP14134SatuanArtileri (Art.)Sunting kotak info • L • B Mayor Jenderal TNI (Purn.) Eddy Mohammad Achir (1929 – 30 November 2008) merupakan seorang perwira tinggi Angkatan Darat. Pendidikan Kursus Singkat, Angkatan II, Seskoad (1967)[1] Jabatan mili...

Ollioules L'église Saint-Laurent. Blason Administration Pays France Région Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur Département Var Arrondissement Toulon Intercommunalité Métropole Toulon Provence Méditerranée Maire Mandat Robert Beneventi 2020-2026 Code postal 83190 Code commune 83090 Démographie Gentilé Ollioulais Populationmunicipale 14 011 hab. (2021 ) Densité 704 hab./km2 Géographie Coordonnées 43° 07′ 59″ nord, 5° 51′ 00″ est Alti...

American politician (1841–1912) Henry Harrison BinghamHenry Harrison BinghamBorn(1841-12-04)December 4, 1841Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.DiedMarch 22, 1912(1912-03-22) (aged 70)Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.Place of burialLaurel Hill CemeteryPhiladelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.AllegianceUnited StatesUnionService/branchUnited States ArmyUnion ArmyYears of service1862–1866Rank Major Brevet Brigadier GeneralUnit 140th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer InfantryBattles/wars American C...